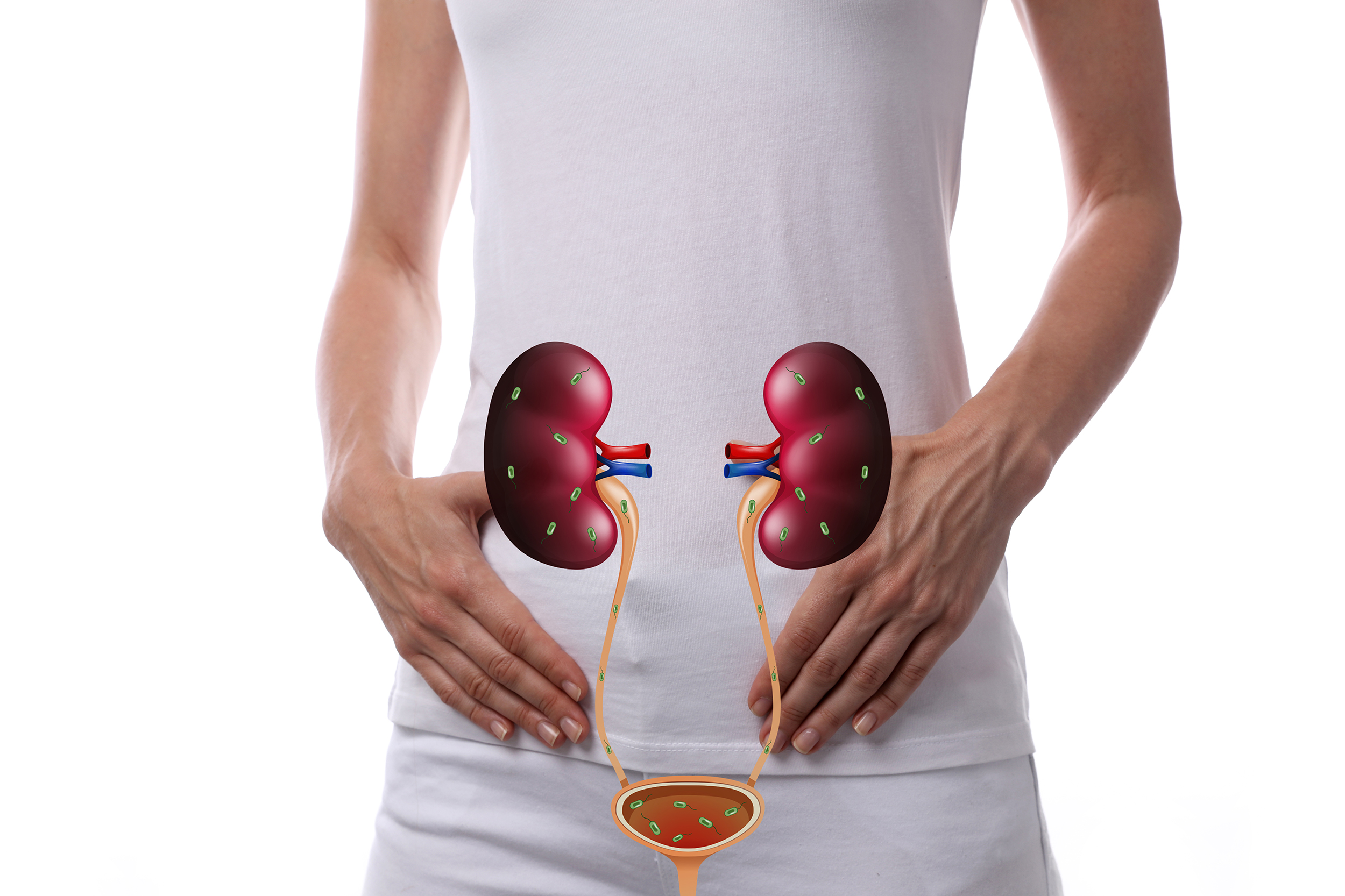

Interstitial cystitis- “evil twin” of endometriosis

Last week, we noted that adenomyosis can frequently coexist in people with endometriosis. Another one of those conditions that can frequently coexist with endometriosis, aptly named the “evil twin” to endometriosis, is interstitial cystitis (IC) (also called painful bladder syndrome). The walls of the bladder become inflamed or irritated, resulting in symptoms similar to a bladder infection, such as urinary urgency and/or frequency, painful urination, and pelvic pain (Al-Shaiji et al., 2021). However, in IC, there is no infection, and the symptoms can often be exacerbated during the time around menses (Al-Shaiji et al., 2021).

