Endo Basics: What is endometriosis?

Endometriosis has some unique characteristics, and we continue to find out new things about it. Understanding exactly what it is and how it functions can help us make better sense of the symptoms we experience as well as guide our decisions for treatment. Here are some key points to consider:

- Endometriosis is defined as tissue similar to the lining of the uterus (endometrium) that is found outside of the uterus (Becker, 2015). This can be in the pelvis and abdominal area, but has been found in areas outside the pelvis (like the diaphragm). This means it affects more than just reproductive organs! (See Locations of Endometriosis)

- Endometriosis has some key differences from the lining of the uterus in both its structure and function. Endometriotic lesions are capable of high estrogen production and have a resistance to the effects of progesterone (Cristescu, Velişcu, Marinescu, Pătraşcu, Traşcă, & Pop, 2013). Endometriosis can also produce cytokines and prostaglandins and is capable of the growth of new blood vessels and nerves (Hey-Cunningham, Peters, Zevallos, Berbic, Markham, & Fraser, 2013; Reis, Petraglia, & Taylor, 2013; Bulun et al., 2012; Chaban, 2012). (See Role of Estrogen Receptor-β in Endometriosis and Progesterone Resistance in Endometriosis)

- Endometriosis is an inflammatory disorder that can lead to scarring and adhesions (Becker, 2015; Mao & Anastasi, 2010). (See Inflammation with Endometriosis)

- The severity of symptoms does not necessarily correlate with extent of lesions (McCance & Huether, 2014). (See What influences pain levels)

- The location of the lesions and the presence of adhesions can also affect the symptoms experienced (Lu, Zhang, Jiang, Zou, & Li, 2014). (See Locations of Lesions and Where Pain Is Felt)

- Most symptoms arise from chronic inflammation, noxious chemical release such as prostaglandins, effects on the musculoskeletal system, and/or adhesions (Koga, Yoshino, Hirota, Hirata, Harada, & Osuga, 2014). (See Symptoms)

- An estimated 30-50% of patients with endometriosis are infertile due to the inflammatory environment and physical abnormalities such as adhesions (Koga, Yoshino, Hirota, Hirata, Harada, & Osuga, 2014). (See Fertility Issues)

References

Becker, C. (2015). Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Prescriber, 26(20), 17-21.

Bulun, S. E., Monsavais, D., Pavone, M. E., Dyson, M., Xue, Q., Attar, E., … Su, E. J. (2012). Role of Estrogen Receptor-β in Endometriosis. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 30(1), 39–45. http://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1299596

Chaban, V. (2012). Primary afferent nociceptors and visceral pain. INTECH Open Access Publisher. Retrieved from http://www.intechopen.com/books/endometriosis-basicconcepts-and-current-research-trends/primaryafferent-nociceptors-and-visceral-pain

Cristescu, C., Velişcu, A. N. D. R. E. E. A., Marinescu, B., Pătraşcu, A. N. C. A., Traşcă, E. T., & Pop, O. T. (2013). Endometriosis–clinical approach based on histological findings. Rom J Morphol Embryol, 54(1), 91-97.

Hey-Cunningham, A. J., Peters, K. M., Zevallos, H. B., Berbic, M., Markham, R., & Fraser, I. S. (2013). Angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis and neurogenesis in endometriosis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed), 5, 1033-56.

Koga, K., Yoshino, O., Hirota, Y., Hirata, T., Harada, M., & Osuga, Y. (2014). Infertility Treatment of Endometriosis Patients. In Endometriosis (pp. 431-443). Springer Japan.

Lu, Z., Zhang, W., Jiang, S., Zou, J., & Li, Y. (2014). Effect of lesion location on endometriotic adhesion and angiogenesis in SCID mice. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics, 289(4), 823-830.

Mao, A. J., & Anastasi, J. K. (2010). Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: The role of the advanced practice nurse in primary care. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 22(2), 109-116.

McCance, K. L., & Huether, S. E. (2014). Pathophysiology: The Biological Basis for Disease in Adults and Children (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Reis, F. M., Petraglia, F., & Taylor, R. N. (2013). Endometriosis: hormone regulation and clinical consequences of chemotaxis and apoptosis. Human reproduction update, 19(4), 406-418.

Self-Care During the Holidays

Holidays can be fun and festive but can also be a source of stress for those dealing with a chronic illness. It can be hard for friends and family to understand the pain and fatigue that makes it difficult for us to participate in or plan for various activities. Symptoms, like heavy bleeding, significant pain, fatigue, or bowel symptoms, can make even everyday activities difficult. There is also the added strain on finances from medical care and lost wages.

Remember that others may not understand and that’s okay. There will be those who will be sympathetic even if they don’t comprehend…and there will be those who won’t. Focus your energy on what means the most to you.

Sometimes the pressure comes ourselves and not from others. Don’t be so hard on yourself. Chronic illness can take a toll physically, mentally, and emotionally. It’s important to take care of each of these aspects of health during the holidays. Rest for body and mind is important. It’s okay to take a break. It’s okay to turn your phone off. It’s okay to not check your messages or social media. It’s okay to disconnect when you need to. It’s okay to say “no” and not offer deeper explanation of why.

What are your tips for dealing with the holidays? Head over to our Facebook group and drop a note in the post.

Links:

- Chronic Illness During the Holidays

- How to Enjoy the Holiday Season When You’re Chronically Ill

- How to survive the holidays when you’re chronically ill

Looking at surgery

Let’s face it. Surgery is scary. Whether it’s your first or your fifth. I think for those of us who have suffered for a long time, the unknown of “will they find anything, will it help, will it be worth it?” lingers in our minds. While surgery is not a magical fix-all, we want to feel as confident as possible when deciding on surgery.

First, it’s important to understand your disease and other related conditions that may be playing part of your symptoms. Start here to begin that learning.

Second point is to know your options for treatment and discuss the pros and cons with your provider.

Third is making an informed choice based on that knowledge. A little research can go a long way. When discussing surgery, here are some things to consider. We have many members on our Facebook group who have recommended surgeons to others based on their individual results. We can do our due diligence when asking others about a surgeon or asking questions ourselves. But what if this was taken a step further?

What is surgical vetting?

Surgical vetting involves peer reviewed assessment and feedback on video documented surgical procedures. For instance, a 2013 study looked at the different skill sets that played into surgical outcomes (Birkmeyer et al., 2013). The authors stated that:

“Clinical outcomes after many complex surgical procedures vary widely across hospitals and surgeons. Although it has been assumed that the proficiency of the operating surgeon is an important factor underlying such variation, empirical data are lacking on the relationships between technical skill and postoperative outcomes.” (Birkmeyer et al., 2013)

In order to assess this, the study utilized this method:

“Each surgeon submitted a single representative videotape of himself or herself performing a laparoscopic gastric bypass. Each videotape was rated in various domains of technical skill on a scale of 1 to 5 (with higher scores indicating more advanced skill) by at least 10 peer surgeons who were unaware of the identity of the operating surgeon. We then assessed relationships between these skill ratings and risk-adjusted complication rates, using data from a prospective, externally audited, clinical-outcomes registry involving 10,343 patients.” (Birkmeyer et al., 2013)

Their findings?

