Can Endometriosis Cause Vomiting?

Table of contents

A Perplexing Condition

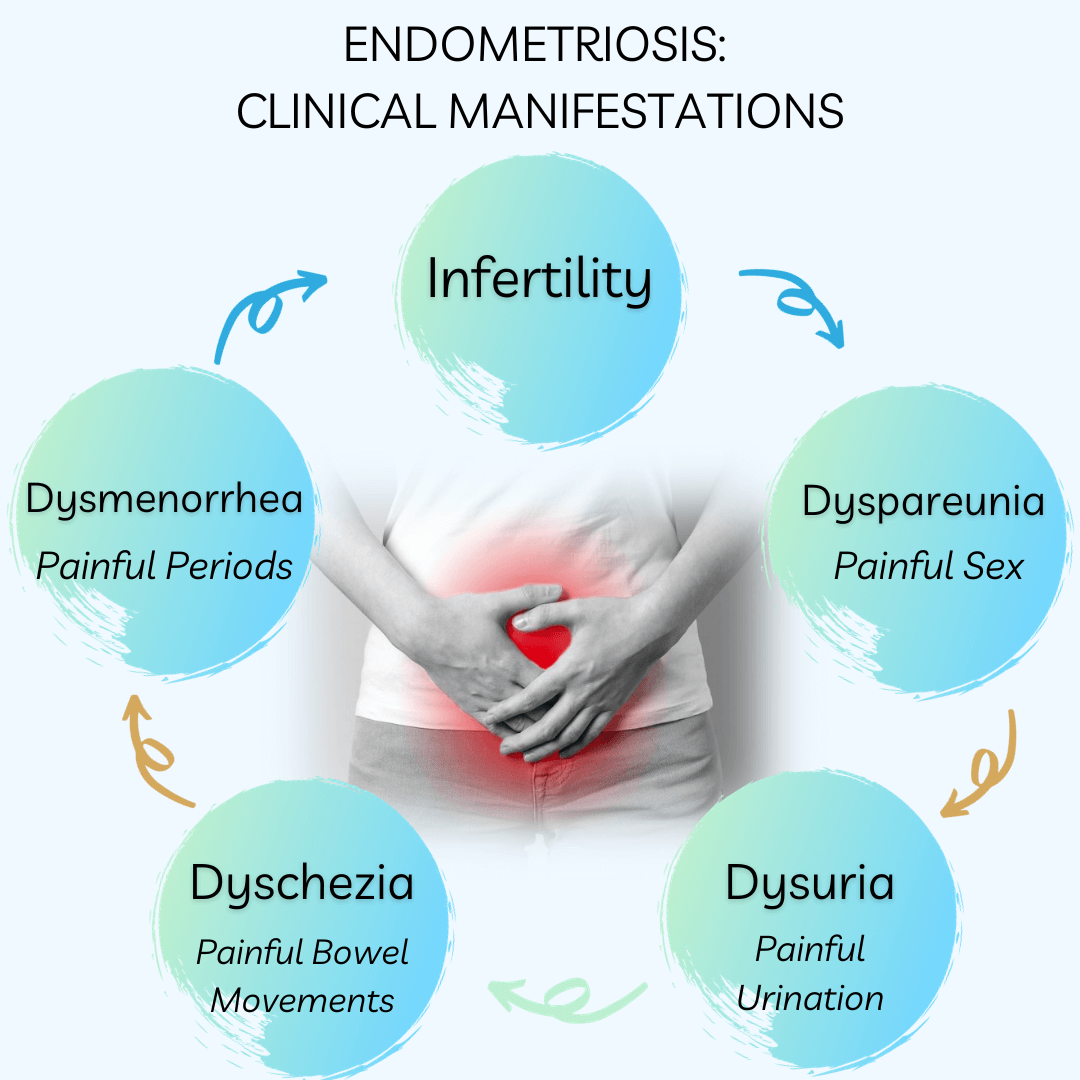

Endometriosis, a disorder affecting an estimated 176 million women worldwide, is characterized by the abnormal growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. While pelvic pain and infertility are well-recognized symptoms, many individuals remain unaware of the connection between endometriosis and gastrointestinal issues, including vomiting.

The Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Contrary to popular belief, gastrointestinal symptoms are nearly as prevalent as gynecological symptoms in women with endometriosis. Interestingly, 90% of patients with this illness initially have gastrointestinal issues such as bloating, diarrhea, constipation, uncomfortable bowel movements, nausea, or vomiting.

Bloating: A Persistent Symptom

Bloating is the most often reported symptom, impacting an astounding 83% of endometriosis-affected women. The ongoing discomfort could significantly affect everyday activities and the general quality of life.

Vomiting and Nausea: The Often Ignored Symptoms

Despite occasionally taking center stage, nausea and vomiting are unpleasant symptoms that can significantly affect people with endometriosis. These symptoms may point to a complex interaction between the disease and gastrointestinal function, regardless of where the endometrial lesions are located in relation to the colon. Additionally, vomiting and nausea can result from severe pain and discomfort.

The Link Between Endometriosis and IBS

To make matters worse, endometriosis can mimic symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), such as frequent bloating and irregular bowel movements. When seeking assistance from a gastroenterologist, many women receive an IBS diagnosis before identifying the underlying endometriosis.

This is typical: A young woman visits a gastroenterologist due to bloating and constipation. She was diagnosed with IBS following an upper endoscopy and colonoscopy that showed no visible digestive problems. Her IBS symptoms do not go away, though, because endometriosis is the underlying cause of them.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

There is a common link between endometriosis and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), a disorder marked by a notable build-up of bacteria in the small intestine. As a result of this overgrowth, patients with endometriosis may have more severe digestive issues, such as bloating, gas, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

The lactulose-hydrogen breath test measures the amounts of hydrogen and methane in the breath. It is a straightforward, noninvasive, and reasonably priced method of diagnosing SIBO.

Strategies for Treatment

Although there is currently no recognized treatment for endometriosis, there are several ways to help control symptoms, including nausea and vomiting:

- Surgical Intervention: Laparoscopic excision surgery can reduce symptoms by treating the underlying cause by removing endometriosis tissue.

- Hormonal Medications and Contraceptives: Hormonal therapy can lessen symptoms.

- Pain Management: Physicians may recommend over-the-counter pain relievers to patients to alleviate the discomfort associated with endometriosis and gastrointestinal issues.

- SIBO Treatment: Medication alone is not enough to reduce gastrointestinal issues associated with endometriosis; lifestyle modifications are also helpful.

Seeking Professional Guidance

You should consult a physician if you experience nausea, vomiting, or severe abdominal discomfort regularly. A thorough assessment that involves imaging scans, a laparoscopy, and a pelvic examination may be required to get an accurate diagnosis and develop a care plan.

The Value of Prompt Intervention

If endometriosis is not treated, it can have a major negative impact on a person’s quality of life. Recognizing and seeking care for gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting as soon as possible might help people’s chances of receiving treatment and managing their symptoms.