Endometriosis and IC can both be found in 80% of people with chronic pelvic pain (Al-Shaiji et al., 2021). Like endometriosis, it can take several years for a diagnosis of IC to be made (Al-Shaiji et al., 2021). It is important to consider this condition when looking at treatments for chronic pelvic pain. Al-Shaiji et al. (2021) reports that “up to 25%–40% of patients who undergo hysterectomy as a treatment of CPP will continue to have pain postoperatively.” Al-Shaiji et al. (2021) also cites another study that discovered that “IC was found in 79% of the patients” who had persistent pelvic pain after a hysterectomy (who were subsequently treated for IC and had improvements in their symptoms). Al-Shaiji et al. (2021) concluded that it is important to look beyond endometriosis as the only cause of a person’s pelvic pain, especially if previous treatments have been ineffective.

For more information on IC, see: https://icarebetter.com/interstitial-cystitis_bladder-pain-syndrome-by-susan-pierce-richards/

Reference

Al-Shaiji, T. F., Alshammaa, D. H., Al-Mansouri, M. M., & Al-Terki, A. E. (2021). Association of endometriosis with interstitial cystitis in chronic pelvic pain syndrome: Short narrative on prevalence, diagnostic limitations, and clinical implications. Qatar Medical Journal, 2021(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.5339/qmj.2021.50

Adenomyosis- sister to endometriosis

Endometriosis is often found along with other conditions that can cause similar symptoms (see Related Conditions). One of those conditions is called adenomyosis, where endometrial glands and stroma invade the muscular part of the uterine wall (Gracia et al., 2022). Vannuccini and Petraglia (2019) report that “adenomyosis and endometriosis share a number of features, so that for many years adenomyosis has been called endometriosis interna,” but the authors go on to point out that “nevertheless, they are considered two different entities.” Adenomyosis is found in those with endometriosis anywhere from 20-80% of the time (Vannuccini & Petraglia, 2019)!

Both conditions share similar symptoms, such as painful periods and abnormal uterine bleeding. This is important to keep in mind when looking at treatment options as it has been seen that “after surgical treatment…pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) were significantly more likely to persist with the presence of adenomyosis” (Gracia et al., 2022). Vannuccini and Petraglia (2019) also found this- noting that “on ultrasound pre-operative assessment, 47.8% of patients undergoing surgery for [deep infiltrating endometriosis] were affected by adenomyosis, and in those affected by both conditions, the surgical treatment was not as effective in treating pain as it was in those with only endometriosis.” The ability to diagnose adenomyosis with magnetic resonance imaging and/or transvaginal ultrasound (versus only after a hysterectomy) has made it easier to plan prior to surgery and adjust expectations.

When looking at treating chronic pelvic pain, it is important to note that endometriosis often coexists with several other conditions that can cause similar symptoms. These other conditions, if left untreated, can continue to cause symptoms, which can lead to a great deal of discouragement if you are not aware.

For more information on adenomyosis, see: https://icarebetter.com/adenomyosis/

References

Vannuccini, S., & Petraglia, F. (2019). Recent advances in understanding and managing adenomyosis. F1000Research, 8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6419978/

Loring, M., Chen, T. Y., & Isaacson, K. B. (2021). A Systematic review of adenomyosis: It is time to reassess what we thought we knew about the disease. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology, 28(3), 644-655. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1553465020311006

Gracia, M., de Guirior, C., Valdés-Bango, M., Rius, M., Ros, C., Matas, I., … & Carmona, F. (2022). Adenomyosis is an independent risk factor for complications in deep endometriosis laparoscopic surgery. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1-8. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-11179-8

Teens with endometriosis

Endometriosis in adolescents was recently reviewed by Liakopoulou et al. (2022), and they report that “adolescent endometriosis is a challenging diagnosis” and that “the disease can be easily overlooked”- thus the true incidence of endometriosis in teens is not really known. The diagnosis in teens is often delayed which “can lead to suffering for several years.” The authors state that “consequently, early diagnosis appears to be of upmost importance, especially as far as adolescents and young patients are concerned, as it can optimize life quality, relief symptomatology, and decrease the negative impact of the disease on future fertility.”

