TENS Therapy: A Non-invasive Pain Relief Option for Dysmenorrhea

Table of contents

Dysmenorrhea and endometriosis are two common health issues that many women face. These conditions often cause severe pelvic pain, disrupting everyday life. Pain relief for these conditions traditionally involves medication whether it be oral contraceptive pills or other hormonal suppressive medications or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, which can sometimes lead to unwanted side effects. In many cases, those with endometriosis need additional support as these are not always effective. While excision surgery should be discussed, even those who have had successful surgeries continue to have persistent pain. Conditions such as dysmenorrhea, adenomyosis, and endometriosis can all contribute to persistent pain. Our blog titled Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Decoding Their Contribution To Pelvic Pain helps explain these connections.

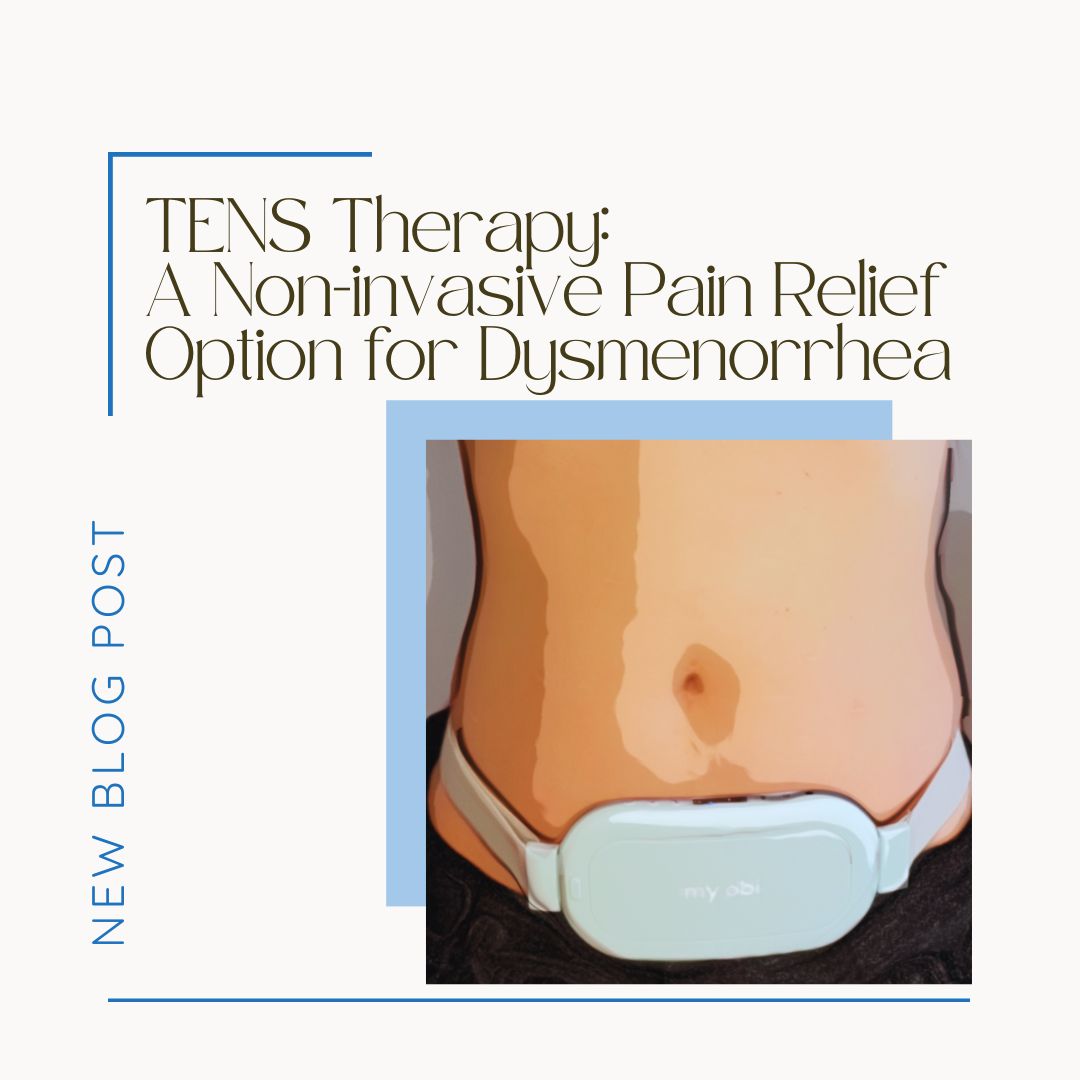

Modalities do exist that can be helpful for some, with a low side-effect profile. One particular modality of interest has been various Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) devices, and there have been improvements in these devices especially for those with dysmenorrhea also known as painful periods. One device that we are fond of is the Apollo from My Obi.

What is TENS Therapy?

TENS therapy is a pain management technique that uses low-voltage electrical currents to alleviate pain. It’s a non-invasive treatment that doesn’t involve medication, making it an attractive option for those who experience side effects from traditional pain relief methods.

How Does TENS Therapy Work?

TENS therapy functions by sending electrical currents through the skin to stimulate the nerves. These currents trigger the production of endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers, and block the pain signals from reaching the brain. The intensity and duration of the current can be adjusted to suit individual needs and pain tolerance.

Operation of TENS Devices

TENS devices, such as the Apollo belt and the OVA device, are designed to be user-friendly. They are lightweight and can be clipped onto clothing, allowing users to continue with their daily activities while receiving treatment. The devices come with preset programmes, which the user can select and adjust according to their comfort level.

Benefits of TENS Therapy

TENS therapy offers numerous benefits, especially for women suffering from dysmenorrhea and endometriosis. They are often readily available and affordable, some devices offer a heating option as well!

Non-pharmacological Treatment Option

One of the main advantages of TENS therapy is that it’s a non-pharmacological treatment. It doesn’t involve medication, reducing the risk of side effects or interactions with other drugs.

Increased Blood Flow

TENS therapy can also increase blood flow to the abdomen. This improved circulation helps to reduce inflammation and swelling, further relieving pelvic pain.

User-Controlled

TENS therapy is controlled by the user. This means the intensity and duration of treatment can be adjusted to suit individual needs and pain levels.

Effectiveness of TENS Therapy for Period Pain and Endometriosis

Several studies support the use of TENS therapy for period pain and endometriosis. A review of these studies found TENS therapy to be effective in reducing pain in women with primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. In terms of endometriosis, TENS therapy may offer a viable treatment option, although more research is needed in this area.

Side Effects and Contraindications

TENS therapy is generally safe with few side effects. However, it may not be suitable for everyone. For instance, people with heart conditions or those with a pacemaker should avoid TENS therapy. It’s always best to consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new treatment.

Summary

TENS therapy provides a non-invasive, user-controlled, and effective pain relief solution for dysmenorrhea and endometriosis. It increases blood flow and stimulates the production of endorphins. Moreover, it’s a non-pharmacological treatment, making it an attractive option for those who experience side effects from traditional pain relief methods. However, it’s always best to consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new treatment.

The potential of TENS therapy is promising, and further research could unlock more benefits for women suffering from pelvic pain. By exploring alternative treatments like TENS therapy, we can continue to improve the quality of life for those affected by conditions like dysmenorrhea and endometriosis. If you suffer from pelvic pain or dysmenorrhea you may want to seek help from a specialist, not sure? Read about the signs and symptoms that warrant help here!

References:

Schiotz, H. A., Jettestad, M., & Al-Heeti, D. (2007). Treatment of dysmenorrhoea with a new TENS device (OVA). J Obstet Gynaecol, 27(7), 726-728.

History of Endometriosis: Unraveling the Theories and Advances

Table of contents

Endometriosis is a complex condition that affects a significant number of women (XX) and on average takes 7-10 years for a diagnosis. The majority of people date their symptoms back to adolescence though go years seeking answers. Throughout their journey, many people receive either a wrong diagnosis or were simply dismissed altogether. In recent years, there has been a marked improvement in the recognition of the word ‘endometriosis’ but why does this disease remain such an enigma to so many healthcare professionals? Furthermore, endometriosis has been a subject of medical investigation for over a century with debates about how to approach treatment, understanding of the pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and treatment methods.