Conclusion

Beyond infertility and pelvic pain, endometriosis is a complex disease. People can increase their chances of receiving treatment and managing their symptoms by recognizing and obtaining care for gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea and vomiting as soon as possible. Women with endometriosis can improve their overall quality of life and take back control of their lives by using a multidisciplinary strategy that includes lifestyle changes, medicinal therapies, and support networks.

REFERENCES:

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/endometriosis-and-nausea

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4535676

Understanding Endometriosis and Stomach Cramps

Endometriosis is a medical condition that affects approximately 10% of women globally. Its symptoms can be debilitating and significantly impact the quality of life of those affected. One of the most commonly reported symptoms of endometriosis is stomach cramps. This article delves into the relationship between endometriosis and stomach cramps, unraveling the causes, symptoms, and available treatment options.

Table of contents

What is Endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a health disorder that occurs when tissue similar to the uterus’s endometrium begins to grow in areas outside the uterus. These areas may include the ovaries, fallopian tubes, the lining of the pelvic cavity, and, in some cases, the bowels and bladder.

What is Endo Belly?

One term that has gained popularity in endometriosis discussions is “endo belly.” This term refers to the painful abdominal bloating often associated with endometriosis. The bloating, which can be severe, results from inflammation, growths, gas, or other digestive issues related to endometriosis.

Causes of Endo Belly

The exact cause of endo belly still needs to be fully understood. However, several factors have impacted this symptom. The endometrial-like tissue behaves similarly to the endometrium: it thickens, breaks down, and bleeds with each menstrual cycle. However, since this tissue cannot exit the body, it becomes trapped, leading to inflammation and irritation. Over time, this can cause scar tissue to form, leading to various symptoms, including bloating and fluid retention.

Symptoms of Endo Belly

The primary symptom of endo belly is severe bloating, particularly during or just before the menstrual period. The abdomen may fill with air or gas, causing it to appear larger and feel stiff or tight to the touch. This bloating may last for a few hours to a few weeks. Other symptoms that may accompany endo belly include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Gas pain

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Abdominal discomfort, pain, and pressure

How Endometriosis Causes Stomach Cramps

The stomach cramps associated with endometriosis are often severe and debilitating. These cramps are not merely due to the menstrual cycle but are a direct result of the endometrial-like tissue growing outside the uterus. This tissue resembles the endometrium, building up and breaking down each menstrual cycle. But because this tissue is outside the uterus and cannot exit the body, it gets trapped. This trapped tissue leads to inflammation and irritation, which can cause severe stomach cramps.

Symptoms of Stomach Cramps Due to Endometriosis

The main symptom associated with endometriosis-induced stomach cramps is severe pain, particularly during the menstrual period. This pain can be so intense that it disrupts daily activities and significantly impairs the individual’s quality of life. The pain often worsens throughout the day and can be so severe that the person may not be able to button their pants or may even appear as though they are pregnant.

Treatment for Endometriosis and Stomach Cramps

There are several treatment options available for managing endometriosis and its associated stomach cramps. Treatment choice often depends on the severity of the symptoms, the person’s age, and their future pregnancy plans. The treatment options include:

- Over-the-counter Medications: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or aspirin, may be recommended to manage inflammation and reduce pain.

- Prescription Hormonal Medications: Hormonal pills or devices may help to regulate symptoms.

- Endometriosis Surgery: In severe cases, surgery may be the best option for long-term pain relief. This surgery involves removing the endometriosis and scar tissue from the pelvic and abdominal organs.

When to Consult a Doctor

It’s essential to consult an endo specialist if you’re experiencing severe stomach cramps, mainly if they’re associated with your menstrual cycle. Early diagnosis and treatment can significantly improve your quality of life and prevent potential complications, such as infertility.

Conclusion

Endometriosis and stomach cramps are closely linked. The condition can lead to severe stomach cramps that can significantly impair the quality of life of those affected. However, you can manage the symptoms effectively with proper diagnosis and treatment. Suppose you’re experiencing severe stomach cramps, especially if they’re associated with your menstrual cycle. In that case, it’s essential to consult a healthcare provider for a proper diagnosis and treatment plan.

References:

https://maidenmedical.com/endometriosis-belly

https://www.healthline.com/health/endo-belly

https://www.endofound.org/gastrointestinal-distress

https://www.utphysicians.com/the-pain-of-endometriosis/

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/endo-belly

Does Endometriosis Cause Bowel Problems

Endometriosis, a chronic medical condition that affects up to 10% of women worldwide, has a significant impact on various aspects of a woman’s life, including her bowel health. This article will explore the question:

“Does endometriosis cause bowel problems?”

and delve into the symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment of this condition.

Table of contents

- What is Endometriosis?

- Endometriosis and Bowel Problems

- Recognizing the Symptoms

- Bowel Endometriosis: Causes and Risk Factors

- Diagnosing Bowel Endometriosis

- Treatment Options for Bowel Endometriosis

- Post-Surgery Recovery and Follow-up

- The Impact of Delayed Treatment

- The Importance of Specialist Care

- Conclusion

What is Endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a medical condition in which tissue resembling the endometrium, the lining of the uterus, grows outside of the uterus. This tissue can grow on various organs, including the ovaries, fallopian tubes, bladder, and even the bowel.

Endometriosis and Bowel Problems

Endometriosis can affect the bowel in various ways, leading to numerous digestive issues. Specifically, endometriosis can grow on or inside the bowel walls, causing symptoms that are often mistaken for other conditions like Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

Superficial and Deep Bowel Endometriosis

Bowel endometriosis can present in two forms:

- Superficial Bowel Endometriosis: This is when endometriosis is found on the surface of the bowel.

- Deep Bowel Endometriosis: This form of endometriosis penetrates the bowel wall.

In some cases, rectovaginal nodules can start as superficial endometriosis and progress to infiltrate the bowel wall.

Read More: Can Endometriosis Cause Bowel Issues?

Recognizing the Symptoms

The symptoms of bowel endometriosis are similar to those of IBS. However, they can vary with the menstrual cycle, worsening in the days before and during a period. Some common symptoms include:

- Pain with defecation (dyschezia)

- Deep pelvic pain during sex (dyspareunia)

- Rectal bleeding during a period

If you experience these symptoms, it’s crucial to discuss them with your doctor. They may choose to use several techniques for diagnosis, such as a vaginal examination, ultrasound, sigmoidoscopy, laparoscopy, CT, or MRI scan.

Bowel Endometriosis: Causes and Risk Factors

While the definitive cause of endometriosis remains unknown, several potential contributing factors include hormonal imbalances, immune system problems, and genetic factors. Researchers have also found links to genes and stem cells, inflammation, and estrogen levels.

Read More: What Does Bowel Endometriosis Feel Like? Understanding the Pain and Symptoms

Diagnosing Bowel Endometriosis

Diagnosing bowel endometriosis can be challenging due to its similarities with other conditions like IBS. In addition to a physical examination and medical history review, doctors may suggest imaging tests such as transvaginal or transrectal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), laparoscopy, or barium enema.

Treatment Options for Bowel Endometriosis

The treatment for bowel endometriosis typically involves a combination of painkillers, hormone treatments, and surgeries, depending on the severity of the symptoms. Surgery is usually recommended for bowel endometriosis, with the surgical options varying based on the severity of the condition and the areas affected.