To achieve earlier diagnosis, the authors suggest that “further evaluation should be considered when prolonged use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is reported by the patient, there are relatives diagnosed with endometriosis (in cases of frequent absenteeism from everyday activities during menstruation), and estroprogestin contraceptives have been prescribed before the age of 18 years for primary dysmenorrhea treatment.” They report that “ACOG recommends laparoscopy for diagnosing endometriosis in adolescents” and that “diagnostic laparoscopy is indicated if there is no relief after 3–6 months of medical management.” The authors do report that ultrasounds and MRI’s may be utilized, but that normal imaging doesn’t rule out endometriosis. The authors state that “the benefits of laparoscopy do not only include the confirmation of diagnosis, but also the opportunity of intraoperative treatment.” But the ability to identify endometriosis is important as “during laparoscopy, endometriosis may have a variable appearance.” In adolescents, they report that “white, yellow-brown, red-pink lesions, as well as clear shiny vesicular lesions, are more frequent” and are “associated with greater levels of pain.” The authors also advise that “if suspicious lesions are not identified during laparoscopy, random biopsies of the cul-de-sac should be obtained.” The authors also remind us that “most adolescents present with stage I–II disease; however, advanced stage III–IV disease, including ovarian endometriomas, is increasingly diagnosed in adolescents” and that “the stage and location of the lesions do not directly corelate with the severity or frequency of symptoms.”

The authors note that to help with symptom relief “continuous hormonal therapy can be used to suppress menstruation and is considered safe.” But they report that the use of “gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist or antagonist is not recommended in adolescents with chronic pelvic pain and suspected endometriosis, due to potential impact on bone density.” If GnRH agonists are used, they state that the use “cannot exceed short periods of time, as long-term use may lead to bone density loss and potentially affect negatively cardiovascular risk.” They also caution that “GnRH agonists, when administered before surgery, change the macroscopic image of endometriotic lesions, make their visualization harder, and, thus, preclude effective surgical treatment.” They also state that “depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) use is limited, due its association with lower bone mineral density” as well.

Reference

Liakopoulou, M. K., Tsarna, E., Eleftheriades, A., Arapaki, A., Toutoudaki, K., & Christopoulos, P. (2022). Medical and Behavioral Aspects of Adolescent Endometriosis: A Review of the Literature. Children, 9(3), 384. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/9/3/384/htm

Endometriosis and early menopause

Is there an association between endometriosis and early menopause? Kulkarni et al. (2022) looked this question and found that there just might be. The authors state that early natural menopause (ENM) is the cessation of ovarian function before age 45 years. They report that endometriomas in particular (and some treatments for them) might affect ovarian reserves which could lead to earlier onset of menopause. The authors also note that the increase in inflammatory markers in the peritoneal fluid of those with endometriosis might affect follicular and ovarian function (thus leading to earlier menopause).

The authors report that “in this large, prospective cohort study, we observed that surgically confirmed endometriosis was associated with a significantly greater risk of ENM.” They noted the highest risk for ENM was among those who never used oral contraceptives (OC) or had never given birth (more ovulations throughout the lifetime that used up the number of oocytes at that were present at birth). The authors further comment that “although a meta-analysis found an association between OC use and later age at natural menopause, a recent discovery in the Nurses’ Health Study II population did not support a clear association between duration of OC use (decreasing lifetime number of ovulatory cycles) and risk for ENM.” In the study performed by Kulkarni et al (2022), they did find that “among participants who never used OCs, endometriosis was associated with a 2-fold greater risk for ENM.” The authors comment that “it is likely that OC use masks menopause, which is important to consider in this analysis particularly because women may use OCs to control endometriosis-associated symptoms.”

In the end, the researchers concluded that “endometriosis may be an important risk factor for ENM, and women with endometriosis, particularly those who are nulliparous and never-users of OCs, may be at a higher risk for a shortened reproductive duration.” Early menopause is important because it has an affect on osteoporosis, cardiovascular health, and other aspects of health.