Research in this field has evolved over time, but are we really that much further along than we were a century ago? One of the most frustrating concepts for those of us who truly understand endo, is the regurgitation of the theory of retrograde menstruation postulated in the 1920’s by Dr. John A. Sampson. The theory that endometriosis is derived from retrograde menstruation is an incomplete understanding of this original theory, that has perpetuated misinformation and our current recommended treatments – hormonal suppression and hysterectomies. Sampon’s original theory was more involved, but future research into alternative theories seems much more promising. Even so, our current “validated or trusted treatments” are still rooted in early understanding. This article delves into the intricate history of endometriosis, tracing its theories and advances, or lack thereof, to provide a comprehensive overview of this complex condition.

The Early Recognition of Endometriosis

Initial Observations and Descriptions

The first description of a disease resembling endometriosis can be attributed to Thomas Cullen in the early 20th century.1 Cullen identified endometriosis and adenomyosis as a single disease, characterized by the presence of endometrium-like tissue outside the uterine cavity.2 This breakthrough laid the foundation for future research and understanding of endometriosis.

Sampson’s Theory of Retrograde Menstruation

The term “endometriosis” was coined by John A. Sampson in the late 1920s.3 Sampson proposed the theory of retrograde menstruation as the primary cause of endometriosis, due to the observation during surgery of the similarity in endometriosis lesions and the endometrium, suggesting that endometrial cells are transported to ectopic locations via menstrual flow. This theory gained widespread acceptance and significantly influenced the direction of endometriosis research. Though he did note early on that there were additional factors to allow the growth of these lesions to transform, similar to more current theories and the immune system involvement.

Advances in Diagnosing Endometriosis

The Advent of Laparoscopy

The introduction of laparoscopy in the 1960s revolutionized the diagnosis of endometriosis.4 This minimally invasive surgical procedure allowed physicians to visually identify and classify endometriosis lesions, leading to a significant increase in the diagnosis of the disease.

Differentiating Clinical Presentations

With the advent of laparoscopy, three distinct clinical presentations of endometriosis were identified: peritoneal, deep adenomyotic, and cystic ovarian.5 These classifications, along with advances in imaging techniques such as ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have improved the precision of endometriosis diagnosis.

Development of Medical Therapies for Endometriosis

Early Interventions

The first attempts at treating endometriosis with synthetic steroids began in the 1940s.6 Initially, androgenic substances were used, but their side effects led to a search for more effective and tolerable treatments. Fun fact: testosterone was actually the first hormone used in attempts to “treat” the disease.

The Pseudo-pregnancy Regimen

The 1950s saw the advent of the “pseudo-pregnancy” regimen, where hormones were used to mimic the hormonal environment of pregnancy, thereby suppressing ovulation and endometrial growth.7 During this time, there were limited options and this suggestions came from the observation that symptoms were improved when pregnancy occurred. This approach utilized a combination of estrogen and progestin medications and marked a significant advance in the medical management of endometriosis. At this time, birth control was becoming more widespread and more options were being developed. The myth that is still perpetuated today by uninformed practitioners and society of “just get pregnant, it will cure your endo” or “just have a baby” stems from this belief. In 1953 a physician legitimized the limited options and made recommendations suggesting that frequent and often pregnancy was one of the only options and “subsidize your children” was the solution for the increased financial burden. There are so many infuriating suggestions at this recommendation, but the 50’s were a different time, with limited research and options.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Agonists

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists emerged as a primary medical therapy for endometriosis in the late 20th century.8 These drugs work by reducing the production of estrogen, thereby limiting the growth of endometriotic tissue, at least in theory. However, the side effects of hypoestrogenism led to the development of ‘add-back’ therapies to mitigate these effects.Not to mention poor regulation and research practices present in the 1990’s including falsified data on the true impact of these drugs.

Evolution of Surgical Treatments

Conservative Surgery & Advancements in Endoscopic Surgery

The development of laparoscopy also transformed the surgical management of endometriosis. Conservative surgical techniques, including the excision of visible endometriosis lesions and adhesion lysis, became feasible.9 These procedures aimed to preserve fertility while effectively managing the disease. The late 20th century saw further advancements (again, in theory) in laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Techniques such as CO2 laser vaporization and the use of circular staplers for bowel resection improved the effectiveness and safety of surgery.10

Unraveling the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis

The Role of the Peritoneal Environment

Research in the 1980s began to focus on the peritoneal environment’s role in endometriosis. Studies found evidence of a local peritoneal inflammatory process, including increased activation of peritoneal macrophages and elevated cytokine and growth factor concentrations.11

Endometrial Dysfunctions

Investigations also revealed biochemical differences between eutopic and ectopic endometrium in women with endometriosis. These differences suggested that endometriosis might be associated with endometrial dysfunction, contributing to both the pathogenesis and sequelae of the disorder.12 While research exists that shows differences in BOTH the endometriosis lesions and the endometrial environment, this is correlational research, and does not imply causation.

Immunological Factors

The involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of endometriosis was another significant discovery. Altered immune responses, including decreased T-cell and natural killer cell cytotoxicities, were observed in those with endometriosis.13

The Connection Between Endometriosis and Adenomyosis

In the late 20th century, researchers revisited the connection between endometriosis and adenomyosis, suggesting that the two conditions might represent different phenotypes of the same disorder.14 This theory proposed that both endometriosis and adenomyosis are primarily diseases of the junctional zone myometrium.

Modern Approaches to Endometriosis Treatment

Use of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist and Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System

In more recent years, GnRHa therapy, often combined with ‘add-back’ therapy, has become a popular “treatment” for endometriosis.15 The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), which releases a progestin hormone into the uterus, has also shown promise in the management of endometriosis-associated chronic pelvic pain.16 In reality, this may be more true for adenomyosis and further research is needed. Research with less bias seems to oppose these claims stating that “GnRH drugs show marginal improvement over no active treatment” when compared with other hormonal suppression medications. Thanks to marketing, this is not well known among consumers. 19 Not to mention the significant side effects that further contribute to the various chronic overlapping pain syndromes associated with endometriosis.

The Future of Endometriosis Research and Treatment

The evolution of endometriosis theories and advances underscores the complexity of this condition. As we continue to unravel the mysteries of endometriosis, there is an ongoing need for research into its pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. The future of endometriosis research and treatment lies in a deeper exploration of its genetic-epigenetic aspects, the role of oxidative stress, and the impact of the peritoneal and upper genital tract microbiomes.18

Conclusion

The history of endometriosis is marked by a continual evolution of theories, advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, and an expanding understanding of the disease’s complex pathogenesis. From the initial descriptions by Thomas Cullen to the modern laparoscopic techniques and hormonal therapies, the journey of understanding and treating endometriosis has indeed been a frustrating one.

One of the most frustrating aspects is that when we really understand the first observations of endometriosis in the 1800’s into the early 1900’s, it is not far from where we are today. This demonstrates the serious need for more research, better research, and more in depth understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment approaches for endometriosis. While this has improved in the last five years, it is not enough. We need to do more, and we need to do better. Healthcare policy change is an extremely slow process and in my personal observation, decided among individuals who show less understanding than those with the disease.

10. References

Disclaimer: This article is intended to provide general information on the topic and should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult with your healthcare provider for personal medical advice.

- Cullen, T. (1920). Adenomyoma of the Uterus. WB Saunders.

- Sampson, J.A. (1927). Metastatic or Embolic Endometriosis, due to the Menstrual Dissemination of Endometrial Tissue into the Venous Circulation. American Journal of Pathology, 3(2), 93–110.

- Sampson, J.A. (1927). Peritoneal endometriosis due to menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 14, 422–469.

- Brosens, I., & Benagiano, G. (2011). Endometriosis, a modern syndrome. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 133(6), 581–593.

- Amro, B., et al. (2022). New Understanding of Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Endometriosis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6725.

- Miller, E.J. (1944). The use of testosterone propionate in the treatment of endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 48(2), 181–184.

- Kistner, R.W. (1958). The use of newer progestins in the treatment of endometriosis. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 75(2), 264–278.

- Hughes, E., et al. (2007). Ovulation suppression for endometriosis for women with subfertility. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), CD000155.