“The technical skill of practicing bariatric surgeons varied widely, and greater skill was associated with fewer postoperative complications and lower rates of reoperation, readmission, and visits to the emergency department. Although these findings are preliminary, they suggest that peer rating of operative skill may be an effective strategy for assessing a surgeon’s proficiency.” (Birkmeyer et al., 2013)

In 2016, a follow up article on that study noted:

“Recently, enthusiasm has been growing to tackle the challenges of directly evaluating and improving surgeon performance using intraoperative video. This work with practicing surgeons builds on the previous experience of using video to assess laparoscopic skills among residents…. While the use of video analysis to improve skill and technique is promising, one particularly important challenge must be recognized: building surgeon trust and social capital. In the bariatric surgery examples described above, this was accomplished over time through a spirit of collaboration that fostered relationships and a shared goal of quality improvement among surgeons in Michigan. For this process to succeed, these initiatives would first need to be piloted on a smaller scale through individual institutions or regional collaboratives to build social capital and ensure surgeon “buy-in”. Once established locally, a professional society (e.g. the American College of Surgeons, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, depending on the specialty or interest) could serve as a potential framework through which a program could be implemented more broadly. It will be necessary to clearly establish that skill assessment would be strictly for quality improvement purposes, ensuring complete confidentiality for participating surgeons. Through these steps, a collaborative infrastructure can be built to implement video-based analysis in a real-world practice setting.” (Grenda, Pradarelli, & Dimick, 2016)

Other studies have utilized similar methods. For instance, one done in 2010 to assess the skill accreditation system for laparoscopic gastroenterologic surgeons in Japan used “non-edited videotapes” that “were assessed by two judges in a double-blinded fashion with strict criteria” (Mori, Kimura, & Kitajima, 2010). Their study found that “surgeons assessed by this system as qualified experienced less frequent complications when compared to those who failed” (Mori, Kimura, & Kitajima, 2010). A similar approach was taken for urological laparoscopy with an 8 year follow up of the system (Matsuda et al., 2006; Matsuda et al., 2014). One article notes that “surgeons are under enormous pressure to continually improve and learn new surgical skills” and that the use of video technology can be useful to that means, especially as it is “becoming easier as most of our surgical platforms (e.g., laparoscopic, and endoscopy) now have video recording technology built in and video editing software has become more user friendly” (Ibrahim, Varban, & Dimick, 2016). The use of this technology may at one point lead to “future applications of video technology are being developed, including possible integration into accreditation and board certification” (Ibrahim, Varban, & Dimick, 2016).

How can this be used to help patients with endometriosis?

There are many dedicated, hard-working, and skilled surgeons out there, but it can be difficult for patients and other providers to connect with them. Not only can video vetting assist in surgeons being recognized for their skill, but it can also serve as a way for other providers and patients to find them! It can help connect patients and providers with surgeons with specific skill sets that a case may need. For instance, if a surgeon has demonstrated proficiency in working on thoracic endometriosis, then a directory could help providers and patients connect with not only that surgeon, but a multidisciplinary team to address that specialized care need. While there are no guarantees in life, surgical vetting can be another tool in our toolbelt to try to make the best decision we can.

References

Birkmeyer, J. D., Finks, J. F., O’Reilly, A., Oerline, M., Carlin, A. M., Nunn, A. R., … & Birkmeyer, N. J. (2013). Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(15), 1434-1442. Retrieved from https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsa1300625

Grenda, T. R., Pradarelli, J. C., & Dimick, J. B. (2016). Using surgical video to improve technique and skill. Annals of surgery, 264(1), 32. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5671768/

Ibrahim, A. M., Varban, O. A., & Dimick, J. B. (2016). Novel uses of video to accelerate the surgical learning curve. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques, 26(4), 240-242. Retrieved from https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/lap.2016.0100

Matsuda, T., Ono, Y., Terachi, T., Naito, S., Baba, S., Miki, T., … & Okuyama, A. (2006). The endoscopic surgical skill qualification system in urological laparoscopy: a novel system in Japan. The Journal of urology, 176(5), 2168-2172. Retrieved from https://www.auajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.034

Matsuda, T., Kanayama, H., Ono, Y., Kawauchi, A., Mizoguchi, H., Nakagawa, K., … & Referee Committee of the Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System in Urological Laparoscopy. (2014). Reliability of laparoscopic skills assessment on video: 8-year results of the endoscopic surgical skill qualification system in Japan. Journal of endourology, 28(11), 1374-1378. Retrieved from https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/end.2014.0092

Mori, T., Kimura, T., & Kitajima, M. (2010). Skill accreditation system for laparoscopic gastroenterologic surgeons in Japan. Minimally Invasive Therapy & Allied Technologies, 19(1), 18-23. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/13645700903492969

Sciatic Pain and Endometriosis

While endometriosis may not necessarily have to be on the sciatic nerve to cause similar symptoms, there have been some cases documented of that happening. Some symptoms could be: cyclical pain along the sciatic nerve (sciatica), back pain, gluteal pain radiating to the front of the thigh and outside the lower leg, positive straight leg raise test (seen in low back disc injuries as well), sensory loss, changes in reflexes, and muscle weakness (Foti et al., 2018). There are multiple case studies demonstrating endometriosis affecting the sciatic nerve region. However, symptoms can occur from lesions near those areas (like the side posterior pelvic region) (Vilos, Vilos, & Haebe, 2002). Pelvic floor dysfunction and other myofascial disorders (such as piriformis syndrome) can also cause similar symptoms (Cass, 2015; Weiss, Rich, & Swisher, 2012). As is often seen with endometriosis, there may be more than one pain/symptom generator present. This might mean utilizing different providers, such as a pelvic physical therapist as well as a surgeon, in order to address all the underlying issues. (See Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Physical Therapy Resources )

Links:

- Can endometriosis affect the sciatic region?

- Deep endometriosis of sacral root, piriform muscle, low rectum: sciatic pain, dysuria and occlusion – a horrific disease

- Is Sciatic Endometriosis Possible?

- Video: Endometriosis of the Sciatic Nerve with large infiltration of the pelvic sidewall

Studies:

- Vilos, G. A., Vilos, A. W., & Haebe, J. J. (2002). Laparoscopic findings, management, histopathology, and outcomes in 25 women with cyclic leg pain. The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, 9(2), 145-151. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1074380405601223

“Cyclic leg signs and symptoms were associated with pelvic peritoneal pockets, endometriosis nodules, or surface endometriosis of the posterolateral pelvic peritoneum. We hypothesize that the pain associated with these lesions is more likely referred pain originating from pelvic peritoneum than direct irritation of the lumbosacral plexus of the sciatic nerve.”

- Troyer, M. R. (2007). Differential diagnosis of endometriosis in a young adult woman with nonspecific low back pain. Physical therapy, 87(6), 801-810. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/87/6/801/2747261

“Endometriosis is a common gynecological disorder that can cause musculoskeletal symptoms and manifest as nonspecific low back pain. The patient was a 25-year-old woman who reported the sudden onset of severe left-sided lumbosacral, lower quadrant, buttock, and thigh pain. The physical therapist examination revealed findings suggestive of a pelvic visceral disorder during the diagnostic process. The physical therapist referred the patient for medical consultation, and she was later diagnosed by a gynecologist with endometriosis and a left ovarian cyst.”

- Bove, G. M. (2016). A model for radiating leg pain of endometriosis. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies, 20(4), 931-936. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5116304/

“Radiating leg pain related to the menstrual cycle has been reported as a complication of endometriosis in a number of case studies (Baker et al., 1966; Bjornsson, 1976; Denton & Sherrill, 1955; Floyd et al., 2011; Forrest & Brooks, 1972; Head et al., 1962; Motamedi et al., 2015; Pacchiarotti et al., 2013), and in two surveys (Missmer & Bove, 2011; Walch et al., 2014). A consistent and thus perhaps key diagnostic feature seems to be the cyclical or catamenial nature of the symptom, especially earlier in the progression of the endometriosis (Capek et al., 2016; Dhote et al., 1996; Moeser et al., 1990; Takata & Takahashi, 1994; Zager et al., 1998). However, the symptom duration usually expands with endometriosis progression, developing into constant pain if left untreated.

“Examination findings in women with leg pain due to endometriosis are typical of sciatica due to other causes (Torkelson et al., 1988), including painful straight leg raising testing, and may also include a diminished Achilles tendon reflex, mild muscular atrophy, and tenderness of the sciatic nerve at the sciatic notch. Lumbar spinal investigations (myelogram, CSF analysis) are usually unremarkable, but magnetic resonance imaging can demonstrate larger lesions (Binkovitz et al., 1991; Cottier et al., 1995; Yekeler et al., 2004).

“Surgical descriptions of sciatic endometriosis describe inflammatory lesions that involve surrounding structures that are not necessarily otherwise diseased (Descamps et al., 1995; Yekeler et al., 2004). In an animal model, it has been shown that a focal inflammation of the sciatic nerve (called sciatic neuritis) evokes mechanical sensitivity in the axons of a subset of nociceptive (potentially pain-evoking) neurons without causing overt nerve damage (Bove et al., 2003; Dilley & Bove, 2008; Dilley et al., 2005). Furthermore, the sheaths of nerve trunks are innervated by mechanically and chemically-sensitive nociceptors (Bove & Light, 1995a, b, 1997), which also participate in maintaining the local environment of the nerve (Sauer et al., 1999). These findings suggest that inflamed nerves are a source of pain perceived as coming from the nerve and as coming from the structure(s) that the nerve innervates.”