Reference

Kulkarni, M. T., Shafrir, A., Farland, L. V., Terry, K. L., Whitcomb, B. W., Eliassen, A. H., … & Missmer, S. A. (2022). Association Between Laparoscopically Confirmed Endometriosis and Risk of Early Natural Menopause. JAMA Network Open, 5(1), e2144391-e2144391. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/article-abstract/2788287

More updates on diet with endometriosis

A recent systemic review looked at the effect of dietary changes on pain perception in endometriosis. While the researchers went through 2185 studies, only six studies fulfilled their inclusion criteria (reproductive age; laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis; and intervention including any type of dietary change) (Sverrisdóttir, Hansen, & Rudnicki, 2022). Those six studies showed that dietary changes, such as “high intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids, a gluten-free diet and a low nickel diet,” may improve painful endometriosis (Sverrisdóttir, Hansen, & Rudnicki, 2022).

Another study created a short algorithm for dietary suggestions for those with endometriosis. They recommended overall the Mediterranean diet or an antioxidant diet- rich in vitamins, minerals, and polyunsaturated fats (Nirgianakis et al., 2021). For those who have gastrointestinal symptoms, they further recommend a gluten free, low FODMAP, or for a short time low nickel diet (Nirgianakis et al., 2021).

As far as dietary supplements go, a review by Bahat et al. (2022) reports that “magnesium, curcumin, resveratrol, and ECGC were beneficial in animal studies due to their antiangiogenic effects. ” Bahat et al. (2022) also states that “omega 3 and alpha-lipoic acid improved endometriosis-associated pain in human studies” as well as “curcumin, omega 3, NAC, vitamin C, and ECGC supplementation decreased endometriotic lesion size in animal and human studies.” The authors do caution that “low sample size and experimental study design” limits the quality of the evidence and urge that “one should keep in mind that food resources and pharmacological formulas of supplements may have different mechanisms of actions” (Bahat et al., 2022).

For more info on diet and endometriosis, see: https://icarebetter.com/diet-and-nutrition/

References

Bahat, P. Y., Ayhan, I., Ozdemir, E. U., Inceboz, Ü., & Oral, E. (2022). Dietary supplements for treatment of endometriosis: A review. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 93(1). doi: 10.23750/abm.v93i1.11237

Nirgianakis, K., Egger, K., Kalaitzopoulos, D. R., Lanz, S., Bally, L., & Mueller, M. D. (2021). Effectiveness of dietary interventions in the treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review. Reproductive sciences, 1-17. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43032-020-00418-w

Sverrisdóttir, U. Á., Hansen, S., & Rudnicki, M. (2022). Impact of diet on pain perception in women with endometriosis: a systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301211522000781

Endometriosis and rheumatoid arthritis

A couple of recent studies have indicated that those with endometriosis might have a higher risk of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Xue et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021). One study even suggested “in the clinical management of patients with RA, rheumatologists should be especially mindful of the possibility of underlying endometriosis” (Xue et al., 2021). This is echoed by Shigesi et al. (2019) who states that “the observed associations between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases suggest that clinicians need to be aware of the potential coexistence of endometriosis and autoimmune diseases when either is diagnosed.”

Harris et al. (2016) cautions that “it remains to be understood whether and how endometriosis itself, or hysterectomy or other factors associated with endometriosis, is related to risk of…RA.” Alpízar-Rodríguez et al. (2017) found that “laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis was found to be significantly associated with subsequent RA…However, this association was attenuated after adjustment by hysterectomy and oophorectomy, suggesting a possible confounding effect by surgically induced menopause.” This effect of menopause on RA has been noted before- “the peak incidence in females coincides with menopause when the ovarian production of sex hormones drops markedly” (Islander et al., 2011). The effect of female hormones has been noted to influence RA symptoms as well. For instance, one study noted “decreased joint pain during times when estrogen and progesterone levels are high” (Costenbader et al., 2008). Estrogen can have “both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on the immune system” and it has been noted that “the rapid decline in ovarian function and in circulating oestrogens at menopause is associated with spontaneous increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines” (Alpízar-Rodríguez et al., 2017). Part of the effect may be seen in the estrogen receptors, with an increase of ER-β over ER-α receptors in RA synovial tissue (Alpízar-Rodríguez et al., 2017). This increased expression of ER-β receptors is also seen in endometriosis lesions (which can cause increased inflammation) (Bulun et al., 2012).