- Brosens, I., et al. (2022). New Understanding of Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Endometriosis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6725.

- Keckstein, J., & Becker, C.M. (2020). Endometriosis and adenomyosis: Clinical implications and challenges. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 69, 92–104.

- Dmowski, W.P., & Braun, D.P. (1997). Immunology of endometriosis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 11(3), 365–378.

- Lebovic, D.I., et al. (2001). Eutopic endometrium in women with endometriosis: ground zero for the study of implantation defects. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 19(2), 105–112.

- Dmowski, W.P., & Braun, D.P. (1997). Immunology of endometriosis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 11(3), 365–378.

- Leyendecker, G., et al. (2009). Endometriosis results from the dislocation of basal endometrium. Human Reproduction, 24(9), 2130–2137.

- Surrey, E.S., & Soliman, A.M. (2019). Endometriosis and fertility: A review of the evidence and an approach to management. Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons, 23(2), e2018.00087.

- Vercellini, P., et al. (2003). Endometriosis and pelvic pain: relation to disease stage and localization. Fertility and Sterility, 79(2), 156–160.

- Sutton, C.J., et al. (1994). Laser laparoscopy in the treatment of endometriosis: a 5 year study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 101(3), 216–220.

- Brosens, I., & Benagiano, G. (2011). Endometriosis, a modern syndrome. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 133(6), 581–593.

- Johnson, N. P., Hummelshoj, L., & World Endometriosis Society Montpellier, C. (2013). Consensus on current management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod, 28(6), 1552-1568.

Navigating the Path to Your Best Endometriosis Specialist

The journey towards resolving endometriosis involves an important decision – selecting the best endometriosis specialist.

Table of contents

Determining Your Needs in a Surgeon

Being aware of your specific requirements can help you make an informed choice. Here are a few considerations you should keep in mind:

Training and Experience

A surgeon’s training, notably in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (MIGS) or Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (FMIGS) is crucial. Such surgeons have spent more time in operation theaters, honing their skills through extensive practice.

Ensure your surgeon is board-certified and inquire about their experience, including the number of surgeries they’ve performed, complications they’ve encountered, and outcomes.

Surgical Support Team

The surgeon’s team is equally important. Ask about their procedure in case of bowel, bladder, ureter, or diaphragmatic involvement. Inquire if everything can be done during a single procedure.

Approach to Excision

Surgeons may have different opinions on excision versus ablation. Find out their thoughts on the subject and where and when they excise or ablate.

Post-Surgery Care

Ask if the surgeon routinely prescribes suppressive medications pre and post-surgery. Understand their reasons if they do.

Costs

Don’t hesitate to inquire about costs, insurance acceptance, payment policies, and any hidden charges.

Comfort Level

Ensure you feel comfortable conversing with your surgeon and that your queries are answered satisfactorily.

Factors That May Not Influence Your Decision

Certain aspects may not influence the quality of surgical care:

- Gender: The surgeon’s gender does not impact their surgical ability.

- Preferred Tools: The surgical tool used is less important than the surgeon’s skill.

- Bowel Prep: Surgeons may have different preferences for bowel prep before surgery, but it doesn’t seem to influence the outcome.

Factors That Might Influence Your Decision

Some factors might play a role in your decision-making process:

- Reputation: Be cautious while considering a surgeon’s reputation. Some may get media coverage or have excellent bedside manners, but that doesn’t necessarily make them a skilled surgeon.

- Office Management: A well-managed front office can make your experience smoother.

- Location: Depending on your comfort and ability to travel, location might influence your decision.

- Timing: The availability of the surgeon and your urgency might also play a role.

The Most Important Factor

Patients often report being most satisfied with surgeons who actively listen to them. Your surgeon should respect your knowledge and experiences without objection to being recorded or having someone with you during consultations.

Leading Endometriosis Specialists

iCareBetter has a list of endometriosis specialists and surgeons vetted for their surgical skills.

Managing Your Relationship with Your Current Doctor

Dealing with a current doctor who might not be capable of handling your endometriosis can be challenging. Here are some tips:

- Think long-term, maintain a cordial relationship, and educate your doctor about your condition without alienating them.

- Be respectful and considerate of your doctor’s opinions.

- Try to keep your doctor on your side by asking for their support.

- Remain calm and collected during discussions.

- If you choose to seek surgery elsewhere and decide not to return to your current physician, send a copy of the operative and pathology reports with a note of gratitude.

- If your doctor dismisses you as a patient, consider it as a sign that it wasn’t a good fit.

- Routine care can be handled by a GP or Family Doctor, a Nurse Practitioner, or a Physician’s Assistant.

Acupuncture: An Underexplored Solution for Endometriosis Pain

Endometriosis is a complex, multifaceted health condition that predominantly affects women of reproductive age. Characterized by the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, this condition can lead to chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and infertility, significantly impacting the quality of life. Today’s treatment is limited to expert surgical excision and hormonal manipulation, with variable success. In recent years, acupuncture has gained attention as a potential complementary treatment for endometriosis-related pain. This ancient Chinese technique may hold promise for providing effective pain relief and enhancing overall well-being.

Table of contents

Understanding Endometriosis

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent, inflammatory gynecological disorder that can lead to chronic visceral pelvic pain and infertility. This condition is believed to affect approximately 10% to 15% of women during their reproductive years, causing symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, dyschezia, dysuria, and more. It is theorized that endometriosis-related changes might be a result of alterations in the peripheral and central nervous systems, predisposing affected individuals to other long-lasting pain conditions.

Despite the availability of hormonal, pharmacological and surgical treatments, many of these interventions fail to sufficiently address the perceived pain. Moreover, they often come with significant side effects, presenting an additional burden of symptoms and potential for harm.

Read more: 20 Signs and Symptoms of Endometriosis.

Read more: What causes endometriosis?

The Science of Acupuncture:

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese medicine technique that involves inserting thin needles into specific points on the body to balance the flow of energy or “Qi”. It has been used for centuries to treat various conditions, including pain and inflammation. The modern science corollary is that acupuncture may work by stimulating nerves, muscles, and connective tissues, which increases blood flow and activates the body’s natural painkillers. While this modern evidence supports the use of acupuncture it is important to keep in mind that energy medicine is quite poorly understood. Acupuncture is an ancient form of energy medicine. A lot more research is mandated to understand how this truly works and how it might be improved or adjusted on an individual basis.

Acupuncture and Endometriosis:

Pain Relief

For endometriosis sufferers, the most significant benefit of acupuncture is pain relief. A study by Wayne et al. (2008) revealed that acupuncture significantly reduces pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and discomfort associated with endometriosis, enhancing the quality of life. The modern medicine mechanisms underlying this pain relief are thought to be related to the release of endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers, and the reduction of inflammatory markers.

Hormonal Balance

Endometriosis is often associated with hormonal imbalances, particularly an excess of estrogen. Acupuncture is believed to modulate hormonal levels by impacting the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, which plays a crucial role in regulating reproductive hormones. A harmonious hormonal balance can help in managing endometriosis symptoms and reducing the progression of endometrial lesions. However, most studies show that acupuncture increases estrogen levels. So, this is a bit contradictory other than to say that other acupuncture-induced mechanisms influencing hormonal balance and homeostasis may be in play.

Improved Blood Flow

Acupuncture is known to enhance blood circulation to the pelvic area, which can be beneficial for endometriosis patients. Improved blood flow can help reduce inflammation and promote the healing of endometrial lesions. This enhanced circulation can also alleviate the ischemia and hypoxia conditions commonly found in endometriotic tissues, potentially reducing the development of new lesions.

Reduced Stress and Anxiety

Living with chronic pain and other symptoms of endometriosis can lead to increased stress and anxiety. Acupuncture is reputed to mitigate stress and anxiety by modulating the activity of the amygdala and other brain regions associated with emotion regulation, promoting relaxation and mental well-being.

Empirical Evidence

Several studies and clinical trials have substantiated the efficacy of acupuncture in managing endometriosis symptoms. A systematic review by Zhu et al. (2011) concluded that acupuncture could be considered an effective and safe alternative for relieving endometriosis-related pain. Another study by Rubi-Klein et al. (2010) demonstrated that acupuncture reduces the severity and duration of pain during menstruation in women with endometriosis.