There are three main surgery options for bowel endometriosis:

- The affected segment of the bowel is removed, and the bowel is rejoined (re-anastomosis).

- For smaller areas of endometriosis, the disc of affected bowel is cut away, followed by the closure of the hole in the bowel.

- Affected areas can be “shaved” off the bowel, leaving the bowel intact.

Post-Surgery Recovery and Follow-up

Recovery after any surgery varies depending on the individual. After laparoscopic bowel surgery, you can generally expect to go home within four days. Bowel function may be altered after surgery, particularly with a full resection (re-anastomosis). This does improve over time, although watching your diet to see which food aggravate or improve the situation may be helpful.

The Impact of Delayed Treatment

If bowel endometriosis is not treated properly and promptly, the disease may progress, and quality of life significantly decreases. Small lesions on the bowel can eventually progress and become full-thickness lesions that cause obstruction and may require major bowel surgery.

The Importance of Specialist Care

Because bowel endometriosis deals with your gastrointestinal system, it’s usually not solely treated by a general gynecologist. A collaborative care approach between an endometriosis expert, gastroenterologist, and/or general surgeon may be necessary to treat your bowel endometriosis from all angles.

Read More: Finding an Excision Specialist: What you Need to Know

Conclusion

Understanding the link between endometriosis and bowel problems is vital for improving diagnosis and treatment outcomes. If you’re experiencing symptoms of bowel endometriosis, it’s important to discuss them with your doctor and consider seeing a specialist. In doing so, you’ll be taking an important step towards managing your symptoms and improving your quality of life.

References:

https://www.endometriosis-uk.org/endometriosis-and-bowel

https://www.webmd.com/women/endometriosis/bowel-endometriosis

https://www.everydayhealth.com/endometriosis/bowel-endometriosis/

Endometriosis and constipation

https://drseckin.com/bowel-endometriosis/

Can Ureteral Endometriosis Cause Kidney Shooting Back Pain?

Endometriosis is a common gynecological condition that affects many women during their reproductive years. While it typically manifests in the pelvic region, in some instances, it may invade other organs, including the urinary system. This article explores the question: Can endometriosis on the ureter cause kidney shooting back pain?

Table of contents

About Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a chronic disease characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the womb. This could include the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and the lining of the pelvic cavity. In some extreme cases, endometrial tissue may also affect organs outside the pelvic cavity, such as the bladder, bowel, or kidneys.

Read More: Understanding Endometriosis: Unveiling the Common Symptoms and Their Impact

Understanding Ureteral Endometriosis

Ureteral endometriosis is an uncommon manifestation of the disease, accounting for about 1% of all endometriosis cases. It involves the ureters, the tubes that transport urine from the kidneys to the bladder. This condition can lead to urinary tract obstruction, resulting in hydronephrosis, which is the swelling of a kidney due to a build-up of urine.

The Kidney-Endometriosis Connection

The kidneys can be impacted when one or both of the ureters become affected by endometriosis. The section of the ureter that is usually affected sits below the pelvic area.

Symptoms of Kidney Endometriosis

Kidney endometriosis can be asymptomatic for several years. If a person who has undergone surgery to treat endometriosis has ongoing urinary problems such as pain and infections, it may suggest the presence of urinary tract or kidney endometriosis. Symptoms may include:

- Pain in the lower back that gets worse with a monthly menstrual cycle. That pain can also extend down through the legs.

- Blood in the urine that can co-occur with the menstrual cycle

- Difficulty urinating

- Recurrent urinary tract infections

Read More: Understanding How Endometriosis Can Cause

Diagnosis of Ureteral Endometriosis

The diagnosis of ureteral endometriosis relies heavily on clinical suspicion. As a result, they often misdiagnose patients with kidney cancer. This can lead to patients not receiving treatment on time, or receiving the wrong kind of treatment.

Read More: Life After Endometriosis Surgery: A Comprehensive Guide

Treatment Options

Kidney endometriosis can lead to kidney damage and even kidney failure if left untreated. However, the best approach is to treat the condition by removing endometriosis lesions with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery.

The Silent Threat of Kidney Failure

One of the most concerning aspects of ureteral endometriosis is the silent threat of kidney failure. It is estimated that as many as 25% to 50% of nephrons are lost when there is evidence of ureteral endometriosis, and 30% of patients will have reduced kidney function at the time of diagnosis.

Impact on Kidney Health

The good news is that if one kidney isn’t functioning due to endometriosis, you can survive on the other kidney. So, if you find out you only have one fully-functioning kidney, it’s essential to take care of it.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while endometriosis is typically a pelvic condition, it can venture beyond and affect the urinary system, including the kidneys. This can lead to severe complications, including kidney failure. Therefore, it’s crucial for women with endometriosis to be aware of the potential symptoms and seek medical advice if they experience any signs of kidney problems. The early detection and treatment of ureteral endometriosis are crucial to preserving kidney function and overall health.

References:

https://drseckin.com/kidney-endometriosis/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3535807/

Endometriosis: Perilous impact on kidneys

https://endometriosis.net/clinical/silent-kidney-failure

Understanding the Pain and Symptoms of Bowel Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a condition affecting roughly 11% of women worldwide, predominantly those of reproductive age. An even more specific form of this ailment is bowel endometriosis, which impacts around 5% to 12% of those diagnosed with endometriosis. In this comprehensive guide, we delve into the intricacies of bowel endometriosis, exploring what it feels like, the symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Table of contents

What is Bowel Endometriosis?

Bowel endometriosis occurs when endometrial-like tissue, which typically grows inside the uterus, begins to develop on or inside the bowel walls. This can lead to a range of gastrointestinal symptoms, often causing significant discomfort and negatively impacting the quality of life.

Read More: Understanding Bowel Endometriosis

Where Does Bowel Endometriosis Occur?

The condition predominantly affects the rectum and sigmoid colon, with approximately 90% of bowel endometriosis cases directly involving these regions. However, the appendix, small intestine, stomach, and other parts of the large intestine can also be affected. In many cases, bowel symptoms occur because of the mere presence of intensely inflammatory endo lesions on the peritoneum in the pelvis and abdomen and not even involving the bowel directly with implants.

Symptoms of Bowel Endometriosis

The symptoms of bowel endometriosis often mimic common gastrointestinal disorders, including small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), making it difficult to diagnose. They can range from mild to severe, and often fluctuate depending on the menstrual cycle.

Common Symptoms

Common symptoms may include:

- Abdominal pain, particularly in the lower quadrants

- Bloating, often referred to as “endo belly”

- Changes in bowel movements, including constipation or diarrhea

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pain during bowel movements, which might increase during menstruation

- Rectal bleeding

Non-Bowel Symptoms

In addition to bowel symptoms, individuals with endometriosis might experience:

- Chronic pelvic pain

- Difficulties with fertility

- Painful sexual intercourse

- Pain during urination

- Pelvic heaviness

- Fatigue

- Impaired psychological well-being

Causes of Bowel Endometriosis

The exact cause of bowel endometriosis remains unknown. However, Mullerianosis of embryogenic origin and retrograde menstruation are two often-quoted theories. Mullerianosis of embryogenic origin suggests that developmental abnormalities lead to cells being present in atypical locations which later turn into endometriosis. This includes potential genetic, genomic and immunologic influencing factors. Retrograde menstruation proposes that period blood flows upward towards the Fallopian tubes and into the pelvis instead of out through the vagina, potentially leading to endometriosis. Given that most women experience retrograde menstruation, and only 10% or so experience endometriosis, this theory is antiquated and has been challenged because of this disconnect. Far more likely, some combination of embryologic, molecular, immunologic and genetic factors are in play and this can vary between individuals.