- Lomoro, P., Simonetti, I., Nanni, A., Cassone, R., Di Pietto, F., Vinci, G., … & Sammarchi, L. (2019). Extrapelvic Sciatic Nerve Endometriosis, the Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Case Report and Systematic Review. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography, 43(6), 976-980. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/jcat/Abstract/2019/11000/Extrapelvic_Sciatic_Nerve_Endometriosis,_the_Role.25.aspx

“Endometriosis (EN) is a common gynecological condition characterized by the presence of functional endometrium located outside the uterine cavity. Sciatic nerve (SN) is rarely affected by EN. Magnetic resonance imaging allows a direct visualization of the spinal and SN, and it is the modality of choice for the study of SN involvement in extrapelvic EN. We report a case of an endometrioma located in the right SN with a systematic review of the literature.”

- Le, A., Ocampo, J. E., & Zaritsky, E. (2020). Nerve Evaluation during Laparoscopic Endometriosis Resection. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, 27(7), S106. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1553465020305446

“The patient is a 49-year-old perimenopausal woman with dysmenorrhea and a left ovarian cyst who presented for evaluation of new onset left hip and leg pain. The left ovarian cyst was first noted 4 years ago and the patient declined surgery at that time, instead opting for surveillance with repeat imaging which now demonstrated an interval increase in the cyst size. The patient had an extensive evaluation for her leg pain including MRI and nerve conduction studies which were all unremarkable. The patient declined medical management or definitive surgical treatment of the suspected endometriosis. She opted for a diagnostic laparoscopy and left ovarian cystectomy.”

- Roca, M. U., Bandeo, L., Saucedo, M. A., Bala, M., Binaghi, D., Chertcoff, A., … & Pardal, M. F. (2019). Cyclic Sciatica: Presentation of a Case With Intra and Extrapelvic Endometriosis Affecting the Sciatic Nerve and Utility of MR Neurography (P3. 4-026). Retrieved from https://n.neurology.org/content/92/15_Supplement/P3.4-026.abstract

“A 35-year-old female patient consulted for right low back pain extending along her posterior thigh, calf and foot since 2 years. The pain was recurrent, acute in onset, lasted several days and gradually diminished until disappearing. It was refractory to common analgesics and during the crisis she had difficulties to walk. Neurologist requested a calendar of pain in which the relationship between the menstrual cycle and the pain became evidenced. We performed MRN of the lumbo sacral plexus that showed multiple endometriotic implants in ovaries, L5-S1 roots and a huge one on the sciatic nerve (intra and extrapelvic segment). The patient started oral contraceptives but presented progressive worsening of pain until it became constant and developed step page. Electromyogram showed acute and chronic axonal damage in the sciatic nerve distribution. Medical treatment was changed to leuprolide acetate. The patient evolved with improvement of ovarian endometriosis but persistence of sciatic nerve lesions, leg pain and weakness up to now. Surgical option was considered.”

- Mannan, K., Altaf, F., Maniar, S., Tirabosco, R., Sinisi, M., & Carlstedt, T. (2008). Cyclical sciatica: endometriosis of the sciatic nerve. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume, 90(1), 98-101. Retrieved from https://online.boneandjoint.org.uk/doi/full/10.1302/0301-620X.90B1.19832

“A 25-year-old woman presented to her general practitioner with a two-month history of constant pain in her thigh. There was no history of trauma and the onset was insidious. A diagnosis of a soft-tissue injury was made. However, despite anti-inflammatory medication and physiotherapy she developed increasing pain, typically sciatic in nature, from the left buttock, radiating down the posterolateral aspect of the leg and heel. This would escalate to a severe left-sided sciatic pain during menstruation. Two years later she had developed a limp and was referred to an orthopaedic surgeon. At the time of clinical assessment she had marked pain (Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)2 7 and Peripheral Nerve Injury (PNI) scale3 2) and required either two crutches or a wheelchair. On examination, she had an antalgic gait and was unable to bear weight fully on her left leg because of the pain in her buttock and leg. The pain was exacerbated by hip flexion and knee extension. There was no apparent muscle wasting or sympathetic changes in the leg and foot. Palpation of the left gluteal region, especially over the sciatic notch, was painful. Motor power was preserved throughout the leg, except for some weakness in the biceps femoris. Straight-leg raising was to 30° only. Reflexes were present, but the ankle jerk only with reinforcement. Sensation to pin-prick, temperature and light touch was reduced in the heel and sole of the foot.

“The diagnosis of sciatic endometriosis was considered…Histopathological examination confirmed endometriosis of the sciatic nerve with no evidence of malignancy (Figs 4 and 5). Post-operatively and at 12 months follow-up her pain was considerably relieved (VAS2 2, PNI3 1). She was able to walk without crutches and could straighten the leg. There was an improvement in sensation over the heel and sole of the foot to pin-prick, temperature and light touch. She was referred to a gynaecologist, who performed a laparoscopy which now showed no evidence of intra-pelvic endometriosis.”

- Yanchun, L., Yunhe, Z., Meng, X., Shuqin, C., Qingtang, Z., & Shuzhong, Y. (2019). Removal of an endometrioma passing through the left greater sciatic foramen using a concomitant laparoscopic and transgluteal approach: case report. BMC women’s health, 19(1), 95. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6624926/

“A 20-year-old woman presented with complaints of severe dysmenorrhea lasting for more than 6 years and dysfunction of her left lower limb lasting for approximately 4 months. Both CT and MRI demonstrated a suspected intrapelvic and extrapelvic endometriotic cyst (7.3 cm × 8.1 cm × 6.5 cm) passing through the left greater sciatic foramen. Laparoscopic exploration showed a cyst full of dark fluid occupying the left obturator fossa and extending outside the pelvis. A novel combination of transgluteal laparoscopy was performed for complete resection of the cyst and decompression of the sciatic nerve. Postoperative pathology confirmed the diagnosis of endometriosis. Long-term follow-up observation showed persistent pain relief and lower limb function recovery in the patient.”

- Osório, F., Alves, J., Pereira, J., Magro, M., Barata, S., Guerra, A., & Setúbal, A. (2018). Obturator internus muscle endometriosis with nerve involvement: a rare clinical presentation. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology, 25(2), 330-333. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1553465017304004

“We report a case of a 32-year-old patient who presented with cyclic leg pain in the inner right thigh radiating to the knee caused by a cystic endometriotic mass in the obturator internus muscle with nerve retraction…. Surgical removal of the mass was performed using the laparoscopic approach… A mass located within the right obturator internus muscle, below the right iliac external vein, behind the corona mortis vein, and lateral to the right obturator nerve was identified. The whole region was inflamed, and the nerve was partially involved. Dissection was performed carefully with rupture of the tumor, releasing a chocolate like fluid (Fig. 2), and the cyst was removed. Pathology examination was consistent with endometriosis. Patient improvement was observed, with pain relief and improved ability for right limb mobilization.”

- Lemos, N., D’Amico, N., Marques, R., Kamergorodsky, G., Schor, E., & Girão, M. J. (2016). Recognition and treatment of endometriosis involving the sacral nerve roots. International urogynecology journal, 27(1), 147-150. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00192-015-2703-z

“The signs suggestive of intrapelvic nerve involvement include perineal pain or pain irradiating to the lower limbs, lower urinary tract symptoms, tenesmus or dyschezia associated with gluteal pain. Whenever deeply infiltrating lesions are present, the patient must be asked about those symptoms and specific MRI sequences for the sacral plexus must be taken, so that the equipment and team can be arranged and proper treatment performed.”