Integration with Conventional Treatment:

While acupuncture demonstrates the potential to alleviate endometriosis symptoms, it is crucial to view it as a complementary therapy. It is not a standalone treatment option for endo. Integrating acupuncture with conventional medical treatments, such as hormonal therapy, non-narcotic pharmaceuticals, and excisional surgery, can offer a holistic approach to managing endometriosis. This integrative approach can address both the physiological symptoms and the psychological stress associated with the condition, improving the overall quality of life for patients.

Read more: Integrative Therapies for Endometriosis

Limitations and Considerations

While acupuncture offers promising benefits for endometriosis, limitations exist, including the variability in acupuncture techniques and the lack of standardized treatment protocols. Moreover, the effectiveness of acupuncture may be influenced by individual differences, necessitating personalized treatment plans. It is essential for patients to consult with experts in this field to determine the appropriateness of acupuncture based on their medical history and specific circumstances.

Conclusions

Acupuncture emerges as a valuable complementary therapy for endometriosis, offering relief from pain, hormonal balance, improved blood flow, and reduced stress and anxiety. Empirical evidence substantiates its efficacy, and integrating it with conventional treatments can provide a comprehensive approach to managing endometriosis. However, individual variability and the lack of standardized protocols necessitate personalized treatment plans and consultation with experts in acupuncture as well as endo specialists. As research continues to unravel the mechanisms underlying acupuncture’s therapeutic effects, it holds the promise of enhancing the quality of life for individuals grappling with endometriosis.

References:

Wayne, P.M., et al. (2008). Acupuncture for pelvic and back pain in pregnancy: a systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 198(3), 254-259.

Zhu, X., et al. (2011). Acupuncture for pain in endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9), CD007864.

Rubi-Klein, K., et al. (2010). Is acupuncture in addition to conventional medicine effective as pain treatment for endometriosis? A randomised controlled cross-over trial. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 153(1), 90-93.

Lund I, Lundeberg T (2016). Is acupuncture effective in the treatment of pain in endometriosis? J Pain Res; 9: 157–165.

Endometriosis and Its Implications on Early Menopause: A Comprehensive Insight

Endometriosis, a chronic inflammatory condition, has been studied for its severe impact on women’s reproductive health in some aspects more than others. One area that has been relatively understudied is the connection between endometriosis and early menopause. This article will delve into the intricate relationship between endometriosis and early menopause, exploring the latest research studies, the associated risk factors, and the potential implications for women’s health.

Table of contents

- I. Understanding Endometriosis

- II. The Enigma of Early Menopause

- III. The Intersection of Endometriosis and Early Menopause

- IV. Recent Studies on Endometriosis and Early Menopause

- V. Key Findings From the Studies

- VI. Factors Influencing the Association

- VII. Implications of the Findings

- VIII. Limitations and Future Research

- IX. Coping With Endometriosis and Early Menopause

- X. Conclusion

I. Understanding Endometriosis

Endometriosis is an often painful condition in which tissue similar to the one lining the inside of the uterus — the endometrium — grows outside the uterus, typically on the ovaries, Fallopian tubes, and the tissue lining the pelvis. In some cases, it can spread beyond the pelvic area. Endo mostly affects women during their childbearing years and may also lead to fertility problems.

Read more: What causes endometriosis?

II. The Enigma of Early Menopause

Early menopause, also known as premature menopause or early natural menopause (ENM), is defined as the cessation of menstrual periods before the age of 45. This condition can have a profound impact on a woman’s life, affecting her fertility, cardiovascular health, cognitive function, and overall mortality rate. The main driver is premature ovarian failure (POF) or insufficiency (POI). Without proper levels of estrogen and progesterone, among other hormones, and highly coordinated hormonal fluctuations, menses cease. Menses can also cease due to direct damage to the uterine endometrial lining, but that is far less common. In this latter situation, in contrast to ovarian insufficiency, there are no symptoms of hot flashes or mood swings and the like.

Read more: Endometriosis And Menopause: Everything You Need To Know

III. The Intersection of Endometriosis and Early Menopause

The potential implications of endometriosis on early menopause have not been extensively researched. There is a need for more comprehensive studies to understand the intricate associations and mechanisms linking these two conditions.

IV. Recent Studies on Endometriosis and Early Menopause

Recent investigations have shed light on the possible association between endometriosis and early menopause. These studies suggest that women with endometriosis may be at a higher risk of experiencing early menopause, even after adjusting for various demographic, behavioral, and reproductive factors.

V. Key Findings From the Studies

The studies indicate a statistically significant association between endometriosis and early menopause. Women with endometriosis, particularly those who never used oral contraceptives and are nulliparous, may have a heightened risk of experiencing a shortened reproductive lifespan.

Studies focusing on premature ovarian failure (POF) or insufficiency (POI) suggest that this, in and of itself, is highly heterogeneous and related to mutations in more than 75 genes. Some of these mutations overlap with those associated with endometriosis, particularly in the range of inflammatory autoimmune disorders.

VI. Factors Influencing the Association

Multiple shared clinical factors may influence the association between endometriosis and early menopause, including body mass index (BMI), cigarette smoking, oral contraceptive use, parity, and history of infertility attributed to ovulatory disorder.

Given the genetic overlap of autoimmune and other disorders that influence POI and POF, it is quite probable that this is the root cause of the association between endometriosis and early menopause. However, this remains to be scientifically validated.

In those patients with advanced endo, where ovaries are partially removed or badly, as in the case of large endometriomas, there may be a direct anatomic cause for POI and POF.

VII. Implications of the Findings

The findings of these studies have important implications for women’s health. They suggest that women with endometriosis may need to consider the potential risk of early menopause in their reproductive planning. Additionally, healthcare providers may need to consider these findings when developing individualized treatment plans for women with endometriosis. A full evaluation should include screening for autoimmune disorders and possible genetic analysis for associated conditions.

VIII. Limitations and Future Research

While these findings are significant, they are also limited by certain factors, including the reliance on self-reported data and the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the study populations. Future research should aim to address these limitations and further explore the clinical and genetic or molecular association between endometriosis and early menopause.

IX. Coping With Endometriosis and Early Menopause

Living with endometriosis and dealing with early menopause can be challenging. However, understanding the connection between these conditions and seeking timely medical advice can help women manage their symptoms and maintain their quality of life. The first step is evaluation and management by providers who have specific and focused expertise in managing endometriosis.

Read more: Navigating HRT for Menopause in Women with Endometriosis

X. Conclusion

The association between endometriosis and early menopause is a significant area of women’s health that mandates further exploration. While recent studies suggest a potential link, more comprehensive research is needed to fully understand the implications of this association. In the meantime, it is crucial for women with endometriosis to be aware of the potential risk of early menopause and to seek expert consultation with endometriosis specialists.

References:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35061039/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5327623/

Postmenopausal Malignant Transformation of Endometriosis

Table of contents

Endometriosis is a pain and infertility producing condition which predominantly affects premenopausal women. Estimates suggest that up to 10% of women worldwide suffer from the condition during their reproductive years. While the incidence of postmenopausal endometriosis is considerably lower, studies have suggested that this may still be in the neighborhood of 2.5%. So it is a misconception that endo is exclusively a disease of younger women.

Further, although endometriosis is a benign disorder, there lies a risk of malignant transformation, at all ages. This article delves into the potential for malignant transformation of postmenopausal endometriosis.

Understanding Endometriosis and Menopause

Postmenopausal endometriosis refers to the occurrence or continuation of endometriosis symptoms after menopause, which typically occurs around age 50. This is defined as the cessation of menstrual cycles for twelve consecutive months. After this point, the ovaries produce minimal estrogen, a hormone which is generally considered essential for endo growth. So, without this hormone, or lowered levels, most cases of endometriosis naturally diminish. Yet, for some postmenopausal women, endometriosis can persist or even manifest anew.

The cause or causes of endometriosis in younger women are controversial and incompletely defined. Through uncertain but likely multifactorial mechanisms, endometriosis is characterized by the presence and growth of ectopic endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. While one might assume that a hypoestrogenic state associated with menopause would alleviate endometriosis, this isn’t always the case.