Read More: Can Endometriosis Cause Bowel Issues?

Diagnosis of Bowel Endometriosis

Diagnosing bowel endometriosis is a complex process. It often requires a combination of a good evaluation of symptoms history, physical examination, imaging techniques like ultrasound or MRI, and sometimes minimally invasive laparoscopic or robotic surgery. However, diagnosis could be delayed due to its symptom similarity with other gastrointestinal diseases. Imaging can only help with diagnosis and potential mapping for surgery. It is absolutely not reliable enough to exclude the diagnosis of endo.

Misdiagnosis

Misdiagnosis is common in bowel endometriosis, with many patients being misdiagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or other gastrointestinal disorders. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is necessary for diagnosis, and any bowel symptoms correlated with the menstrual cycle should be critically evaluated.

The Role of Minimally Invasive Surgery

Surgery with biopsy is considered the “gold standard” in diagnosing endometriosis, including bowel endometriosis. It provides a more accurate diagnosis and gives healthcare providers an exact idea of how much scar tissue and endometrial-like tissue they’re dealing with. Ideally, the surgeon should be prepared to perform a therapeutic surgery at the same time as a diagnosis. However, a bad surgery is worse than no surgery if the surgeon is unprepared and performs some variation of fulguration (burning) of endometriosis lesions as opposed to proper excision of the lesions or implants. If diagnostic surgery uncovers a situation where the surgeon is unprepared to properly perform therapeutic excision it is better to back out and refer to an appropriate surgeon.

Treatment of Bowel Endometriosis

Treatment for bowel endometriosis often involves surgery, as medical management has generally been deemed ineffective for these specific lesions. The chosen surgical method depends on the extent of the condition. In many cases, hormonal options may also be recommended after surgery to reduce recurrence risk. The better the surgery the less likely this would be required but there are exceptions.

Surgical Treatment

The surgical treatment of endo usually involves removing all of the peritoneal lesions by an excisional technique. In deeply infiltrating endometriosis, the approach may vary based on the involvement of the rectal wall or the mesentery, which is where the blood vessels to the rectum are located. The treatments for bowel endometriosis include shaving, nodulectomy, disc resection, and bowel resection. The surgeon should be capable of performing any of these procedures as needed at the time. In some cases this may be the main excision surgeon, if they have bowel surgery training and hospital prvileges, and in other cases, this may be another surgeon who is part of the backup team. In the latter situation, it is best if the possibility of bowel surgery and options are addressed before surgery and not as an emergency during surgery, when appropriate surgeons may not be readily available.

Lifestyle Changes

Alongside medical treatment, lifestyle changes can aid in managing bowel endometriosis symptoms. Some patients find that certain foods or lifestyle habits, such as stress or irregular sleep, may trigger their symptoms. Keeping a journal to track triggers and consulting with a healthcare provider or nutritionist when making dietary changes can be beneficial.

Read More: How to Treat Bowel Endometriosis: A Comprehensive Guide

Coping with Bowel Endometriosis

Living with bowel endometriosis can be challenging, but with the right diagnosis, treatment, and management, individuals can lead fulfilling lives. It’s essential to communicate openly with healthcare providers about symptoms and concerns, as this can aid in diagnosis and treatment planning.

In conclusion, bowel endometriosis is a painful and often misunderstood condition. Increased awareness and understanding of the disease can help in early diagnosis, effective treatment, and improved quality of life for those affected. If you suspect you might have bowel endometriosis or are experiencing any of the symptoms mentioned, do not hesitate to seek medical advice.

References:

Surgical Outcomes after Colorectal Surgery for Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Can Endometriosis Cause Bowel Issues?

Endometriosis is a common but often under-recognized condition, primarily affecting women between 15-50. It results from the growth of tissue similar to the endometrium (the lining of the uterus) outside the uterus. This article explores the question: Can endometriosis cause bowel issues?

Table of contents

- Understanding Endometriosis

- Endometriosis and Bowel Involvement

- Causes of Endometriosis

- Symptoms of Bowel Endometriosis

- Diagnosing Bowel Endometriosis

- Misdiagnosis of Bowel Endometriosis

- Treatment for Bowel Endometriosis

- Coping with Bowel Endometriosis

- The Importance of Early Detection

- Conclusion

- Additional Information

Understanding Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a condition where tissue, similar to the kind that lines the uterus (the endometrium), grows outside the uterus. This condition usually affects the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and the tissue lining the pelvis. However, in some cases, it can also affect other organs, including the bowel.

Endometriosis and Bowel Involvement

When endometriosis affects the bowels, it typically occurs in two forms:

- Superficial: The endometriosis tissue is located on the surface of the bowel.

- Deep: The endometriosis tissue passes through the bowel wall.

In both cases, doctors usually find a small mass of tissue, known as a lesion, on the bowel wall. More rarely, these lesions can penetrate into the muscular layer of the bowel.

Read More: Endometriosis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Distinguishing the Differences

Causes of Endometriosis

While the definitive cause of endometriosis remains unknown, several contributing factors have been identified. These include hormonal imbalances, immune system problems, and genetic factors.

Symptoms of Bowel Endometriosis

The symptoms of bowel endometriosis can vary, depending on the location and size of the lesion, and how deep it is within the bowel wall. These symptoms often mimic those of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but there are key differences.

Some of the common symptoms include:

- Trouble pooping or loose, watery stools (constipation or diarrhea)

- Pain during bowel movements

- Menstrual discomfort

- Painful sex

- Difficulty getting pregnant (infertility)

- Blocked bowel (this is a rare symptom)

Diagnosing Bowel Endometriosis

Diagnosing bowel endometriosis can be challenging due to its similarities with other conditions. However, if you have other endometriosis symptoms, such as painful periods, painful sex, lower back pain, or abdominal bloating and discomfort, it’s critical to talk to your doctor.

Read More: Understanding Bowel Endometriosis

Misdiagnosis of Bowel Endometriosis

Unfortunately, bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome or other gastrointestinal diseases. This is because the symptoms of bowel endometriosis can mirror those of IBS, Crohn’s disease, and appendicitis.

Read More: Finding an Excision Specialist: What you Need to Know

Treatment for Bowel Endometriosis

Treatment for bowel endometriosis is usually tailored to the patient’s symptoms and medical history. The most common treatments include surgery, hormone treatments, and counseling.

Coping with Bowel Endometriosis

Bowel endometriosis is a challenging condition to live with. It not only affects your physical health but also your mental well-being. Many patients have found some symptom relief through lifestyle changes, including dietary adjustments and regular exercise.

The Importance of Early Detection

Given the potential complications of bowel endometriosis, early detection and treatment are crucial. If you experience bowel issues alongside painful menstruation, it’s essential to consult with a healthcare professional.