- Walch, K., Kernstock, T., Poschalko-Hammerle, G., Gleiß, A., Staudigl, C., & Wenzl, R. (2014). Prevalence and severity of cyclic leg pain in women with endometriosis and in controls–effect of laparoscopic surgery. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 179, 51-57. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301211514003029

“Before surgery, more women were affected by leg pain in the endometriosis group, compared to the control group (45.5% and 25.9%, respectively). Preoperative VAS scores for leg pain, however, were not significantly different between the two groups. A moderate correlation in the preoperative VAS scores between leg pain and dysmenorrhea was observed. After laparoscopy, we found a significant improvement in leg pain intensity in both groups. Conclusions: The prevalence of leg pain is increased in endometriosis, while leg pain intensity is not, compared to women without endometriosis. Laparoscopic surgery—even without preparation and decompression of nerve tissue—is associated with an improvement in pain intensity in women with endometriosis, as well as in the group without endometriosis.”

- Weiss, P. M., Rich, J., & Swisher, E. (2012). Pelvic floor spasm: the missing link in chronic pelvic pain. Contemporary OB/GYN. Retrieved from https://www.contemporaryobgyn.net/view/pelvic-floor-spasm-missing-link-chronic-pelvic-pain

“Pelvic floor dysfunction can also arise in response to other common chronic pain syndromes, such as endometriosis, irritable bowel disease, vulvodynia, and interstitial cystitis. A prospective evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain of various etiologies found abnormal musculoskeletal findings in 37%, versus 5% of controls.7 For this reason, the pelvic floor should be included in any evaluation regardless of the suspected source of pelvic pain.”

References

Foti, P. V., Farina, R., Palmucci, S., Vizzini, I. A. A., Libertini, N., Coronella, M., … & Milone, P. (2018). Endometriosis: clinical features, MR imaging findings and pathologic correlation. Insights into imaging, 9(2), 149-172. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13244-017-0591-0

Vilos, G. A., Vilos, A. W., & Haebe, J. J. (2002). Laparoscopic findings, management, histopathology, and outcomes in 25 women with cyclic leg pain. The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, 9(2), 145-151. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1074380405601223

Symptoms- from typical to atypical

Endometriosis symptoms can vary widely in both presentation and severity. While endometriosis can present with “typical” symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain during menstruation, it can also present with symptoms not readily attributed to endometriosis. One example is sciatica type symptoms- pain running along the lines of the sciatic nerve (from the low back down the back of the leg). For some, infertility rather than pain is the first sign that they note.

Pelvic Endometriosis:

The following study performed a literature review on pelvic endometriosis in order to identify signs and symptoms (hoping to lead to more timely investigation into the possibility of endometriosis).

Riazi, H., Tehranian, N., Ziaei, S., Mohammadi, E., Hajizadeh, E., & Montazeri, A. (2015). Clinical diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: a scoping review. BMC women’s health, 15(1), 39. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4450847/pdf/12905_2015_Article_196.pdf

- Pain:

- Pain with periods (dysmenorrhea)- during and at the end of menstruation

- Pelvic pain before and during menstruation

- Pain during sexual intercourse or after sex (dyspareunia)

- Lower abdominal pain or suprapubic pain

- Lower back pain and loin pain

- Chronic pelvic pain (lasting ≥6 months)

- Pain between periods (intermenstrual pain)

- Ovulation pain

- Rectal pain (throbbing, dull or sharp, exacerbated by physical activity)

- Pain often worsened over time and changed in character

- Menstrual symptoms:

- Heavy or prolonged periods (hypermenorrhea or menorrhagia)

- Premenstrual spotting for 2–4 days

- Mid cycle bleeding

- Irregular bleeding

- Irregular periods

- Urinary problems:

- Pain with urination (dysuria)

- Blood in urine (hematuria)

- Urinary frequency

- Urinary tract infection

- Inflammation of the bladder (cystitis)

- Digestive symptoms:

- Abdominal bloating

- Diarrhea with period

- Painful bowel movements

- Painful defecation (dyschezia) during periods

- Blood in stool (hematochezia)

- Nausea and stomach upset around periods

- Constipation

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Early satiety

- Gynecologic comorbidities:

- Gynecological infections and low resistance to infection

- Candidiasis

- Infertility

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Ovarian cysts

- Bleeding after sex (postcoital bleeding)

- Comorbidities:

- wide range of allergies and allergic disease

- dizziness

- migraines and headaches at the time of period or before

- mitral valve prolapse

- Social life symptoms:

- Inability to carry on normal activities including work or school

- Depressed and anxious feelings

- Irritability or premenstrual tension syndrome

- Psychoemotional distress

- Musculoskeletal symptoms:

- muscle/bone pain

- joint pain

- leg pain

- Other symptoms:

- Chronic fatigue, exhaustion, low energy

- Low-grade fever

- Burning or hypersensitivity- suggestive of a neuropathic component

- Mictalgia (pain with urination)

Some signs of endometriosis in other places/specific places might include:

- Bowel:

- Abdominal pain

- Disordered defecation (dyschezia)

- Having to strain harder to have a bowel movement or having cramp like pain in the rectum (tenesmus)

- Bloating, abdominal discomfort (meteorism)

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Alternating constipation/diarrhea

- Painful defecation

- Dark feces containing blood (melena) or fresh blood with bowel movements (hematochezia) (Charatsi et al., 2018)

- “The gastrointestinal tract is the most common location of extrapelvic endometriosis (and extragenital pelvic endometriosis when referring to rectum, sigmoid, and bladder)… Symptoms, in general, include crampy abdominal pain, dyschezia, tenesmus, meteorism, constipation, melena, diarrhea, vomiting, hematochezia, pain on defecation, and after meals. The traditional cyclical pattern of symptomatology has not been confirmed by recent studies which postulate a rather noncyclical chronic pelvic pain as a more persistent symptom [32]. Cyclical symptoms that aggravate during menses, however, have also been reported in a small number of patients [33, 34]. Since intestinal mucosa is rarely affected, rectal bleeding is also an unusual symptom, reported in 0 to 15% to 30% of patients [15, 35, 36]. Bleeding can also occur due to severe bowel obstruction and ischemia [32, 37]. Acute bowel obstruction due to stenosis is a scarce complication reported only in cases when severe small bowel involvement is present or in the presence of dense pelvic adhesions.” (Charatsi et al., 2018)

- Bladder and Ureters:

- “feeling the need to urinate urgently,

- frequent urination,

- pain when the bladder is full,

- burning or painful sensations when passing urine,

- blood in the urine,

- pelvic pain,

- lower back pain (on one side)” (Medical News Today, 2018)

- None (if endometriosis is close to the ureters there may be no presenting symptoms)

- “Vesical endometriosis is usually presented with suprapubic and back pain or with irritative voiding symptoms [96]. These symptoms generally occur on a cyclic basis and are exaggerated during menstruation. Less than 20% of patients however report cyclical menstrual hematuria, which is considered a pathognomic sign for bladder endometriosis [97–99]. Bladder detrusor endometriosis symptoms may cause symptoms similar to painful bladder syndrome; therefore, diagnosis of bladder endometriosis should be considered in patients with recurrent dysuria and suprapubic pain [100]. Clinical symptoms of ureteral endometriosis are often silent [76, 101, 102]. Since the extrinsic form of the disease is more common resulting from endometriosis affecting the rectovaginal septum or uterosacral ligaments and surrounding tissues, patients present with dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and pelvic pain [103]. Abdominal pain is the predominant symptom, occurring in 45% of symptomatic patients [93, 104–106]. Symptoms are often cyclical when the ureter is involved, and cyclic microscopic hematuria is a hallmark of intrinsic ureteral disease [95, 107, 108]. There is a limited correlation between severity of symptoms and the degree of obstruction of the ureter. High degree of obstruction may proceed for a long time without symptoms, leading to deterioration of renal function [76]. Unfortunately, ureteral endometriosis is often asymptomatic leading to silent obstructive uropathy and renal failure [109].” (Charatsi et al., 2018)

- Thoracic (Diaphragm and Lung):