In postmenopausal women, the causes of endometriosis are less clear. Some contributing factors include:

- Residual Disease: Endometriosis that began before menopause may continue after menopause due to residual disease and growth stimulated by factors other than estrogen or high sensitivity to low estrogen levels.

- Exogenous Estrogen: Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) can potentially stimulate the growth of endometrial cells. This may be particularly relevant for postmenopausal women who take estrogen-only HRT, which can reactivate endometrial implants or even initiate new growths.

- Endogenous Estrogen Conversion: Adipose (fat) tissue can produce estrogen by converting it from other hormones. Postmenopausal women with higher amounts of adipose tissue might produce enough estrogen to promote the growth of endo. Fat can also store xeno-estrogens from certain toxins and then slowly release them into circulation. The tissue microenvironment around endometriosis lesions also contributes to local estrogen production.

Malignant Transformation: A Rare but Possible Event

While endometriosis is overwhelmingly benign, studies have indicated that women with endometriosis have an increased risk of developing certain types of ovarian cancers, specifically clear cell and endometrioid carcinomas.

Some factors that might increase the risk include:

- Duration of Endometriosis: Prolonged presence of endometriosis lesions might increase the risk of malignant transformation. In general, cancer risk increases with age and it is well known that chronic inflammation contributes to formation of cancer. Endo is inflammatory in nature. Thus, if endo is still growing after menopause this means more time in an inflammatory state, hypothetically contributing to the risk.

- HRT Use: As mentioned, exogenous estrogen can stimulate endometriosis growth, potentially increasing the risk of malignant changes in existing lesions. This is not proven but may be a contributory factor which is very complicated due to individual variations in receptor activity and levels of estrogen.

- Genetic Factors: Some genetic mutations might predispose women to both deeply invasive endometriosis and ovarian cancer, and there is overlap. Epigenetic factors regulate which genes turn on an off during life and are influenced by environmental factors. There is also a potential cumulative effect in the number of active mutated genes over the years. Some of the key genetic factors include:

- PTEN: PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene. Its mutations have been identified in both endometriosis and endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancers. Loss of PTEN function can lead to uncontrolled cell growth and might play a role in the malignant transformation of endometriosis.

- ARID1A: ARID1A mutations are frequently seen in endometriosis-associated ovarian cancers. This gene is involved in chromatin remodeling, and its mutation can lead to disruptions in DNA repair and subsequent malignant transformation.

- KRAS and BRAF: Mutations in these genes are known to play roles in the pathogenesis of various cancers. They’ve been identified in benign endometriotic lesions and might contribute to the early stages of malignant transformation.

- Inherited Genetic Mutations: Women with inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, known for their association with breast and ovarian cancers, might also have an increased risk of developing endometriosis and its subsequent malignant transformation.

Conclusions

Postmenopausal endometriosis, although less common than its premenopausal counterpart, cannot be overlooked. The absolute risk of malignant transformation, albeit very low, emphasizes the importance of regular monitoring and endo specialist consultations for postmenopausal women with endometriosis or its symptoms. When postmenopausal endometriosis is suspected or diagnosed, especially if it is invasive and there are unusual symptoms or pelvic masses, a consultation with a gynecologic oncologist is also prudent.

References

Bulun SE. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):268-279.

Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, et al. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):385-394.

Luca Giannella, Chiara Marconi, Jacopo Di Giuseppe, et al. Malignant Transformation of Postmenopausal Endometriosis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers (Basel) 2021 Aug 10;13(16):4026.

Luca Giannella, Chiara Marconi, Jacopo Di Giuseppe, et al. The association between endometriosis and gynecological cancers and breast cancer: a review of epidemiological data. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123(1):157-163.

Sato N, Tsunoda H, Nishida M, et al. Loss of heterozygosity on 10q23.3 and mutation of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN in benign endometrial cyst of the ovary: possible sequence progression from benign endometrial cyst to endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Cancer Res. 2000;60(24):7052-7056.

Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(16):1532-1543.

Dinulescu DM, Ince TA, Quade BJ, Shafer SA, Crowley D, Jacks T. Role of K-ras and Pten in the development of mouse models of endometriosis and endometrioid ovarian cancer. Nat Med. 2005;11(1):63-70.

Saha R, Pettersson H, Svedberg P, et al. Endometriosis and the risk of ovarian and endometrial adenocarcinomas: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4):e034760.

Can Endometriosis Become Malignant After Menopause?

Endometriosis, a condition commonly affecting women of reproductive age, doesn’t just vanish in menopause. In fact, an estimated 2-4% of postmenopausal women suffer from symptomatic endometriosis. Although endometriosis is generally benign, there lies a risk of malignant transformation. This article delves into the malignant transformation of postmenopausal endometriosis, presenting a comprehensive analysis of the topic.

Table of contents

Understanding Endometriosis and Menopause

Endometriosis is a complex clinical syndrome characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial-like tissue. This pathological condition primarily affects women of reproductive age, often causing infertility and chronic pelvic pain leading to severe functional limitations.

While one might assume that the cessation of menstruation and the hypoestrogenic state associated with menopause would alleviate endometriosis, this isn’t always the case. Postmenopausal endometriosis can affect up to 4% of women. Recurrences or malignant transformations, although rare, are possible events.

Malignant Transformation: A Rare but Possible Event

While endometriosis is a benign condition, it carries a risk of malignant transformation. Approximately 1% of ovarian endometriosis can turn into cancer. However, a prospective study found a standardized incidence ratio of malignant transformation of 8.95, indicating that malignant transformation, while rare, is a serious concern.

In the case of postmenopausal endometriosis, malignant transformation is even rarer. There are no definitive percentages about its prevalence, with data derived from studies, including case reports and case series. This scarcity of data highlights the need for further research into this topic.

Recurring Clinical Conditions

In the malignant transformation of postmenopausal endometriosis, some clinical conditions tend to recur:

- History of endometriosis

- Definitive gynecological surgery before menopause

- Estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for a relatively long time

These conditions, however, have shown a significant decrease in recent years. This decrease could be due to changes in the attitudes and management of gynecologists, influenced by up-to-date scientific evidence about the use of major surgery in gynecological pathologies.

The Role of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT)

HRT plays a significant role in postmenopausal endometriosis. Among the women who used HRT, estrogen-only therapy was taken by approximately 75% of women. The duration of treatment had a median of 11 years, with the course of treatment exceeding five years in most women.

Current recommendations on HRT include continuous combination formulations or Tibolone for women with previous endometriosis. However, these recommendations are based on limited data, emphasizing the need for more extensive studies on this topic.

Cancer Lesion Characteristics and Treatment

The malignant transformation of endometriosis can present with varying characteristics and may require different treatment approaches. Approximately 70% of cases had histology of endometrioid adenocarcinoma or clear cell carcinoma. The most frequent localization of the lesions was at the level of the pelvis, ovary, and vagina.

Most women underwent surgical treatment, with procedures including excision of the mass, hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and surgical debulking. Adjuvant medical treatment was performed in about 60% of cases.

Patient Outcomes and Follow-up

The outcomes for patients with malignant transformation of postmenopausal endometriosis are generally favorable. The survival rate is approximately 80% in 12 months, with a recurrence rate of 9.8% and a death rate of 11.5%.

The duration of follow-up had a median of 12 months. However, follow-up data is still too incomplete to provide adequate information on the prognosis, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

Conclusions

The malignant transformation of postmenopausal endometriosis presents a clinical challenge that requires further exploration. As gynecologists’ attitudes and management strategies evolve, it’s crucial to continue research into this area, to provide accurate and individualized evaluation and information for patients.

While endometriosis is generally a benign condition, the risk of malignant transformation, particularly in postmenopausal women, should not be overlooked. Comprehensive understanding and timely management of this condition are crucial to improving patient outcomes.

Reference:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34439184/

The Hidden Connection Between Systemic Lupus and Endometriosis

Based on possible shared characteristics and pathogenesis the interconnectedness of various ailments becomes a focal point of research. Such is the relationship between endometriosis and lupus, two seemingly unrelated conditions that share intriguing parallels. This article aims to shed light on the increased risk of being diagnosed with endometriosis in patients suffering from Systemic Lupus Erythematosus or SLE. The purpose of unraveling connections is that this may lead to treatment discoveries.