Conclusion

The question, “Can endometriosis cause bowel issues?” is undoubtedly answered with a resounding yes. However, with timely detection, appropriate treatment, and necessary lifestyle changes, it’s possible to manage the symptoms and lead a healthy life.

Additional Information

This article is a comprehensive exploration of how endometriosis can impact bowel health. It’s essential to remember that while this condition can cause significant discomfort and health issues, effective treatments are available. If you suspect you have endometriosis, don’t hesitate to reach out to a healthcare provider.

References:

https://www.webmd.com/women/endometriosis/bowel-endometriosis

https://www.endofound.org/gastrointestinal-distress

https://maidenlanemedical.com/endometriosis/endometriosis-and-constipation/

https://drseckin.com/bowel-endometriosis/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4604671/

Endometriosis Affects Sexual Function: What You Need to Know

Many people know endometriosis as a “menstrual” disease or associate it with painful periods and/or infertility; however, endometriosis impacts many aspects of one’s life, including sexual function and intimacy.. This article aims to shed light on the complex interplay between endometriosis and sexual dysfunction, highlighting the critical points from recent scientific findings and providing an empathetic and informative perspective for those affected by the condition.

Table of contents

Impact on Sexuality

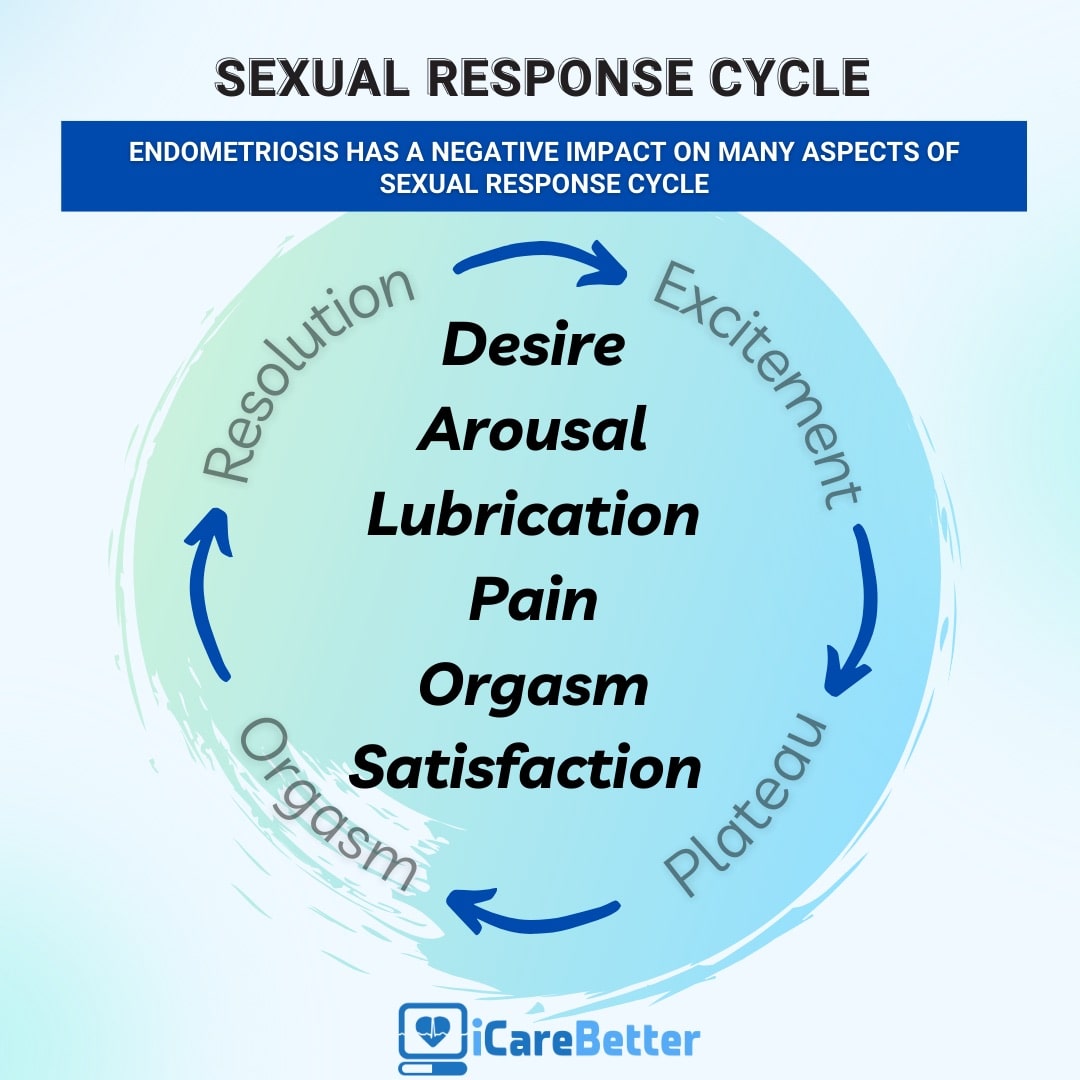

Endometriosis is notorious for causing severe pelvic pain, which is often exacerbated during menstruation. However, its effect extends beyond physical discomfort, with a significant impact on a woman’s sexual function. The correlation between endometriosis and sexual dysfunction is a compelling topic for scientific research, as it profoundly affects the quality of life of those living with this condition. One of the primary clinical manifestations of endometriosis is dyspareunia. What is important to know is that the lesions may directly cause deep dyspareunia (pain with deep thrusting), though the lesions as well as ‘treatments’ for endometriosis may also impact sexual functioning and leads to a decrease in sexual desire or arousal, resulting in a cycle of distress and avoidance of sexual intimacy.

Beyond Pain: Emotional and Psychological Effects

The effects of endometriosis on sexual function aren’t limited to physical symptoms. The condition can also trigger feelings of anxiety, distress, and guilt, affecting a woman’s self-esteem and overall mental health. Furthermore, the chronic nature of endometriosis and its association with infertility can impose additional psychological stress, further exacerbating sexual dysfunction. Over time, one may anticipate the pain, or have anxiety about what the sexual experience may be like, therefore causing reduced desire and arousal, or resulting in avoidance of sex or intimacy altogether.

Understanding the Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction in Endometriosis

A significant proportion of women living with endometriosis experience some form of sexual dysfunction. However, the severity and type of dysfunction can vary greatly, influenced by factors such as the type and extent of endometriosis, individual pain tolerance, and psychological well being.

Several scientific studies have delved into the intricate relationship between endometriosis and sexual dysfunction. A systematic review of nine studies conducted between 2000 and 2016 found that around two-thirds of women with endometriosis experienced some form of sexual dysfunction. These dysfunctions extended beyond deep dyspareunia, encompassing issues like hypoactive sexual desire, arousal problems, and orgasmic disorders.

The Role of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis (DIE)

Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis (DIE), a severe form of the disease, is often associated with a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction. Studies focusing on patients with DIE have found a significant impairment in various aspects of sexual functioning, including satisfaction, frequency of intercourse, and orgasm.