- “…many patients being asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients often experience a constellation of temporal symptoms and radiologic findings with menstruation, including catamenial pneumothorax (80%), catamenial hemothorax (14%), catamenial hemoptysis (5%), and, rarely, pulmonary nodules.However, symptoms have been reported before menstruation, during the periovulatory period, and following intercourse.Symptoms of thoracic endometriosis are largely related to the anatomic location of the lesions. Pleural TES typically presents with symptoms of catamenial pneumothorax and chest or shoulder pain. Catamenial pneumothorax is defined as recurrent pneumothorax occurring within 72 h of the onset of menstruation. The symptoms experienced by patients are comparable to those of spontaneous pneumothorax and include pleuritic chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath. Furthermore, diaphragmatic irritation may produce referred pain to the periscapular region or radiation to the neck (most often right-sided). The right hemithorax is involved in up to 92% of cases, with 5% of cases involving the left hemithorax and 3% experiencing bilateral involvement. Catamenial hemothorax is a less common manifestation of pleural TES. Similar to catamenial pneumothorax, it presents with nonspecific symptoms of cough, shortness of breath, and pleuritic chest pain. It is predominantly right-sided, although rare cases of left-sided hemothorax have been reported.Less common bronchopulmonary TES presents as mild to moderate catamenial hemoptysis or as rare lung nodules identified on imaging. Massive, life-threatening hemoptysis is rare. Pulmonary nodules can be an incidental finding at the time of imaging or can occur in symptomatic patients. They can vary in size from 0.5 to 3 cm. Outside of the well-established clinical manifestations of TES, cases of isolated diaphragmatic endometriosis are typically asymptomatic but can result in irritation of the phrenic nerve. This can produce a syndrome of only catamenial pain, presenting as cyclic neck, shoulder, right upper quadrant, or epigastric pain.” (Nezhat et al., 2019)

(catamenial refers to menstruation; pneumothorax is air leaking into the space between the lung lining; hemothorax is blood leaking into the space between the lung lining; hemoptysis is coughing up blood)

- Sciatic: pain in the buttock or hip area; pain, numbness, and/or weakness going down the leg; symptoms may initially occur with ovulation or menses (Sarr et al., 2018)

- Scar: “Symptoms at presentation included the presence of a palpable mass at the level of the scar (78.57%), non-cyclic and cyclic abdominal pain (50%, 42.85% respectively), bleeding form mass (7.14%) and swelling of the affected area (7.14%).” (Malutan et al., 2017)

This qualitative study describes symptoms as experienced by individuals with endometriosis:

- Moradi, M., Parker, M., Sneddon, A., Lopez, V., & Ellwood, D. (2014). Impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a qualitative study. BMC women’s health, 14(1), 123. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1472-6874-14-123

“All women had suffered severe and progressive pain during menstrual and non-menstrual phases in different areas such as the lower abdomen, bowel, bladder, lower back and legs that significantly affected their lives. Other symptoms were fatigue, tiredness, bloating, bladder urgency, bowel symptoms (diarrhoea), bladder symptoms and sleep disturbances due to pain….

“The women described the pain as ‘sharp’, ‘stabbing’, ‘horrendous’, ‘tearing’, ‘debilitating’ and ‘breath-catching’. Severe pain was accompanied by vomiting and nausea and was made worse by moving or going to the toilet. The frequency of pain differed between the women with some reporting pain every day, some lasting for three weeks out of each menstrual cycle, and another for one year…

“Most of the women complained of dyspareunia during and/or after sex….

“Heavy and/or irregular bleeding was another symptom experienced but in some women, it was a side effect of endometriosis treatment. Bleeding when exercising and after sex were experienced by only a few women. Women and their partners were particularly worried when bleeding occurred after sex….

“Most women reported that endometriosis had significant impacts as they lived through it every day of their lives…. The physical impact was associated with symptoms, treatment side-effects and changes in physical appearance. Pain in particular was reported to limit their normal daily physical activity like, walking and exercise. Women who had small children mentioned that they were not able to care for them as they would like…Fatigue and limited energy were also among reported physical impacts of endometriosis. Although infertility was primarily a physical impact of endometriosis, it had a negative impact on the psychological health, relationship, and financial status of the women….

“Most women reported a reduction in social activity, and opted to stay home, and missed events because of severe symptoms especially pain, bleeding and fatigue. They resorted to using up their annual leave after exhausting their sick leave because of their disease. Some women also decreased their sport or leisure activities and some gave up their routine sport including water ski, horse-riding, swimming and snow skiing….”

References

Charatsi, D., Koukoura, O., Ntavela, I. G., Chintziou, F., Gkorila, G., Tsagkoulis, M., … & Daponte, A. (2018). Gastrointestinal and urinary tract endometriosis: a review on the commonest locations of extrapelvic endometriosis. Advances in medicine, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/amed/2018/3461209/

Malutan, A. M., Simon, I., Ciortea, R., Mocan-Hognogi, R. F., Dudea, M., & Mihu, D. (2017). Surgical scar endometriosis: a series of 14 patients and brief review of literature. Clujul Medical, 90(4), 411. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5683831/

Medical News Today. (2018). Can endometriosis cause bladder pain?. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321439

Nezhat, C., Lindheim, S. R., Backhus, L., Vu, M., Vang, N., Nezhat, A., & Nezhat, C. (2019). Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: a review of diagnosis and management. JSLS: Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons, 23(3). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6684338/

Saar, T. D., Pacquée, S., Conrad, D. H., Sarofim, M., De Rosnay, P., Rosen, D., … & Chou, D. (2018). Endometriosis involving the sciatic nerve: a case report of isolated endometriosis of the sciatic nerve and review of the literature. Gynecology and minimally invasive therapy, 7(2), 81. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6113996/

Red Flags: Myths and Misinformation

There are several red flags of perpetual myths/misinformation to watch for when evaluating information about endometriosis. Here are a few to be aware of:

- “Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment for endometriosis.” Or variations of this theme: “Removing your uterus and/or ovaries will cure you”. Many people with endometriosis also experience problems with their uterus or ovaries (such as adenomyosis, fibroids, and other conditions that can contribute to chronic pelvic pain) that could benefit from a hysterectomy. However, using a hysterectomy to treat endometriosis alone may still leave you susceptible to continued symptoms and other problems from remaining lesions [one example: hydronephrosis from endometriosis left around ureters (Bawin, Troisfontaines, & Nisolle, 2013)].

- “Persistent or recurrent endometriosis after a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH BSO) has been reported by several investigators.” (Hasty & Murphy, 1995)

- “According to literature, there are no randomized controlled trials for hysterectomy as the treatment for endometriosis.” (Bellelis, 2019)

- “Endometriosis which is not removed at the time of hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy may represent after a variable time interval with many or all of the symptoms which prompted the original surgery. This tissue can be highly active and responsive to exogenous hormonal stimulation. In the presence of troublesome symptoms, excision of residual endometriosis may be effective and should be considered.” (Clayton et al., 1999)

- “A high recurrence rate of 62% is reported in advanced stages of endometriosis in which the ovaries were conserved. Ovarian conservation carries a 6 fold risk of recurrent pain and 8 folds risk of reoperation. The decision has to be weighed taking into consideration the patient’s age and the impact of early menopause on her life style. The recurrence of endometriosis symptoms and pelvic pain are directly correlated to the surgical precision and removal of peritoneal and deeply infiltrated disease. Surgical effort should always aim to eradicate the endometriotic lesions completely to keep the risk of recurrence as low as possible.” (Rizk et al., 2014)

- “We found that among women undergoing hysterectomy, endometriosis was associated with a higher degree of prescription of analgesics. In the endometriosis group the prescription of analgesic, psychoactive and neuroactive drugs did not decrease significantly after surgery. In fact, the prescription of psychoactive and neuroactive drugs increased.” (Brunes et al., 2020)

- “Studies have showed that the growth and progression of endometriosis continue even in ovariectomized animals.” (Khan et al., 2013)

- Read more here: “Endometriosis persisting after hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: Removing the disease, not organs, is key to long-term relief”: http://endopaedia.info/treatment21.html

- “All of your endo will die off in menopause.” Whether natural, surgically induced, or medically induced, there are cases of endometriosis continuing after menopause. Endometriosis lesions are capable of producing their own estrogen (Huhtinen, Ståhle, Perheentupa, & Poutanen, 2012). Another spin off is that “you are too old to have endometriosis”. Inceboz (2015) reports cases of endometriosis in the 8th and 9th decade of life. While some people’s symptoms do improve, it is not a sure thing.