Table of contents

Understanding Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a multifaceted disease that primarily affects women in their reproductive years. It is characterized by the abnormal growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, leading to chronic pelvic pain, and potential infertility.

The pathophysiology of endometriosis involves a systemic inflammatory response, influenced by female sex hormones that may subtly affect the maintenance of immunity or the development of autoimmune diseases.

Getting to Know Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

SLE is a chronic, autoimmune disease that can affect various parts of the body, including the skin, joints, kidneys, heart, and lungs. It involves the immune system attacking the body’s own tissues, leading to inflammation and damage. Women, especially of childbearing age, are more frequently diagnosed with SLE than men. Other factors such as ethnicity, age of onset, and socioeconomic class significantly influence SLE incidence, with notable geographic differences observed.

Endometriosis and SLE: The Intriguing Association

Epidemiological studies suggest a solid link between endometriosis and female-dominant autoimmune diseases. However, not all studies support a significant association between endometriosis and SLE. The potential for spurious associations due to small study sizes and suboptimal control selection is high.

Unraveling the Connection: A Comprehensive Study

Given these inconsistencies, and accepting that the findings may not be applicable to all geo-ethnic populations, a large nationwide retrospective cohort study was conducted to assess the risk of endometriosis in women diagnosed with SLE. The study analyzed data from the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Research Database 2000 (n = 958,349) over a 13-year follow-up period (2000–2013).

Study Design and Population

The study adopted a retrospective cohort design with primary data sourced from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). The study cohort included women diagnosed with SLE between 1997 and 2013, and the index date was defined as the first diagnosis of SLE.

Assessed Outcome

The primary outcome was defined as the diagnosis of endometriosis. Given the lack of non-invasive diagnostic tools for endometriosis, the disease’s diagnosis was derived from clinical evidence or surgical intervention. Every effort was made to optimize parameters of non-surgical diagnosis of endo but surgical validation was lacking in a large number of subjects, representing a significant study weakness.

Results and Implications

The study, within stated limitations, found a statistically significant association between SLE and endometriosis, after controlling for age.

Conclusion: A Call for Further Research

The risk of endometriosis was found to be significantly higher in SLE patients compared to the general population in this study. This adds substantially to the overall body of evidence supporting an association. However, more research is needed to fully understand this association and to determine if it can be generalized across different geo-ethnic populations. Clearly, more basic science research is also critically needed to support epidemiologic associations.

Reference:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35922461/

Can endometriosis cause miscarriage? Understanding Endometriosis and Its Impact on Miscarriage

Endometriosis is a prevalent health condition, affecting approximately 10% of women worldwide. It is often associated with chronic pain and infertility, but its potential connection to miscarriage is not as widely recognized. This article aims to shed light on the link between endometriosis and miscarriage, drawing on recent scientific research and expert insights.

Table of contents

What is Endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a chronic condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus, known as endometrium, grows outside the uterus. This tissue can grow on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or the lining of the pelvic cavity. Just as the inner lining of the uterus thickens, breaks down, and bleeds with each menstrual cycle, so too does the endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. However, this displaced tissue has no way to exit the body, leading to various problems.

Read More: What causes endometriosis?

Pathogenesis of Endometriosis

Endometriosis develops in stages, with severity ranging from minimal to severe. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine groups endometriosis into four stages: minimal (Stage I), mild (Stage II), moderate (Stage III), and severe (Stage IV). The stages reflect the extent, location, and depth of endometrial-like tissue growth, as well as the presence and severity of adhesions and the presence and size of ovarian endometriomas.

Symptoms of Endometriosis

While some women with endometriosis may have no symptoms, others may experience:

- Painful periods

- Pain during intercourse

- Pain with bowel movements or urination

- Excessive bleeding

- Infertility

- Other signs and symptoms such as fatigue, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, or nausea

Read more: 20 Signs and Symptoms of Endometriosis

Endometriosis and Pregnancy Complications

Endometriosis has long been associated with infertility, with studies indicating that up to 50% of women with infertility have the condition. However, less is known about its impact on women who do conceive. Emerging research suggests that endometriosis may increase the risk of several pregnancy complications, including preterm birth, cesarean delivery, and miscarriage.

Read More: How Does Endometriosis Cause Infertility?

Endometriosis and Miscarriage: Understanding the Connection

Recent research has begun to explore the potential link between endometriosis and miscarriage. Miscarriage, also known as spontaneous abortion, is defined as the loss of a pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation. It is estimated that about 10-20% of known pregnancies end in miscarriage. The actual number is likely higher, as many miscarriages happen so early in pregnancy that a woman might not even know she’s pregnant.

The Role of Inflammation

One theory proposes that the inflammation associated with endometriosis could interfere with the early stages of pregnancy. Endometriosis is characterized by chronic pelvic inflammation, which could potentially disrupt the implantation of the embryo or the development of the placenta.

The Impact of Surgical Treatment

Another factor to consider is the potential impact of surgical treatment for endometriosis. There have only been a few clinical trials and they do not indicate that surgical excision reduces the risk of miscarriage. However, there are two very large databases from Sweden and Scotland that suggest a benefit to removing known endometriosis to lower pregnancy loss risk. More research is required.

Hormonal Factors

Endometriosis can alter the hormonal environment of the uterus, which could potentially impact early pregnancy. More research is needed to fully understand how these hormonal changes might contribute to miscarriage risk.

Research Insights: Endometriosis and Miscarriage Risk

Several studies have investigated the link between endometriosis and miscarriage. A meta-analysis published in 2020 in the journal BioMed Research International found that women with endometriosis had a significantly higher risk of miscarriage compared to women without the condition. This risk was particularly pronounced in women who conceived naturally, rather than those with tubal infertility who conceived through assisted reproductive technology (ART).

Coping with Endometriosis and Miscarriage

The potential link between endometriosis and miscarriage can come as distressing news. However, it’s important to remember that many women with endometriosis have successful pregnancies. So, counseling and intervention really depend on the individual situation. With repeat losses, there are many potential reasons but it appears that endo can be one of them.

Read more: Find an Endometriosis Specialist for Diagnosis, Treatment, & Surgery.

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a complex condition that can impact various aspects of a woman’s health, including her fertility and pregnancy outcomes. While research suggests a potential link between endometriosis and miscarriage, many women with the condition have successful pregnancies. If you have endometriosis or suspect you have endo, and having difficulty conceiving or experiencing pregnancy losses, it’s crucial to seek consultation with an endometriosis specialist.

Reference:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33490243/

Epigenetics and Endometriosis Hereditary: Unraveling the Complex Web of Hereditary Implications

Endometriosis, a medical condition afflicting numerous women worldwide, continues to puzzle medical researchers due to its complex nature and the myriad of genetic and environmental factors contributing to its development. This article aims to dissect the convoluted genetic aspect of endometriosis, providing a comprehensive understanding of its hereditary implications.

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction to Endometriosis

- 2. The Puzzle of Endometriosis Hereditary

- 3. Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis

- 4. The Genetic/Epigenetic Theory: A Closer Look

- 5. Clinical Implications of the Genetic/Epigenetic Theory

- 6. Prevention and Treatment of Endometriosis: A Genetic/Epigenetic Perspective

- 7. Conclusion

1. Introduction to Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a condition characterized by the growth of endometrium-like tissue outside the uterus. This disease exhibits significant diversity in its manifestation, with the tissue appearing in various forms and locations. It has a significant impact on the quality of life of the affected individual, often causing pain, infertility, and other related complications.

2. The Puzzle of Endometriosis Hereditary

2.1 Hereditary Factors in Endometriosis

Endometriosis has been confirmed as a hereditary disease, with the risk of developing the condition significantly higher in first-degree relatives of affected women. Twin studies further corroborate this, showing a similar prevalence and age of onset in twins. Despite this, the exact genetic mechanisms contributing to endometriosis remain elusive and likely presents with an inheritance pattern that is multifactorial.

2.2 Genetic and Epigenetic Incidents in Endometriosis

Genetic and epigenetic incidents, both inherited and acquired, significantly contribute to the development of endometriosis. These incidents, which can cause changes in gene expression, are often triggered by environmental factors such as oxidative stress and inflammation. Familial clustering of endometriosis has been shown in an array of studies with similar findings. First-degree relatives are 5 to 7 times more likely to have surgically confirmed disease.