The Multidimensional Nature of Human Sexuality

Human sexuality is a complex phenomenon, influenced by a multitude of physical, psychological, and relational factors. As such, sexual dysfunction in women with endometriosis is not solely a result of physical pain but can also be shaped by the individual’s mental health and the quality of their intimate relationships.

Psychological distress, often associated with chronic pelvic pain, can significantly affect sexual functioning. Women living with endometriosis often experience anxiety and depression, which can act as powerful inhibitors of the sexual response cycle.

The quality of intimate relationships plays a crucial role in shaping sexual function. Marital satisfaction, perceived partner support, and the degree of intimacy can significantly influence the sexual experiences of women living with endometriosis.

Addressing Sexual Dysfunction in Endometriosis: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Given the multifaceted nature of sexual dysfunction in endometriosis, a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach is crucial for effective management. Such an approach extends beyond medical treatment for painful symptoms, encompassing psychological support and psychosexual therapy.

Your general gynecologist or endometriosis specialist may not necessarily be the person to also address your sexual dysfunction. This is a major area in which many providers are not trained in. ISSWSH, which stands for the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health, is an international, multidisciplinary organization that focuses on sexual health. Often, these people are the ones you want to see in regards to your sexual dysfunction. They include urologists, gynecologists, mental health professionals, physical therapists, nurse practitioners and more.

Psychological support is crucial in managing the mental health challenges associated with endometriosis. Therapists and psychologists can provide coping strategies for anxiety and depression, addressing feelings of guilt and distress associated with sexual dysfunction.

Empowerment Through Knowledge

Education and awareness are powerful tools in managing endometriosis and its impact on sexual function. By understanding the nature of the disease and its potential effects on their sexual health, women can seek appropriate help and take proactive steps towards improving their quality of life.

Endometriosis and its impact on sexual function is a complex issue, requiring a multifaceted, compassionate, and patient-centric approach. By acknowledging the physical, psychological, and relational aspects of sexual dysfunction, healthcare professionals can provide holistic support to those living with endometriosis, empowering them to navigate the challenges of this chronic condition and enhancing their overall quality of life.

Related reading:

- Endometriosis Pain after Orgasm: What You Need to Know

- Understanding the Relationship between Sex and Endometriosis

- What You Need to Know About Endometriosis and Intimacy

References:Barbara, G., Facchin, F., Buggio, L., Somigliana, E., Berlanda, N., Kustermann, A., & Vercellini, P. (2017). What Is Known and Unknown About the Association Between Endometriosis and Sexual Functioning: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Reprod Sci, 24(12), 1566-1576. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719117707054

Understanding Endometriosis: Unveiling the Common Symptoms and Their Impact

Table of contents

A recent article from Australia on common symptoms and endometriosis was released recently that followed several thousand women that were both surgically and clinically diagnosed (evaluated separately) with endometriosis and their symptoms to look at associations. There are minimal longitudinal studies available, so this article can be very impactful in raising awareness of the variable, but common, symptoms those with endometriosis experience.

Endometriosis, a chronic gynecologic disorder, is characterized by the presence of endometrium-like tissue outside the uterus. This condition has a profound impact on women’s (XX) lives, often leading to increased hospitalizations, diminished work productivity, and a reduced quality of life. While menstrual symptoms are the most commonly associated with endometriosis, an array of other symptoms can significantly affect the physical and mental wellbeing of women diagnosed with this condition. This article aims to provide an in-depth understanding of the common symptoms associated with endometriosis and their impact on women’s health.

The Prevalence of Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a prevalent health condition affecting approximately 1 in 9 women (11.4%) in Australia by the age of 44 years and in the US the estimation is 1 in 10, though this may be inaccurate due to the significant delay or issues with misdiagnosis. The nonspecific nature and normalization of the symptoms often lead to a significant delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis, with several studies reporting an average delay of 7 to 11 years. This delay in diagnosis results in untreated endometriosis-related symptoms, increased hospitalizations, higher healthcare resource utilization, and potentially reduced success using assisted reproductive technologies. Additionally, some of the overlapping symptoms may be due to the “treatments” offered for symptom management such as hormonal supressive therapies.

Endometriosis and Menstrual Symptoms

Women diagnosed with endometriosis frequently report an array of menstrual symptoms. These may include severe period pain (dysmenorrhea), heavy menstrual bleeding, irregular periods, and premenstrual tension. The association between endometriosis and these symptoms is strong, with the odds ratio for severe period pain being as high as 3.61.

Endometriosis and Mental Health Problems

Apart from physical discomfort, endometriosis can significantly affect a woman’s mental health. Studies reveal a higher incidence of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders, in women with endometriosis. The adjusted odds ratios for depression and anxiety are 1.67 and 1.59, respectively.

Endometriosis and Bowel Symptoms

Bowel symptoms are another common complaint among women with endometriosis. These may include constipation, hemorrhoids or piles, indigestion, or heartburn, bloating, diarrhea, or a combination of these. Additionally, one of the clinical manifestations is dyschezia, or discomfort/pain associated with bowel movements. The adjusted odds ratio for constipation is 1.67, indicating a significant association between endometriosis and bowel symptoms. Additional studies have demonstrated that approximately 90% of those with endometriosis have IBS-like symptoms.

Endometriosis and Urinary Symptoms

Urinary symptoms, such as burning with urination (dysuria) and vaginal discharge or irritation, are also more prevalent in women with endometriosis. The increased odds of urinary symptoms suggest a possible alteration in the pelvic innervation caused by endometriotic lesions.

Endometriosis and Pain Symptoms

Endometriosis is often associated with other forms of pain, including back pain, headaches or migraines, and stiff or painful joints. The adjusted odds ratios for these pain symptoms range from 1.50 to 1.76, further emphasizing the multifaceted impact of endometriosis on women’s health.

Endometriosis and Nonspecific Symptoms

In addition to the symptoms described above, endometriosis is also linked to various nonspecific symptoms. These may include severe tiredness, difficulty sleeping, palpitations, and allergies or hay fever or sinusitis. The association between endometriosis and these symptoms underlines the complex nature of this condition and its wide-ranging effects on women’s health.We need more understanding whether these symptoms are a direct result of the endometriosis, the side effects of treatments, or another related issue.

The Importance of Early Diagnosis

Given the wide array of symptoms associated with endometriosis and their significant impact on a woman’s quality of life, the importance of early diagnosis and treatment cannot be overstated. Early intervention can not only alleviate the physical discomfort associated with the disease but also significantly improve mental health outcomes. Furthermore, it can potentially prevent the development of chronic pain conditions and other long-term health complications.

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a complex condition that affects multiple aspects of a woman’s health. It is associated with a wide range of symptoms, extending beyond menstrual problems to include mental health issues, bowel and urinary symptoms, pain, and other nonspecific symptoms. Understanding these symptoms and their impact on women’s lives is crucial for providing comprehensive care to those diagnosed with this condition. While further research is needed to elucidate the specific mechanisms underlying these associations, the current evidence underscores the importance of early diagnosis and intervention in improving health outcomes for women with endometriosis.