- “As an estrogen-dependent disease, endometriosis was thought to become less active or regress with the onset of the menopause. However, based on some new data, we are discovering that this pathology can emerge or reappear at this period of life.” (Marie-Scemama, Even, De La Joliniere, & Ayoubi, 2019)

- “Endometriotic lesions remained biologically active, with proliferative activity and preserved hormonal responsiveness, even in the lower estrogenic environment in the postmenopause.” (Inceboz, 2015)

- “True prevalence of postmenopausal endometriosis is unknown. There have been some reports in the literature on the prevalence of endometriosis in postmenopausal women [5–8]. According to these studies, the prevalence of postmenopausal endometriosis is 2–5%…. Interestingly, nine of the cases were at the upper extreme of the age groups (eight were in 80–85 years and a case in 90–95 years).” (Inceboz, 2015)

- “Occurrence or progression of postmenopausal endometriosis lesions could be related to extra-ovarian production of estrogen by endometriosis lesions and adipose tissue, which becomes the major estrogen-producing tissue after menopause. Postmenopausal women with symptomatic endometriosis should be managed surgically…” (Streuli, Gaitzsch, Wenger, & Petignat, 2017)

- “Getting pregnant will help.” However, endometriosis can cause infertility…..

- “Although gynaecologists often advise women that pregnancy has a beneficial effect on endometriosis, few studies confirm this association. Owing to the paucity and limited quality of the data, we can conclude that the behaviour of endometriotic lesions during pregnancy seems to be variable, ranging from complete disappearance to increased growth. Despite some of the early authors questioning a positive effect (McArthur and Ulfelder, 1965; Schenken et al., 1987), the idea to recommend pregnancy as part of the treatment strategy for endometriosis persists to this day (Rubegni et al., 2003; Coccia et al., 2012; Benaglia et al., 2013). The few favourable early observations and very limited options to treat endometriosis seem to have generated the myth of a beneficial effect of pregnancy and initiation of the so-called ‘pseudopregnancy’ therapy. Endometriosis is associated with infertility, and a lower prevalence of endometriosis in pregnant than in non-pregnant women may have led clinicians and scientists to the view that pregnancy has a positive effect against the disease.” (Leeners, Damaso, Ochsenbein-Kölble, & Farquhar, 2018)

- “Mild endometriosis won’t affect fertility.” So-called “mild” or “minimal” endometriosis can affect the ability to conceive (Carvalho et al., 2012). Also, “mild” or “minimal” endometriosis can still produce significant symptoms (see Pain with Minimal Endometriosis).

- “The purpose of this systematic review is to present studies regarding the association between pregnancy rates and the presence of early stages of endometriosis. Studies regarding infertility, minimal (stage I, American Society of Reproductive Medicine [ASRM]) and mild (stage II, ASRM) endometriosis were identified…Earlier stages of endometriosis play a critical role in infertility, and most likely negatively impact pregnancy outcomes.” (Carvalho, Below, Abrão, & Agarwal, 2012)

- “Hormonal suppressants will clean up the rest of the endometriosis.” Hormonal medications may be useful for other problems but cannot be relied upon to “clean up” or prevent recurrence of endometriosis. Surgeons who perform endometriosis surgery exclusively (excision) versus a general gynecological/obstetric practice have more chance to develop skill in being able to identify and being able to remove ALL endometriosis lesions (Khazali, 2020) (see Why Excision is Recommended).

- “Endometriotic stromal cells resist the antiproliferative effect of GnRH agonists and antagonists.” (Taniguchi et al., 2013)

- “This case demonstrates the obvious progression of deep rectal endometriosis despite 4 years of continuous hormonal therapy.” (Millochau et al., 2016)

- “Few studies of medical therapies for endometriosis report outcomes that are relevant to patients, and many women gain only limited or intermittent benefit from treatment.” (Becker et al., 2017)

- “There is currently no evidence to support any treatment being recommended to prevent the recurrence of endometriosis following conservative surgery.” (Sanghera et al., 2016)

- “A systematic review found that post-surgical hormonal treatment of endometriosis compared with surgery alone has no benefit for the outcomes of pain or pregnancy rates, but a significant improvement in disease recurrence in terms of decrease in rAFS score (mean = −2.30; 95% CI = −4.02 to −0.58) (Yap et al., 2004). Overall, however, it found that there is insufficient evidence to conclude that hormonal suppression in association with surgery for endometriosis is associated with a significant benefit with regard to any of the outcomes identified….Moreover, even if post-operation medication proves to be effective in reducing recurrence risk, it is questionable that ‘all’ patients would require such medication in order to reduce the risk of recurrence.” (Guo, 2009)

- “Many studies have investigated factors determining the recurrence of endometrioma and pain after surgery [16, 19, 20]…. Regardless of the mechanism, the present and previous studies suggest that postoperative medical treatment is known to delay but not completely prevent recurrence…. In our study, we also failed to observe a benefit for postoperative medication in preventing endometrioma and/or endometriosis-related pain recurrence.” (Li et al., 2019)

- “Furthermore, all currently approved drugs are suppressive and not curative. For example, creating a hormonal balance in patients by taking oral contraceptives, such as progestins and gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonists, may only relieve the associated inflammatory status and pain symptoms.” (Che et al., 2015)

- “If I respond to hormonal therapy then that means I have endometriosis.” Response to hormonal treatment, whether positive or negative, does NOT diagnose endometriosis or exclude it.

- “Relief of chronic pelvic pain symptoms, or lack of response, with preoperative hormonal therapy is not an accurate predictor of presence or absence of histologically confirmed endometriosis at laparoscopy.” (Jenkins, Liu, & White, 2008)

- “The definitive diagnosis of endometriosis can only be made by histopathology showing endometrial glands and stroma with varying degree of inflammation and fibrosis.” (Rafique & Decherney, 2017)

- “My scans didn’t show anything so I was told I didn’t have endometriosis.” Transvaginal ultrasounds and magnetic resonance imaging are becoming more sensitive in the hands of those with experience and can rule in instances of endometriosis (especially deep infiltrating endometriosis and endometriomas). However, it cannot rule out endometriosis. (See But All Your Tests Are Negative)

- “Currently, there are no non‐invasive tests available in clinical practice to accurately diagnose endometriosis…. Laparoscopy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis and using any non‐invasive tests should only be undertaken in a research setting.” (Nisenblat et al., 2016)

- “Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging can be used to diagnose ovarian endometriotic cysts and deep infiltrating endometriosis; but their performance is poor in the diagnosis of initial stages of endometriosis.” (Ferrero, 2019)

- “None of my tests showed I had endometriosis.” Other tests, in addition to scans, cannot adequately rule out endometriosis with consistency or certainty.

- “Currently, there are no non‐invasive tests available in clinical practice to accurately diagnose endometriosis…. Laparoscopy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis and using any non‐invasive tests should only be undertaken in a research setting.” (Nisenblat et al., 2016)

- “CA‐125 and other serum markers (such as CA 19‐9, serum protein PP14, interleukins, and angiogenetic factors) have been measured in women with endometriosis but they are not reliable for the diagnosis of the disease.” (Ferrero, 2019)

- “The majority of studies focused on a panel of biomarkers, rather than a single biomarker and were unable to identify a single biomolecule or a panel of biomarkers with sufficient specificity and sensitivity in endometriosis. Conclusion: Noninvasive biomarkers, proteomics, genomics, and miRNA microarray may aid the diagnosis, but further research on larger datasets along with a better understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms are needed.” (Anastasiu et al., 2020)

- “I was told I had IBS.”

- “Endometriosis can be commonly misdiagnosed as IBS [22] due to overlap in common symptoms and perhaps mechanisms of disease progression involving aberrant activation of inflammatory cascades.” (Torres-Reverón, Rivera-Lopez, Flores, & Appleyard, 2018)

- “You are too young to have endometriosis.” Or “you are too young to have adenomyosis or DIE.” In those adolescents with chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis is a common discovery. Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) can be found in teens.