Familial endometriosis may be more severe than sporadic cases. This also supports the multifactorial inheritance of endometriosis and a genetic propensity as it may spread more severely to offspring or siblings. These women with familial inheritance may also have earlier age of onset and symptoms.

3. Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis

3.1 The Implantation Theory

The implantation theory, popularized by Sampson in 1927, suggests that endometriosis is caused by the implantation of endometrial cells in locations outside the uterus. This theory, while reasonable, fails to explain certain observations, such as the occurrence of endometriosis in men and women without endometrium.

3.2 The Metaplasia Theory

The metaplasia theory postulates that endometriosis is a result of metaplastic changes, a process where one type of cell changes into another type due to environmental stress. This theory, while accounting for some observations, is limited by the varying definitions of “metaplasia” and the disregard for genetic or epigenetic changes.

3.3 The Genetic/Epigenetic Theory

The genetic/epigenetic theory proposes that endometriosis results from a series of genetic and epigenetic incidents, both hereditary and acquired. This theory is compatible with all known observations of endometriosis, providing a comprehensive understanding of the disease’s pathogenesis.

4. The Genetic/Epigenetic Theory: A Closer Look

4.1 Genetic and Epigenetic Incidents: The Triggers of Endometriosis

According to the genetic/epigenetic theory, endometriosis is triggered by a series of genetic and epigenetic incidents. These incidents can be hereditary, transmitted at birth, or acquired later in life due to environmental factors such as oxidative stress and inflammation.

4.2 The Role of Redundancy in the Development of Endometriosis

Redundancy, where a task can be accomplished by multiple pathways, plays a significant role in the development of endometriosis. This redundancy can mask the effects of minor genetic and epigenetic changes, causing them to become visible only when a higher capacity is needed.

4.3 The Genetic/Epigenetic Theory and Endometriosis Lesions

Endometriosis lesions are clonal, meaning they originate from a single cell that has undergone genetic or epigenetic changes. The genetic/epigenetic theory proposes that these lesions can remain dormant for extended periods, similar to uterine myomas, and may only be reactivated by certain triggers such as trauma.

5. Clinical Implications of the Genetic/Epigenetic Theory

5.1 Understanding the Nature of Endometriosis Lesions

According to the genetic/epigenetic theory, most subtle or microscopic lesions are normal endometrium-like cells that would likely resolve without intervention. In contrast, typical, cystic, and deep lesions are benign tumors that do not recur after complete excision but may progress slowly or remain dormant for an extended period.

5.2 The Role of Factors in Endometriosis Hereditary

The genetic/epigenetic theory suggests that genetic and epigenetic defects inherited at birth may play a significant role in the development of endometriosis. These hereditary factors may not only contribute to the disease’s onset but also to associated conditions such as subfertility and pregnancy complications.

5.3 Variability in Endometriosis Lesions

The genetic/epigenetic theory explains that endometriosis lesions can vary significantly in their reaction to hormones and other environmental factors. This variability is due to the specific set of genetic and epigenetic changes present in each lesion.

6. Prevention and Treatment of Endometriosis: A Genetic/Epigenetic Perspective

6.1 Prevention of Genetic/Epigenetic Incidents

Preventing the genetic/epigenetic incidents that trigger endometriosis can be a complex task. However, reducing repetitive stress may be useful in this regard.

6.2 Treatment of Endometriosis

The genetic/epigenetic theory suggests that the treatment of endometriosis should focus on the complete excision of the lesions to prevent recurrence. However, it also proposes that less radical surgery may be sufficient in some cases where the surrounding fibrosis and outer cell layers are composed of normal cells with reversible changes.

7. Conclusion

While the genetic/epigenetic theory provides a comprehensive understanding of the pathogenesis of endometriosis, it remains a theory until disproven by new observations. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms contributing to endometriosis, paving the way for more effective prevention and treatment strategies. Despite the complexity and challenges, the pursuit of knowledge in this field continues, offering hope for a future where endometriosis can be effectively managed and potentially prevented.

Reference:

- Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, Wattiez A, Gomel V, Martin DC. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil Steril. 2019 Feb;111(2):327-340. [PubMed]

- Simpson J, Elias S, Malinak L, et al. Heritable aspects of endometriosis: 1. Genetic studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;137:327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Hadfield R, Mardon H, Barlow D. Age of onset of pain symptoms in non-twin sisters concordant for endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:403–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

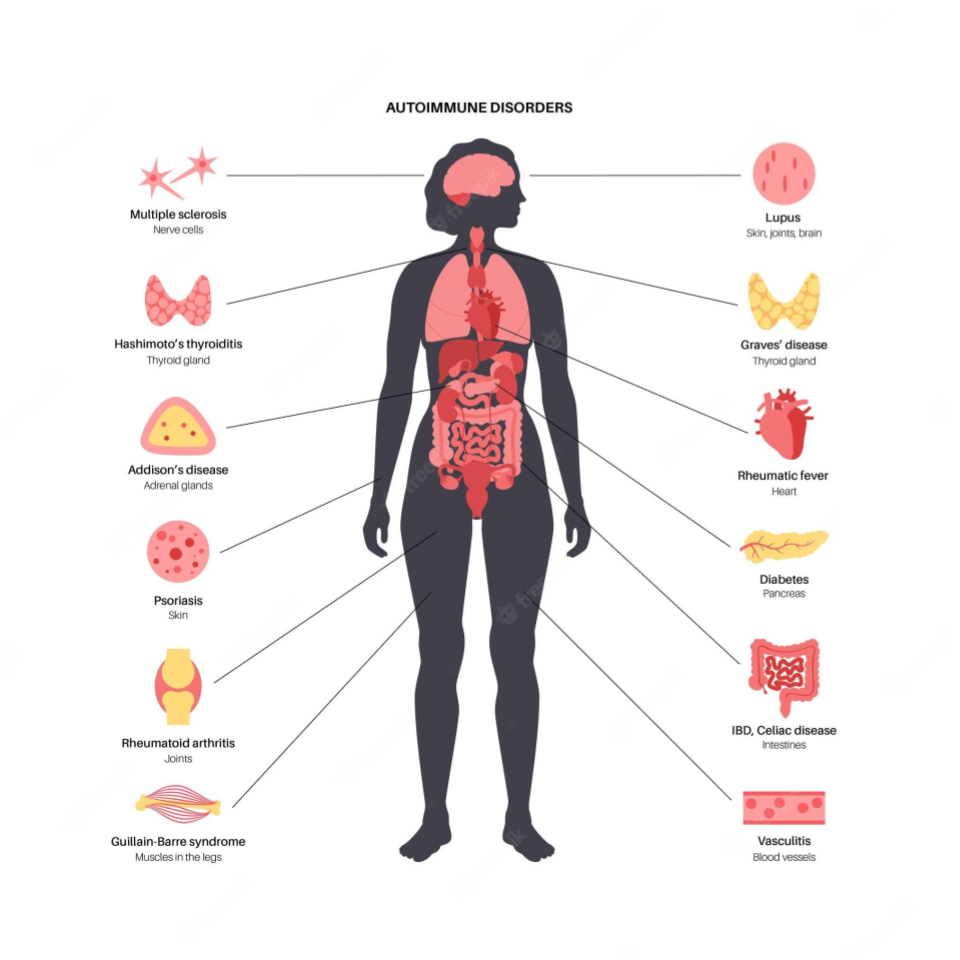

Unraveling the Connection Between Endometriosis and Autoimmune Diseases

Endometriosis causes pain, multiple bowel symptoms and infertility, among many other debilitating symptoms, in about 10% of women, mostly in the reproductive age range. Developing research has shown that there is a link to various autoimmune conditions.

Table of contents

- Understanding Endometriosis

- The Immune System’s Role

- Is Endometriosis an Autoimmune Disease?

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and Endometriosis

- Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS) and Endometriosis

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Endometriosis

- Autoimmune Thyroid Disorders (ATD) and Endometriosis

- Coeliac Disease (CLD) and Endometriosis

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and Endometriosis

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Endometriosis

- The Bigger Picture

- The Path Ahead

Understanding Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a chronic gynecological disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue growing outside the uterus. This means the cells look like those which line the inner part of the uterus but differ markedly in multiple ways at the molecular level. The more we find out the less it is clear what the origins are. However, they are likely partly genetic and partly based on other multiple influences of the environment on your body and genes.