Related reading:

- Understanding fatigue and endometriosis: A Practical No-Nonsense Guide

- Interstitial Cystitis and Endometriosis: Unraveling the “Evil Twins” Syndrome of Chronic Pelvic Pain

- Endometriosis Signs and Symptoms: Everything You Need to Know

References:

- Gete DG, Doust J, Mortlock S, et al. Associations between endometriosis and common symptoms: findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023;229:536.e1-20.

Understanding the Relationship between Sex and Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a painful condition that affects millions of women around the world. It occurs when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside of the uterus, causing inflammation, pain, and other symptoms. The pain can be so severe that it can affect women’s daily activities, including their sex lives. For many women, sex and endometriosis do not mix well. In fact, many women report that sex exacerbates their symptoms. In this blog post, we will explore the relationship between sex and endometriosis, explore some sex tips for managing endometriosis, and discuss the psychological and emotional effects of the condition.

How Endometriosis Can Affect Sex Life

Endometriosis tissue can attach to the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or other pelvic organs and can cause pain, swelling, and sometimes infertility. It can cause pain during or after sex, painful periods, and chronic pain. This can make it challenging for women to enjoy their sexual partners or have comfortable sex. During sexual activity, endometriosis can cause pain, especially during deep penetration or certain positions. It can also cause pain during orgasms.

Read more: Endometriosis Pain after Orgasm: What You Need to Know

Pain during sex can be due to adhesions, scar tissue, or inflammation in the pelvic area. Endometriosis tissue can also grow in the vagina or cervix, making intercourse painful. In addition, vaginal dryness can exacerbate the problem, and many women taking hormone medicines for endometriosis may experience a decrease in libido, which can further affect their sex drives.

Ways to Manage Pain from Endometriosis

If you are struggling with painful sex due to endometriosis, there are things you can do to manage your symptoms. Firstly, you should communicate with your partner about your symptoms and pain levels. This can help your partner know how to support you and modify sex positions to ease the pain. Additionally, you can try different positions to find the ones more comfortable for you. Lubricants and non-penetrating sexual acts might also be some strategies to think about.

Endometriosis can also affect women’s emotional and psychological health, leading to depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues. This can further affect women’s sex lives by reducing their interest in sex, increasing their fear or anxiety during sex, and making it difficult to enjoy intimacy. It is important to seek professional help if you are experiencing any mental health issues related to endometriosis. Counseling, therapy, or medication can help you manage your emotional and psychological symptoms, leading to a healthier sex life.

In addition to planning sexual activity, you can also manage pain from endometriosis by using pain-relieving medications or hormone therapy. Your doctor may also recommend surgery to remove endometriosis tissue or other affected organs.

Sex and endometriosis may not always mix well, and many women may find it difficult to enjoy intimacy due to pain and other symptoms. However, with the right communication, management strategies, and emotional support, women with endometriosis can still have a satisfying sex life. It is important to communicate with your partner, try different positions, and seek professional help if the condition affects your emotional and psychological health. Remember, endometriosis does not define your worth or your ability to enjoy intimacy. With the right support, you can still have meaningful, fulfilling relationships and happy sex lives.

Read more:

5 Signs You Need to See a Gynecologist

Find an Endometriosis Specialist for Diagnosis, Treatment, & Surgery

Spotting the Signs of Endometriosis Returning

Endometriosis is a painful and challenging condition. While there is no cure for this condition, treatments are available to manage the symptoms, making it easier for patients to lead healthy lives. However, endometriosis can recur, and it is crucial to identify the signs and symptoms to avoid complications. In this post, we will discuss the symptoms of endometriosis recurrence and how to spot them early enough so you can seek medical attention.

Table of contents

Painful Periods

One of the signs of endometriosis returning is pain during your period. This pain can range from minor discomfort to excruciating cramps that require you to take painkillers. If you notice that your periods are more painful than usual or that the pain increases over time, it may be a sign that your endometriosis is returning. Keep a record of your symptoms, including any changes in frequency, intensity, and duration of your period, so you can discuss them with your doctor.

Pelvic Pain

Another sign of endometriosis recurrence is persistent pelvic pain or discomfort. This pain can be mild, moderate, or severe and may come and go, depending on hormonal fluctuations. Some patients may also experience pain during sex or ovulation. If you notice persistent pelvic pain, scheduling an appointment with your doctor to discuss your treatment options is essential.

Fatigue

Endometriosis can cause fatigue due to the pain and stress that comes with the condition. If you notice that you are more exhausted than usual, despite enough rest, it could be a sign that your endometriosis is returning. Speak with your doctor and seek support from a therapist or counselor to manage the mental impact of endometriosis.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Endometriosis can affect the digestive system, causing symptoms such as bloating, constipation, or diarrhea. These symptoms may worsen during or after your period, and they may not improve with changes to your diet or bowel habits. If you notice gastrointestinal symptoms, mentioning them to your doctor is essential, as they may be a sign of endometriosis recurrence.

Other Symptoms for Endometriosis Recurrence

Endometriosis presents itself in many ways. We mentioned some of it here, but there are undoubtedly many other symptoms that can help diagnose the recurrence of endometriosis. You should keep track of your well-being and mention any unusual symptoms or abnormalities to your doctor.

Endometriosis can cause severe pain and discomfort and impact your quality of life. While timely diagnosis and treatment can help manage the symptoms and prevent complications, there are risks of recurrence after surgery. The signs of recurrence are pelvic pain, period pain, fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, and other symptoms. If you notice any signs of endometriosis returning, speak with your doctor.

Please share the signs of endometriosis returning that you had experienced.

5 Signs You Need to See a Gynecologist

Table of contents

Regular gynecologist visits are essential to maintaining sexual and reproductive health. However, many women put off making an appointment until they are pregnant or facing a problem. There are several reasons to visit a gynecologist. If you’re unsure whether you need to see a gynecologist, here are five signs that it’s time to schedule an appointment.

You Haven’t Been in a While (Or Ever)

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that women have their first gynecological visit when they turn 18 or become sexually active, whichever comes first. If you’re overdue for a checkup, it’s time to schedule an appointment. Remember that you don’t need to be sexually active to see a gynecologist – they can provide comprehensive care for all aspects of your reproductive health, even if you’re not sexually active.

You’re Experiencing Abnormal Bleeding

If you’re bleeding between periods, after sex, or after menopause, it’s time to see a gynecologist. Abnormal bleeding can be caused by everything from uterine fibroids to endometriosis to cervical cancer, so getting checked out as soon as possible is important.

You Have Painful Periods

Periods are supposed to be discomforting, but they shouldn’t be so painful that they interfere with your daily life. If you miss work or school because of period pain, it’s time to see a gynecologist. They may be able to diagnose the underlying reason for your pain and help with the treatment.

You Have Pelvic Pain Outside of Your Periods

If you’re experiencing pelvic pain at any time other than during your period, it could be a sign of endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or another condition. Many conditions that cause pelvic pain can be treated if they’re caught early, so don’t hesitate to make an appointment with your gynecologist.

You Have New and Unusual Symptoms

If you’ve started experiencing new and unusual symptoms – like changes in your vaginal discharge or burning during urination – it’s time to go to the gynecologist. These could be signs of infection or another problem, so getting checked out as soon as possible is best.