References

Alpízar-Rodríguez, D., Pluchino, N., Canny, G., Gabay, C., & Finckh, A. (2017). The role of female hormonal factors in the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology, 56(8), 1254-1263. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew318

Bulun, S. E., Monsavais, D., Pavone, M. E., Dyson, M., Xue, Q., Attar, E., … & Su, E. J. (2012, January). Role of estrogen receptor-β in endometriosis. In Seminars in reproductive medicine (Vol. 30, No. 01, pp. 39-45). Thieme Medical Publishers. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4034571/…

Chen, S. F., Yang, Y. C., Hsu, C. Y., & Shen, Y. C. (2021). Risk of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Patients with Endometriosis: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(8), 1160-1164. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8431

Costenbader, K. H., & Manson, J. E. (2008). Do female hormones affect the onset or severity of rheumatoid arthritis?. Arthritis Care & Research, 59(3), 299-301. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/art.23324

Harris, H. R., Costenbader, K. H., Mu, F., Kvaskoff, M., Malspeis, S., Karlson, E. W., & Missmer, S. A. (2016). Endometriosis and the risks of systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 75(7), 1279-1284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207704

Islander, U., Jochems, C., Lagerquist, M. K., Forsblad-d’Elia, H., & Carlsten, H. (2011). Estrogens in rheumatoid arthritis; the immune system and bone. Molecular and cellular endocrinology, 335(1), 14-29. DOI: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.05.018

Xue, Y. H., You, L. T., Ting, H. F., Chen, Y. W., Sheng, Z. Y., Xie, Y. D., … & Wei, J. C. C. (2021). Increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis among patients with endometriosis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Rheumatology, 60(7), 3326-3333. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa784

Shigesi, N., Kvaskoff, M., Kirtley, S., Feng, Q., Fang, H., Knight, J. C., … & Becker, C. M. (2019). The association between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human reproduction update, 25(4), 486-503. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmz014

Endometriosis and Constipation

Endometriosis is associated with several “digestive complaints, including abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, rectal bleeding, and dyschezia” (Raimondo et al., 2022). Raimondo et al. (2022) reports that “chronic constipation (CC) in women with endometriosis varies from 12% to 85%” and results from multiple causes such as inflammation, scar tissue, and damage to pelvic autonomic nerves.

Raimondo et al. (2022) reports that those “with endometriosis are more likely to have pelvic floor muscle dysfunctions” and found by using ultrasounds that hypertonic (too much muscle tone) pelvic floor muscles were found more in those with chronic constipation than those without it. While treating chronic constipation can be challenging, the study states that “specific interventions targeting the pelvic floor hypertonia, such as physiotherapy” might be beneficial.

Another study reports that digestive symptoms such as constipation are due more to the inflammation irritating the digestive tract than to lesions infiltrating the bowel itself (Roman et al., 2012). However, those “presenting with rectal endometriosis were more likely to present cyclic defecation pain (67.9%), cyclic constipation (54.7%) and a significantly longer stool evacuation time, although these complaints were also frequent in the other two groups (38.1 and 33.3% in women with Stage 1 endometriosis and 42.9 and 26.2% in women with deep endometriosis without digestive involvement, respectively)” (Roman et al., 2012). A referral to a gastroenterologist may help improve symptoms, but part of the treatment might include surgery to remove lesions that may be affecting the bowel (Meurs‐Szojda et al., 2011).

For more information on bowel symptoms: https://icarebetter.com/bowel-gi-endometriosis/

References

Meurs‐Szojda, M. M., Mijatovic, V., Felt‐Bersma, R. J. F., & Hompes, P. G. A. (2011). Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation in patients with endometriosis. Colorectal Disease, 13(1), 67-71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02055.x

Raimondo, D., Cocchi, L., Raffone, A., Del Forno, S., Iodice, R., Maletta, M., … & Seracchioli, R. (2022). Pelvic floor dysfunction at transperineal ultrasound and chronic constipation in women with endometriosis. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14088

Roman, H., Ness, J., Suciu, N., Bridoux, V., Gourcerol, G., Leroi, A. M., … & Savoye, G. (2012). Are digestive symptoms in women presenting with pelvic endometriosis specific to lesion localizations? A preliminary prospective study. Human reproduction, 27(12), 3440-3449. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des322

Endometriosis and Heart Disease

There is not much literature about endometriosis and heart disease. Marchandot et al. (2022) reports that there are some overlaps in contributors to both heart disease and endometriosis, such as “chronic inflammation, enhanced oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and cellular proliferation.” Some research indicates “increased arterial stiffness and impaired flow-mediated dilation, a surrogate marker of endothelial dysfunction potentially reversible after surgical treatment, were associated with endometriosis” (Marchandot et al., 2022).