The Immune System’s Role

Research suggests that abnormalities in the immune system may play a key role in the development of endometriosis. These abnormalities could prevent the immune system from effectively clearing ectopic endometrial cells, regardless of how they get there, allowing them to implant and grow outside the uterus. This hypothesis suggests that endometriosis might be, at least in part, an immunity-associated disorder.

Furthermore, endometriosis is often associated with a chronic inflammatory response, triggered by the presence of ectopic endometrial-like cells. This inflammation, coupled with the immune system’s inability to effectively remove ectopic cells, could partly explain the chronic pain often associated with endometriosis.

Is Endometriosis an Autoimmune Disease?

Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own cells, viewing them as foreign invaders. The link between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases is still being explored, but multiple studies suggest that women with endometriosis may have a higher risk for certain autoimmune diseases. It is not clear if endo carries a risk of developing autoimmune diseases or if the reverse is true or if they simply share common molecular mechanisms which results in both potentially occurring in any given individual. At this point it is important to stress that an “association” does not mean “cause”.

This review aims to delve into the current state of research on the association if endometriosis is an autoimmune disease. It presents key findings from population-based studies, discusses the potential implications, and highlights areas for future research.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and Endometriosis

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation and damage to various body tissues, including the skin, joints, kidneys, and heart. Some studies have suggested a positive association between endometriosis and SLE.

One study suggested a seven-fold increase in the odds of having SLE among women with endometriosis. However, the study relied on self-reported diagnoses, which may introduce bias. A more recent cohort study found a more modest but still significant elevation in SLE risk among women with endometriosis.

Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS) and Endometriosis

Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by dry eyes and mouth, often accompanied by other systemic symptoms. Several studies have investigated the potential link between SS and endometriosis.

A meta-analysis of three case-control studies found a 76% higher odds of SS in women with endometriosis. However, these studies had small sample sizes and wide confidence intervals, indicating a need for further research. Confidence intervals describe the range of results around a measurement which indicate how accurate the conclusion might be. The tighter it is among measurements the better.

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Endometriosis

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting many joints, including those in the hands and feet. Some studies have suggested a link between endometriosis and an increased risk of developing RA.

One meta-analysis, for example, found a 50% increased risk of RA among women with endometriosis. Again, the studies included in the analysis had limitations, including small sample sizes and wide confidence intervals.

Autoimmune Thyroid Disorders (ATD) and Endometriosis

Autoimmune thyroid disorders (ATDs), including Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, occur when the immune system attacks the thyroid gland, leading to either overactivity (hyperthyroidism) or underactivity (hypothyroidism) of the gland.

A meta-analysis of three case-control studies suggested a non-significant increase in the odds of ATD in women with endometriosis. However, the studies had high heterogeneity and low-quality scores, suggesting that further research is needed.

Coeliac Disease (CLD) and Endometriosis

Coeliac disease (CLD) is an autoimmune disorder where ingestion of gluten leads to damage in the small intestine. Some studies have suggested a possible link between endometriosis and CLD.

A meta-analysis of two case-control studies found a four-fold increase in the odds of CLD among women with endometriosis. Again, these studies had small sample sizes and wide confidence intervals, indicating a need for further research.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and Endometriosis

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease that attacks the central nervous system. Current research on the association between MS and endometriosis is limited and inconclusive, with some studies suggesting a possible link while others finding no significant association.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Endometriosis

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Some studies indicate a possible association between IBD and endometriosis.

One study found a 50% increase in the risk of IBD among women with endometriosis. However, the study had a small sample size and the confidence interval was wide, indicating a need for further research.

The Bigger Picture

While the evidence for an association between endometriosis and certain autoimmune diseases is compelling, it’s important to emphasize that correlation or association does not imply causation. Further research is needed to determine whether endometriosis actually increases the risk of developing autoimmune diseases or vice versa, or whether the two share common risk factors or underlying mechanisms.

The potential link between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases highlights the importance of a comprehensive approach to women’s health. For women with endometriosis, being aware of the potential increased risk of autoimmune diseases can inform their healthcare decisions and monitoring.

The Path Ahead

The intersection of endometriosis and autoimmune diseases is a complex and evolving field of research. Better understanding the relationship between these conditions could help improve diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately, the quality of life for patients with endometriosis.

By continuing to explore this connection, we are gaining new insights into the pathophysiology of endometriosis and autoimmune diseases, potentially leading to novel treatments and preventive strategies.

Reference:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6601386/

Navigating HRT for Endometriosis and Menopause in Women

Endometriosis, a chronic condition, is often associated with the fertile years of a woman’s life. But what happens when these women reach menopause? Can the symptoms of endometriosis persist, or even worsen, during this transition? This article aims to shed light on these questions and provide guidance for women with a history of endometriosis approaching menopause.

Table of contents

- Understanding HRT and Endometriosis: A Quick Overview

- Endometriosis and Menopause: The Connection

- Recurrence of Endometriosis

- Malignant Transformation of Endometriotic Foci

- Should HRT be Given to Women with Previous Endometriosis?

- Should HRT be Given Immediately Following Surgical Menopause?

- What Menopausal Treatments for Women with Endometriosis?

- Conclusions and Guidance

Understanding HRT and Endometriosis: A Quick Overview

Endometriosis is a medical condition characterized by the growth of endometrial-like tissue (the tissue that lines the uterus) outside the uterus. This condition, affecting approximately at least 10% of women in their reproductive years, can lead to debilitating pain, infertility, and other complications. However, the diagnosis of endometriosis often gets delayed due to the non-specific nature of its symptoms and the lack of reliable diagnostic tools.

The exact cause of endometriosis remains unclear, but estrogen dependence, progesterone resistance, inflammation, environmental factors and genetic predisposition are some of the known contributing factors. The primary treatment and support options for endometriosis include hormonal therapy, pain management, pelvic floor physical therapy and excisional surgery.

Endometriosis and Menopause: The Connection

Menopause, the cessation of menstruation, is a natural phase in a woman’s life. It is commonly believed that endometriosis, an estrogen-dependent condition, resolves after menopause due to the decline in estrogen levels. However, this belief is being challenged as more cases of postmenopausal endometriosis are reported.

The persistence or recurrence of endometriosis after menopause can be attributed to multiple factors. One factor may be persistent higher levels of estrogen in some women. One common estrogen source is Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) to manage menopausal symptoms. HRT, which usually includes estrogen, may reactivate endometriosis in some cases. However, it is a complex interplay of estrogen, progesterone or progestins if they are included, receptor sensitivity and number and other molecular signaling factors, including the presence or absence of genomic alterations. It’s also important to keep in mind that endometriosis cells and their surrounding support cells can locally produce estrogen. Estrogen can also be generated by the interconversion of other hormones in your fat cells. So, taking hormonal replacement is not the only potential source of estrogen after menopause.

Numerous case reports and series have documented the recurrence of endometriosis or malignant transformation of endometriotic foci in postmenopausal women. In these reports, the majority of women had undergone surgical menopause (ovaries were removed) due to severe premenopausal endometriosis.

Recurrence of Endometriosis

In several case studies, postmenopausal women reported symptoms similar to those experienced during their premenopausal years. These symptoms included abnormal bleeding if the uterus was still intact and pain, often in the genitourinary system. Notably, all women who experienced recurrence were on some form of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), particularly unopposed estrogen therapy.

Malignant Transformation of Endometriotic Foci

Case studies have also reported instances of malignant transformation of endometriotic foci in postmenopausal women on HRT. These cases highlight the potential risk of exogenous estrogen in stimulating malignant transformation in women with a history of endometriosis. It’s critical to point out that this is rare and that is why these are case reports rather than large studies. When these steps towards malignant transformation have been found they are usually associated with genetic alterations like PTEN, TP53 and ARID1A. These alterations are more often found in deep infiltrating and endometrioma types of endometriosis, which are less common than the superficial variant.

Should HRT be Given to Women with Previous Endometriosis?