If you’re experiencing any of the above symptoms, don’t wait – schedule an appointment with your gynecologist today! The sooner you get checked out, the sooner you can start feeling better and return to your normal routine. In addition to the five signs we reviewed here, there are countless other reasons to visit a gynecologist. So it would be best to stay informed about your health and communicate with your doctors about any questions or concerns.

What Would Happen to the Signs and Symptoms of Endometriosis After Menopause?

Table of contents

- Managing Endometriosis During Menopause

- Reducing the Severity of Endometriosis Symptoms During Menopause

- Taking Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT)

- Taking Pain Relievers Like Ibuprofen or Acetaminophen

- Reducing Stress with Relaxation Techniques like Yoga or Meditation

- Exercising Regularly

- Pelvic Floor Therapy

- Don’t Suffer with Prolonged Severe Symptoms

Endometriosis during menopause was first recognized over fifty years ago. But, because it is reported in only about 2-5% of women with endo, it is simply not discussed much. The actual percentage may be higher, but the talking points still focus on endometriosis somehow going away after menopause. This is simply not true in all endo patients; in some cases, endo can even start after menopause.

Unfortunately, there is still much unknown about endometriosis after menopause. Some studies have shown that the severity of symptoms may lessen with age. In contrast, others have found that endometriosis can worsen after menopause, especially when you consider adenomyosis of the uterus which can persist for decades into menopausal years. So, managing the symptoms for many women suffering from this condition becomes a lifelong battle. Suppose you are experiencing pelvic pain or intestinal symptoms that may be related to endometriosis near or after menopause. In that case, it’s important to talk to your doctor about your options for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Managing Endometriosis During Menopause

Whether it be endometriosis resolving or the effects of prior surgery, scarring is one of the normal processes your body uses to heal. Either persistent active endo or adenomyosis or the scars or fibrosis on various organs and the peritoneum can cause persistent symptoms. Assuming you do not take estrogen replacement with a known history of endometriosis, estrogen in your body still exists in varying amounts because your fat cells convert other hormones or toxins into estrogen. On top of that, the amount of estrogen required to make endo grow varies between individuals, and estrogen is not the only molecular driver to make endo grow. For all these reasons, pain from endo persists into menopause in at least 2-5% of patients. The treatment overlaps regardless of why the symptoms may be present but is not exactly the same.

Reducing the Severity of Endometriosis Symptoms During Menopause

What about surgery? Since accurate blood test biomarkers are still not available, surgery can’t be ignored as a possible part of the plan. Regardless of whether it is persistent endo or newly developing endo, scars from endo healing or progressive scarring from prior excisions, expert evaluation for possible surgical intervention should be a cornerstone in planning. Based on a risk vs. benefit discussion with an expert surgeon, a consult with an expert is the best way to determine what is going on after menopause. This consult can help form the best treatment plan beyond the excision of endometriosis, scar, or even possible hysterectomy. If, for example, persistent adenomyosis is the cause of your pain, then surgery may be hands down the best option to eliminate the pain.

If active endo is responsible for the symptoms, it is possible to reduce symptom severity through some general adjustments. This adjustment includes diet and lifestyle modifications. Reducing stress levels by finding calming activities like yoga or meditation, eating an anti-inflammatory diet high in fiber (to absorb excess estrogen in the gut), and engaging in regular physical activity can all help ease endometriosis pain in some. These are general recommendations and depend on what else, like SIBO or irritable bowel syndromes, may be going on.

Combining mainstream medication options with integrative support could significantly reduce the discomfort of endometriosis symptoms post-menopause, allowing many women a chance to reclaim their quality of life. The following are some specific considerations.

Taking Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT)

Taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is an important treatment decision. HRT is a form of medication that uses hormones to relieve menopausal symptoms. If the uterus is still present, then both estrogen and progesterone are required in order to reduce the risk of uterine cancer. If not, then estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) alone may be better because this means a lower risk of developing breast cancer. However, it is controversial whether HRT or ERT can make endo grow. Scientific data suggests that HRT may be better in this regard, but this is not clear-cut. Similarly, it is unclear if herbal or plant-based estrogen replacement is safe, and, based on complex molecular biology factors, it is probably different in each individual. Always keep in mind that your body is never in a zero-estrogen state because your fat cells convert other hormones into estrogen, and toxins you are constantly exposed to (xenoestrogens) can also factor in.

Taking Pain Relievers Like Ibuprofen or Acetaminophen

Taking pain relievers like ibuprofen or acetaminophen might be an effective way to manage intermittent mild to moderate endometriosis pain. Of course, there are side effects that are usually mild, which must be balanced when compared to the benefit of longer-term use. A pain specialist may recommend using stronger medications such as narcotics, gabapentin, or related drugs. Generally, it is not recommended to take any of these medications continuously. More importantly, relying on pain medications alone is like putting a band-aid on a gaping wound without repairing the wound. A better strategy is to deal with the root cause and try to correct it. Determining if the root cause for pain is endo or adenomyosis related in menopause requires a consult with an endometriosis specialist and, ideally, one who specializes in peri and postmenopausal endo.

Reducing Stress with Relaxation Techniques like Yoga or Meditation

Yoga and meditation have been demonstrated to effectively mitigate stress levels, which may reduce endometriosis-related symptoms. How this happens is poorly understood, but it may be mediated by cortisol level alterations or epigenetic regulation of pain receptor-related gene expression. This is a very subjective area and hard to study objectively, but research is ongoing. One can’t go wrong with this option because it does not carry risk and can benefit your health in multiple ways.

Exercising Regularly

Regular exercise is a meaningful way to maintain physical and mental health, whatever your age or circumstances. For endometriosis patients, in particular, being physically active can help reduce inflammation and adapt the body’s response to pain. Studies have also shown that regular workouts may help endometriosis sufferers manage endocrine problems, anxiety, and stress levels. With physical exercise, endometriosis patients benefit from improved quality of sleep too. So this is another low-risk lifestyle modification that can reap many benefits.

Pelvic Floor Therapy

The inflammation from endometriosis and/or direct nerve impingement at the pelvic floor can cause pain in menopause, just like during the reproductive years. The muscles and fascia over-react and spasm, which can be relieved with pelvic floor physical therapy. In some cases, it can help with fibrosis or scar-related pain by restoring normal motion. Usually, this requires a program and is not a one-time deal, so a consultation with a pelvic floor therapist is definitely worth considering. Pelvic floor therapy may or may not be the solution for you. If pain persists, surgical options may still need to be considered to get to the root of the problem.

Don’t Suffer with Prolonged Severe Symptoms

After menopause, many women find that their endometriosis and other symptoms still impact their life significantly, even if they follow prudent diet and lifestyle modifications. If you are in this situation, don’t hesitate to speak to an endometriosis expert about the potential benefits and risks of surgery and other treatment options available. Molecular markers for endo may be coming soon, but today surgery is the only way to accurately diagnose endo. Especially when pain persists into menopause or starts in menopause, other conditions may be the cause or overlapping endometriosis and adenomyosis. Surgical treatment may or may not be the right answer for you, but expert guidance and complete evaluation is better than waiting the pain out and hoping it will go away.