Some risk factors for heart disease have been found in those with endometriosis, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity. Research suggests that the link between hypertension and endometriosis may be because of certain treatments for endometriosis, namely from early hysterectomy/oophorectomy and from use of NSAIDs (Marchandot et al., 2022). In fact, “hysterectomy in women aged 50 years or younger has been associated with a significantly increased risk of ischaemic heart disease, with oophorectomy linked to an increased risk of both [coronary artery disease] and stroke” (Marchandot et al., 2022). Shuster et al. (2010) add that “regardless of the cause…women who experience premature menopause (before age 40 years) or early menopause (between ages 40 and 45 years) experience an increased risk of overall mortality, cardiovascular diseases, neurological diseases, psychiatric diseases, osteoporosis, and other sequelae.” High cholesterol has also been associated with endometriosis- a 25% increased risk in those with endometriosis (Marchandot et al., 2022). Marchandot et al. (2022) also reports that “the role of hormonal treatment strategies for endometriosis, including combined oral contraceptives, progestins, and gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, has been highly questioned regarding a potentially enhanced lipid profile, cardiovascular risk profile, and weight gain.”

Marchandot et al. (2022) urge caution in interpreting results as “only small associations between endometriosis and CVD have been reported in the literature” and that current studies have been limited “by small sample sizes, observational designs, and the specific characteristics of the population from which the samples are derived (high-income countries, cohort study of hospital-based healthcare workers, primarily Caucasian Europeans, etc.).” They also state that endometriosis treatments influence cardiovascular risk factors (“the confounding influence of hormonal, non-hormonal, and pain-related interventions further complicate the cause-and-effect relationship in CV endpoints”) (Marchandot et al. 2022).

References

Marchandot, B., Curtiaud, A., Matsushita, K., Trimaille, A., Host, A., Faller, E., … & Morel, O. (2022). Endometriosis and cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal Open, 2(1), oeac001. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjopen/oeac001

Shuster, L. T., Rhodes, D. J., Gostout, B. S., Grossardt, B. R., & Rocca, W. A. (2010). Premature menopause or early menopause: long-term health consequences. Maturitas, 65(2), 161-166. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.08.003

Fatigue, rest, and pacing

During endometriosis awareness month, the most interacted with post on our Facebook page was about fatigue- which points to how significant it impacts those with endometriosis. Fatigue and pain often go hand in hand- with one aggravating the other. One concept to help prevent flares of pain and fatigue is pacing.

Pacing is about adjusting your activities to your body’s current needs and finding the balance between activity and rest. Pacing doesn’t mean you accomplish less, rather it helps you accomplish your goals while reducing the chance of a pain/fatigue flare. We are familiar with the concept of pacing in running and other forms of exercise:

“Pacing is essentially a strategy that you use to distribute your energy throughout your entire bout of physical activity. Being cognitively aware of how much you are physically exerting yourself will keep you in touch with signs of fatigue and allow better control of performance. Properly controlling your pace during your physical activity can help you prevent working so hard that you’re unable to complete your training in the next session. Pacing allows you to avoid injury…”

(MacPherson, n.d.)

Pacing, according to one study’s participants, can include “breaking down tasks, saying ‘no’, being kind to themselves, using rest breaks, doing something each day, developing a structure and gradually building up activities” (Antcliff et al., 2021). The same study found that some of the main barriers to pacing activities were “wanting to complete tasks, or not wanting to delegate or be perceived as lazy” (Antcliff et al., 2021). Sometimes life’s demands make it difficult- especially with an illness not many people understand. The study had participants include goals such as “socialise with friends, try varying exercises, protect time for hobbies and relaxation, and gradually try activities they had been avoiding due to symptoms” (Antcliff et al., 2021). Sometimes when we feel better, we push ourselves too hard for too long to make up for when we can’t perform our usual activities. Feinberg and Feinberg (n.d.) report that with pacing “you break an activity up into active and rest periods” and that “rest periods are taken before significant increases in pain levels occur.” Pacing may mean that if you have work or an appointment scheduled, then you may need to keep your schedule clear the day before and/or after to be able to recover. It may mean only doing one load of laundry that day. It may mean protecting time for activities that feed your spirit (reading, outdoor time, time with supportive friends or family, etc.).