- “Endometriosis is a common finding in adolescents who have a history of chronic pelvic pain or dysmenorrhoea resistant to medical treatment, however the exact prevalence is unknown. Both early/superficial and advanced forms of endometriosis are found in adolescents, including ovarian endometriomas and deep endometriotic lesions. Whilst spontaneous resolution is possible, recent reports suggest that adolescent endometriosis can be a progressive condition, at least in a significant proportion of cases. It is also claimed that deep endometriosis has its roots in adolescence.” (Sarıdoğan, 2017)

- “The majority of adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain not responding to conventional medical therapy have endometriosis (up to 80%). Laparoscopy with biopsy is the only way to diagnose endometriosis in the adolescent population, and depends on recognition of atypical manifestations of the disease.” (Yeung Jr, Gupta, & Gieg, 2017)

- “Adolescent endometriosis is not a rare condition.” (Audebert et al., 2015)

- “An increasing body of literature suggests that advanced-stage endometriosis (revised scoring system of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Stage III or IV) and deeply invasive endometriosis are relatively common in adolescents.” (Dowlut-McElroy & Strickland, 2017)

- “In all, 648 of 1011 (64%) adolescents undergoing laparoscopy were found to have endometriosis. The prevalence ranged from 25% to 100%, with a mean prevalence of 64%. Thirteen studies including 381 participants categorized disease severity using the revised American Society of Reproductive Medicine classification. Among these, 53% of participants (201/381) had stage I, 28% (105/381) had stage II, 20% (76/381) had stage III, and 13% (49/381) had stage IV disease. Conclusions: The prevalence of endometriosis among adolescents with pelvic pain symptoms is high. Endometriosis is treatable, and prompt recognition will help to ensure that adolescents are signposted earlier to appropriate specialists. The management of adolescents with suspected endometriosis should be consistent with best practice guidance. Despite recommendations to increase the awareness and knowledge of endometriosis in adolescence, minimal research has followed.” (Hirsch et al., 2020)

- “My endo keeps coming back so there’s nothing I can do.” It can be difficult to ascertain if endometriosis truly reappeared or was all of it not removed previously (See Is There Microscopic or Occult Endometriosis). With repetitive surgeries or with endometriosis in certain locations (such as ureters, bowel, diaphragm, etc.), seeking someone who exclusively does surgery for endometriosis and its related conditions can be beneficial (Khazali, 2020). Often a team approach, utilizing other specialties as dictated by the individual’s case, is valuable (Khazali, 2020). (See Why Excision is Recommended) Recurrence can happen, more often in ovarian endometriosis, stage III and IV, and in those who were younger (Selçuk & Bozdağ, 2013). When looking at recurrence rates, it ranges from 6% to 67% (Selçuk & Bozdağ, 2013)! This wide range is due to many factors when evaluating studies- most studies do not differentiate the type of surgery, the type of surgeon (specialty center versus general gynecological practice), or the criteria for recurrence (was it reemergence of symptoms or repeat surgery) (Selçuk & Bozdağ, 2013). There are many related conditions that appear with endometriosis that can cause similar symptoms that should also be addressed (See Related Conditions).

- “A multidisciplinary team approach (eg, gynecologic endoscopist, colorectal surgeon, urologist) can reduce risk and facilitate effective treatment.19 Likewise, advanced surgical skills and anatomical knowledge are required for deep resection and should be performed primarily in tertiary referral centers. Careful preoperative planning, informed consent, and meticulous adherence to “best practice” technique is requisite to reduce morbidity and ensure effective management of potential complications.90Although excisional biopsy and resection offers a higher success rate in treating the disease, surgical excision also requires a higher level of surgical skill. As a result, many patients receive incomplete treatment, which in turn may lead to persistent symptoms and recurrent disease. It should be noted that many women who have undergone repeated surgeries and had a hysterectomy still suffer.86 The need to improve surgical approach and/or engage in timely referrals is unquestionable. Surgery to debulk and excise endometriosis may be “more difficult than for cancer”. Complete removal of implants may be difficult due to variation in appearance and visibility. True surgical resection and treatment poses formidable challenges, even the hands of experienced clinicians. In particular, deep disease is often difficult to treat due to close proximity of and common infiltration in and around bowel, ureters, and uterine artery.18 Potential adenomyosis should also be included in the preoperative workup, as it can influence postoperative improvement patterns of pain and symptoms associated with endometriosis.” (Fishcer et al., 2013)

- “All of the studies were conducted by expert laparoscopic surgeons, whose results are unlikely to be reproduced by the generalist surgeon…. Based on the studies performed to date, it is the author’s opinion that laparoscopic excision of endometriosis, when technically feasible, should be the standard of care. First, whereas visual diagnosis of endometriosis is correct in only 57% to 72% of cases, excisional surgery yields specimens for histologic confirmation—and identifies endometriosis in 25% of “atypical” pelvic lesions as well.18 The availability of such specimens would prevent unnecessary treatment and ensure more reproducible research findings. Excision should also reduce the incidence of persistent disease secondary to inadequate “tip of the iceberg” destruction, removing both invasive and microscopic endometriosis to provide the best possible symptom relief.” (Jenkins, 2009)

- “Laparoscopic identification of superficial endometriosis implants represents a challenge for the gynecologic surgeon. Endometriosis lesions may present in a wide spectrum of appearance according to a “lifecycle” of the implants. The lesions can be flat or vesicular. They can have any combination of color typically red, back/brown and white. Active “red” lesions, large endometriomas, deep infiltrating nodules, and typical “powder-burn” lesions are easier to identify than “white” old fibrotic lesions. The endometriotic implants are hypervascular. The diagnostic accuracy at laparoscopy is also affected by the experience of the surgeon and the laparoscopic equipment [16].” (Jose, Fausto, & Antonio, 2018)

- “It’s all in your head.” When no visible cause is identified or usual treatments fail, the blame often gets shifted to the individual- that they are exaggerating or are not strong enough to deal with it or that they should be able to just live it. Sadly, one study (Rowe & Quinlivan, 2020) found that often a women’s fertility rather than quality of life was the driver for getting further care.

- “Women’s symptoms are frequently trivialized or disbelieved, consequently attributing pathology to the woman rather than the disease, which is deeply distressing [11]. These responses are underpinned by essentialist notions that pain is just part of being a woman. Lack of legitimation results in victim blaming, reinforces gendered stereotypes about feminine weakness, intensifies women’s distress and averts prompt action [10]. Similar essentialist ideas underlie observations that framing endometriosis as a fertility problem is more likely to result in health care intervention than when it is framed as symptom management. In one qualitative study, women described fertility as the entry point for discussion about endometriosis, despite having sought health care for symptoms over many years [12].” (Rowe & Quinlivan, 2020)

- “Endometriosis impairs the quality of life due to chronic and severe acyclic pelvic pain with associated dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, gastrointestinal problems, fatigue and headaches….women with endometriosis are often surrounded by taboos, myths, scourge of subfertility, pain of disease and missed diagnosis and treatment [22]. Delays in the diagnosis and initiation of treatment for the disease in fact occur due to these counterproductive factors operative both at the individual patient level and at the medical level resulting in frustration and loss of valuable time in the prime phase of life of the patient….Delays also occur at the medical level due to the delay in referral from primary to secondary care, pain normalized by clinicians, intermittent hormonal suppression of symptoms, use of non-discriminating investigations and insufficiency in awareness and lack of constructive support among a subset of healthcare providers [23,24,25,37,38]. In this connection, it is noteworthy that delay in diagnosis is longer for women reporting with pelvic pain compared with those reporting with infertility, which is suggestive of the fact that there is a higher level of reluctance surrounding endometriosis-associated pain symptoms….” (Ghosh et al., 2020)

- “Women had to ‘battle’ for an accurate diagnosis, and had limited faith in health professionals…. Conclusions: Implications for health professionals are discussed, including the need for earlier diagnosis and taking women’s symptoms more seriously at referral…” (Grogan, Turley, & Cole, 2018)

- “Despite its high prevalence and cost, endometriosis remains underfunded and underresearched, greatly limiting our understanding of the disease and slowing much-needed innovation in diagnostic and treatment options. Due in part to the societal normalization of women’s pain and stigma around menstrual issues…” (As-Sanie et al., 2019)

References: https://icarebetter.com/red-flags/

Labwork and Blood Tests for Endometriosis

While several companies are working to develop one, there is no single blood test that can definitively diagnose endometriosis yet. It takes a long time to determine if a test has the reliability “so that no patients with actual endometriosis would be missed and no women without endometriosis would be selected for potentially unnecessary additional procedures” (Signorile & Baldi, 2018). Fassbender et al. (2015) notes that such tests might help receive a diagnosis more quickly so that “no women with endometriosis or other significant pelvic pathology are missed who might benefit from surgery for endometriosis associated pain and/or infertility”.