In the spirit of pacing and taking rest when needed, the admins of our Facebook page will be taking a week off April 2-9, 2022. During this week, our Facebook page will be on pause. This means that it will be read only during that week, so it won’t let you comment, react, post, or request to join. Don’t worry, it’ll go back to usual after that week. After 9 years of continuous volunteer work by the admins and moderators, it’s about time for a break.

See more about fatigue with endometriosis: https://icarebetter.com/fatigue-in-endometriosis/?doing_wp_cron=1594748400.8231060504913330078125

endometriosis signs and symptoms

References

Antcliff, D., Keenan, A. M., Keeley, P., Woby, S., & McGowan, L. (2021). “Pacing does help you get your life back”: The acceptability of a newly developed activity pacing framework for chronic pain/fatigue. Musculoskeletal care. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/msc.1557

Feinberg & Feinberg. (n.d.). Pacing means moving ahead. Retrieved from http://www.cfsselfhelp.org/library/pacing-means-moving-ahead-and-not-falling-behind#:~:text=Pacing%20is%20a%20tool%20that,physical%20activity%20because%20it%20hurts.

MacPherson. (n.d.). How to properly pace yourself during exercise (and why it matters) Retrieved from https://www.vitacost.com/blog/how-to-pace-yourself-to-improve-exercise/

Endometriosis Awareness Week 4

Endometriosis awareness month is still going! As it is our last newsletter for March, we have a bunch of more shareable information, including some myth-busters. Remember, a good link to share is our basic all About Endometriosis that has short and to the point information about endometriosis as well as links for more info. Keep that endo conversation going!

Food is important in our lives! There is no one specific diet for endometriosis. No food, diet, or supplement will “cure” endometriosis, but it can help manage symptoms and is great for overall health and well-being. Your diet needs to be individualized to your specific needs, and it can take quite a bit of experimentation to find what works for you. For more info on diet, see: https://icarebetter.com/diet-and-nutrition/

With the goal to improve symptom management and to feel better overall, some alternative and complementary therapies can be helpful. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/alternative-and-complementary-therapies/

“Hysterectomy is a definitive cure for endometriosis.” Myth-buster: Endometriosis can still persist after a hysterectomy. (A hysterectomy can hep related conditions that involve the uterus however.) https://icarebetter.com/myths-and-misinformation/

“Endo will go away with menopause.” Myth-buster: Endometriosis can still persist after menopause. https://icarebetter.com/myths-and-misinformation/

“Getting pregnant will help.” Myth-buster: Pregnancy is not a cure or treatment for endometriosis. The fact that endometriosis is one of the leading causes of infertility makes this all the more painful. https://icarebetter.com/myths-and-misinformation/

“You’re too young to have endometriosis. ” Myth-buster: Endometriosis can be found in teens and can be found in “advanced” stages. https://icarebetter.com/myths-and-misinformation/

“There wasn’t much endo there so it must not be causing your symptoms.” Or “you only have minimal endometriosis so it’s not affecting your fertility.” Myth-buster: Minimal endometriosis can cause severe symptoms and can affect fertility. https://icarebetter.com/pain-associated-with-minimal-endometriosis/ and https://icarebetter.com/myths-and-misinformation/

“Your symptoms can’t be that bad- it’s just in your head.” Myth-buster: Endometriosis can cause significant symptoms based on very real pathophysiology. https://icarebetter.com/myths-and-misinformation/

Early diagnosis and effective treatment can lead to improved quality of life and lessen the detrimental effects from long term pain and suffering. Increasing awareness of symptoms and best practice treatment is important!

Endometriosis awareness does not end in March for those of us who have suffered from it. If we can each reach out to teach another, then maybe that other person won’t have to go through what we did to not only find a diagnosis but find effective treatment. Please feel free to share the resources provided on our website. (You can further support our work here.)

Endometriosis Awareness Week 3

Endometriosis awareness month is still going! Here is a week’s worth of shareable information. Another good link to share is our basic all About Endometriosis that has short and to the point information about endometriosis as well as links for more info. Keep that endo conversation going!