In our Diagnosis section, you can read more about some of the types of blood tests that are under investigation. Other blood tests can be used to rule out other problems and can give an indication to investigate further but are not specific to endometriosis (such as CRP and CA-125). You can also find information in the Diagnosis section about the use of ultrasounds and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI’s) in endometriosis.

“The gold standard for the diagnosis of peritoneal endometriosis has been visual inspection by laparoscopy followed by histological confirmation [7].However, the invasive nature of surgery, coupled with the lack of a laboratory biomarker for the disease, results in a mean latency of 7–11 years from onset of symptoms to definitive diagnosis. Unfortunately, the delay in diagnosis may have significant consequences in terms of disease progression. The discovery of a sufficiently sensitive and specific biomarker for the nonsurgical detection of endometriosis promises earlier diagnosis and prevention of deleterious sequelae and represents a clear research priority….The most important goal of the test is that no women with endometriosis or other significant pelvic pathology are missed who might benefit from surgery for endometriosis-associated pain and/or infertility [17–19].”

(Fassbender et al., 2015, para. 1, 5)

Before and after surgery- tips on preparing

We get a lot of questions about what to expect before and after surgery. On our Resources page, we have added a section on Preparing for Surgery- Pre and Post-Operative.

In the Before Surgery section, you’ll find links to topics such as:

In the After Surgery section, you’ll find topics such as:

- What to Expect in the Weeks After Skilled Excision Surgery

- Managing Expectations Pre- and Post- Op

- Pelvic Therapy Resources

Another often asked question is whether your endo is “coming back” or persisting after surgery. This is a complicated question, but this might help:

Check out the Resources page for more information!

Migraines- overlap of common conditions or close tie to endo?

Both migraines and endometriosis affect a high percentage of the population. Endometriosis affects about 10-15% of the population, while migraines affect >12% of the population (Parasar, Ozcan, & Terry, 2017; Yeh, Blizzard, & Taylor, 2018). So is any association between the two just an overlap of two common conditions? Or is there something that ties the two together?

According to several studies, there is a higher prevalence of migraines in people with endometriosis. One study noted that “the risk of endometriosis was significantly higher in migrainous women” and that “women of reproductive age who suffer from migraine should be screened for endometriosis criteria” (Maitrot-Mantelet et al., 2020). Another study noted a “linear relationship exists between migraine pain severity and the odds of endometriosis” (Miller et al., 2018). One study also attempted to account for the effects of hormones on migraines and endometriosis and found evidence of a “co-morbid relationship between migraine and endometriosis, even after adjusting for the possible effects of female hormone therapies on migraine attacks” (Yang et al., 2012).

Curious about other related conditions? Check out Related Conditions

Bowel Endometriosis Surgical Management

While many individuals have bowel/gastrointestinal symptoms with endometriosis (like diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and pain with defecation), most will not have endometriosis directly on the bowel itself. (See more on bowel endometriosis here). For those that do, there are different approaches to its surgical management.

The different approaches might include shaving, excision, and resection. Studies reveal the advantages and disadvantages of the different techniques- you can read some of those studies here. Most experts express using a team approach (such as involving a colorectal surgeon), using imaging to help guide planning before surgery (with preference for MRI), and decisions based on each individual. Those with more advanced skill in working with bowel endometriosis cite low complication rates. (You can find more on the experts’ opinions in Nancy’s Nook Facebook Group in Unit 2: Surgery).

Genetics of endometriosis: what are the risks?

Is there a genetic component to endometriosis? According to various studies, there is. (You can find links to several of these studies, including the ones below, in Origin Theories of Endometriosis.) This past week someone asked if there is an increased risk if there is a family history on your father’s side. According to this study, there is a “definite kinship factor with maternal and paternal inheritance contributing”.

Another often asked question is how strong is the risk associated within families. According to one study, there is an estimated 5.2 increased risk between sisters and a 1.6 increased risk in cousins. The study also stated that among twins, there was a 51% increased risk. Another study indicated that there is a “sixfold increased risk for first-degree relatives of women with laparoscopically confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis”. Another study indicates a “first-degree relatives of affected women are 5 to 7 times more likely to have surgically confirmed disease”. Yet another study indicated that there is a stronger association with genetic risk for “severe” disease versus “minimal” or “moderate”. (Remember that disease severity in staging is based on the anatomy affected and fertility not necessarily the severity of symptoms- see more about that here.)

While this doesn’t mean a relative will definitely have endometriosis just because you do, it does indicate an increased risk, especially for first degree relatives. There are several genes noted to be involved in endometriosis and several mechanisms on how those genes are expressed in endometriosis. While these studies are paving the way to understanding endometriosis, there is still much to be learned.

What does endometriosis look like? And tips on coping with endometriosis

When looking at endometriosis, it is important to know what it looks like, where it is found, and how it functions. This can affect treatment by knowing how medications may or may not affect it and how surgeons can effectively remove it (by knowing its appearance and where to look for it). This week we added the Many Appearances of Endo and Histology of Endometriosis (what it looks like under a microscope) in order to help you understand what endometriosis looks like. More information about the basics of endometriosis can be found in What Is Endometriosis?.

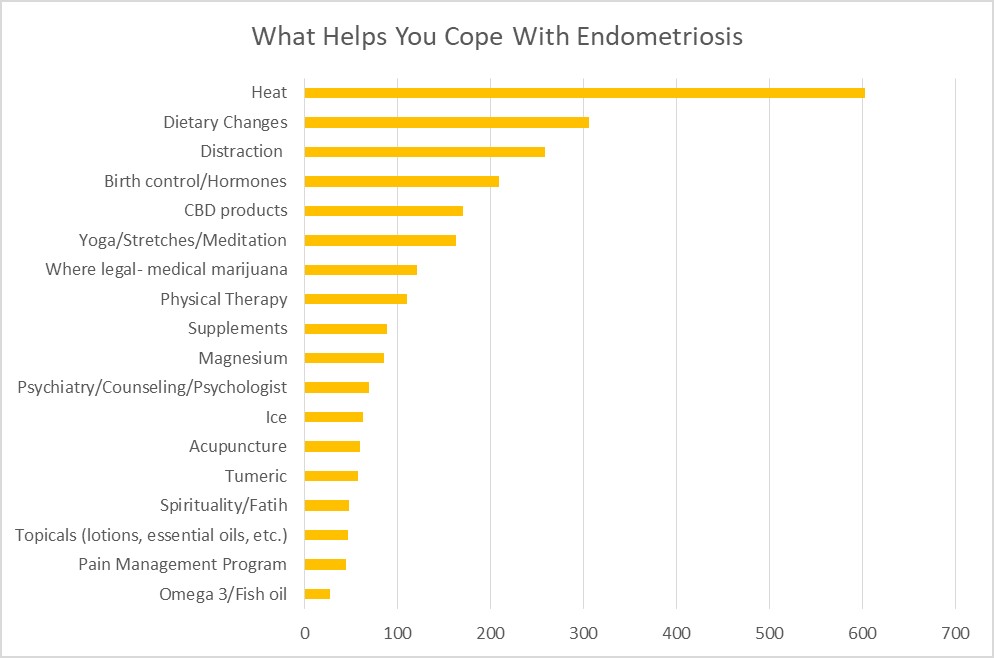

One question that often arises in Nancy’s Nook Facebook group is how to cope with endometriosis while seeking effective treatment. Who better to ask than those who have endometriosis? Several members of the group noted several things that helped them to cope. To date, the most utilized were heat, dietary changes, and distraction. Find out what additional things helped others with endometriosis in Coping with Endometriosis.