Infertility is strongly associated with endometriosis. https://icarebetter.com/fertility-issues/ and https://icarebetter.com/infertility-links-2/

Endometriosis is often found with other conditions that can have similar symptoms. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/related-conditions/

Excision is the surgical removal of tissue by cutting out. It differs from ablation/laserization/burning/vaporizing, which are techniques that use a heat source to destroy tissue. Excision allows for a biopsies to be sent to a pathologist for confirmation, and it better ensures that all of the endometriosis lesion is removed. With ablation, it may or may not reach deep enough to destroy all the endometriosis lesion and it does not allow for pathology confirmation. While ablation may work for superficial endometriosis, it leaves the unknown of whether all of the lesion was truly destroyed. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/why-excision-is-recommended/ and https://icarebetter.com/why-see-a-specialist/

Hormonal treatments, while they can relieve symptoms, do not get rid of the disease itself. Symptoms often return rapidly once medications are stopped. Hormonal medication may not stop the progression of disease- this is particularly important where the ureters and/or bowel are involved. Endometriosis lesions are different from normal endometrium (the lining of the uterus), therefore some people’s endometriosis does not respond to progestin therapy. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/hormonal-medications/

Different medications can be used to help alleviate chronic pelvic pain and other related conditions. Alleviate does not necessarily mean eliminate. As long as endometriosis lesions are present, irritation to muscles and nerves that can cause pain will continue. Addressing the underlying problem is important for long term goals. It is also important to address other pain generators, such as pelvic floor dysfunction or interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/pain-medications/ ; https://icarebetter.com/a-quick-guide-to-pain-control/ ; https://icarebetter.com/pain-management/

Endometriosis can cause problems with the surrounding muscles and soft tissues. Pelvic floor spasms, tight muscles, other myofascial changes, and more will often contribute to symptoms (such as pain with defecation or pain with sex). These muscular and soft tissue changes can benefit from pelvic physical therapy. However, appropriate therapy for endometriosis associated problems requires a specific skill set by your physical therapist. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/pelvic-physical-therapy/ and https://icarebetter.com/physical-therapy-resources/

Symptoms from endometriosis, such as pain and fatigue, can impact an individual’s quality of life significantly. This can affect our mental health. Proper treatment for the underlying cause of symptoms can help, but years of symptoms, such as pain or infertility, can create a toll. Seeking care for your mental health is not a sign that your endo is “all in your head”- rather it is another tool to help your overall well-being. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/the-importance-of-mental-health-support-in-endometriosis-2/ ; https://icarebetter.com/mental-health-overview/ ; https://icarebetter.com/choosing-the-right-mental-health-therapist-2/

Endometriosis Awareness Week 2

Endometriosis awareness month has arrived! Here is a week’s worth of shareable information. Another good link to share is our basic all About Endometriosis that has short and to the point information about endometriosis as well as links for more info. Keep that endo conversation going!

For more information, see:

Ultrasounds: https://icarebetter.com/ultrasound-use-with-endometriosis/

MRI’s: https://icarebetter.com/magnetic-resonance-imaging-mris-and-endometriosis/

Negative scans do NOT rule out endometriosis: https://icarebetter.com/but-your-tests-are-all-negative/

While researchers are working to create a reliable test and there are promising ones in development, at this point there are none widely available. Also, response or no response to hormonal medications has NOT been proven to be reliable to diagnose endometriosis. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/labwork-and-blood-tests/ and https://icarebetter.com/but-your-tests-are-all-negative/

When performing surgery, it is important for the surgeon to be familiar with both all the appearances and indications of endometriosis as well as all the locations it might be found. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/the-many-appearances-of-endo/

Endometriosis can be found in many places both in the pelvis and outside of the pelvis. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/locations-of-endometriosis/ and https://icarebetter.com/weird-places-endometriosis-has-been-found/

Endometriosis can cause significant pain even if surgery finds “minimal” lesions. The pain can be from inflammation, nerve irritation, and changes in the myofascia. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/pain-its-complicated/ ; https://icarebetter.com/what-influences-pain-levels/ ; https://icarebetter.com/pain-associated-with-minimal-endometriosis/

Fatigue can significantly impact those with endometriosis. This fatigue can come from inflammation, which can lead to pain which can lead to sleep problems, stress, and depression….which can lead to more fatigue. See more at: https://icarebetter.com/fast-facts-fatigue-with-endometriosis/

Endometriosis patients are often diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). While there can be an overlap in the two conditions, endometriosis can cause symptoms similar to IBS. For more info, see: https://icarebetter.com/bowel-gi-endometriosis/