Endo diet: Mediterranean or FODMAP for the win?

A healthy eating pattern can be therapeutic and good for our health overall, but it can be difficult to decide on what is best for our bodies. The process can involve a long time spent in trial and error to find what works for our individual body and its needs. When looking at studies on dietary interventions, we find that they are difficult to perform- often ending up with strong bias or high inconsistent rates with adherence (anyone else here ever cheat on a diet??). But they can give us some direction. For instance, a systematic analysis by Nirgianakis et al. (2021) looked at a few recent studies on diet’s effect on endometriosis symptoms. While, unfortunately, the data was not strong enough for any strong conclusions, it can give some clues for individuals with endometriosis (along with consultation with a healthcare provider).

Two of the diets looked at included the Mediterranean diet and a diet low in fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP). Both showed promise for help with endometriosis symptoms, particularly gastrointestinal symptoms and pain.

Nirgianakis et al., (2021) explains:

“FODMAPs are poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates that are readily fermentable by bacteria. Their osmotic actions and gas production may cause intestinal luminal distension inducing pain and bloating in patients with visceral hypersensitivity with secondary effects on gut motility….Diseases like irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis come along with visceral hypersensitivity, implementing the hypothesis of symptom-reduction after sticking to a low-FODMAP diet. This is very important given the high prevalence of gastrointestinal-related symptoms and co-morbidities in patients with endometriosis. Interestingly, the low-FODMAP diet includes not only a low-Ni diet, but also a low-lactose and a low-gluten diet, thus covering the above-mentioned diets and a large spectrum of high-prevalence pathologies, such as lactose intolerance and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. It is therefore possible to obtain clinical benefits from a low-FODMAP diet, even if at the cost of probably not necessary dietary exclusions.”

The Mediterranean diet includes “fresh vegetables, fruit, white meat, fish rich in fat, soy products, whole meal products, foods rich in magnesium, and cold-pressed oils,” while avoiding “sugary drinks, red meat, sweets, and animal fats”. The review noted that “a significant relief of general pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and dyschezia as well as an improvement in the general condition was found.” Moreover, the “Mediterranean diet has well-known antioxidant effects. However, the Mediterranean diet does not involve just the supplementation of certain antioxidants, but rather a collection of eating habits and may thus improve endometriosis-associated pain via additional mechanisms. Fish as well as extra virgin olive oils have been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects. Specifically, extra virgin olive oil, which contains the substance oleocanthal, displays a similar structure to the molecule ibuprofen, and both take effect via the same mechanism, i.e., cyclooxygenase inhibition. Moreover, the increased amount of fibers provides a eupeptic effect while foods high in magnesium could prevent an increase in the intracellular calcium level and advance the relaxation of the uterus. Taking into account the lack of risks or side effects even after long-term lifetime adherence to this diet and the possible other general health benefits, clinicians may suggest this type of dietary intervention to patients with endometriosis who wish to change their nutritional habits.”

Finally, the authors looked at a qualitative study and found that “the participants experienced an increase in well-being and a decrease in symptoms following their dietary and lifestyle changes. They also felt that the dietary changes led to increased energy levels and a deeper understanding of how they could affect their health by listening to their body’s reactions.” So, taking control of your diet can help improve your general sense of well-being.

Again, there was not strong evidence from any of the studies reviewed, but it might prove helpful when discussing complementary therapies with your healthcare provider. You can find more information about diet and endometriosis here.

Reference

Nirgianakis, K., Egger, K., Kalaitzopoulos, D. R., Lanz, S., Bally, L., & Mueller, M. D. (2021). Effectiveness of Dietary Interventions in the Treatment of Endometriosis: a Systematic Review. Reproductive Sciences, 1-17. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43032-020-00418-w

Life altering disease and caregivers

Endometriosis can have a profound effect on a person’s ability to work, care for their home, care for their family, and even care for themselves- and this impacts their loved ones as well (Missmer et al., 2021). Endometriosis can have a “negative impact on intimate relationships” (Facchin et al., 2021). It is essential for the person with endometriosis and their support person(s) to have a plan to take care of both of themselves.

The impact endometriosis has on the activities of daily life is not well understood by the general population. This makes it difficult for even loved ones and family members to understand why you may be so fatigued or in too much pain some days to do what you might be able to other days- not to mention the emotional toll it can have. Education for loved ones about the disease itself is important as is education about the treatment. To “minimize the negative impact of endometriosis” on an individual’s life course, “early diagnosis and effective intervention in treating the disease” is imperative (Missmer et al., 2021). This is what we advocate for so strongly- early diagnosis and effective treatment to minimize the impact on a person’s life!

Once your support person or caregiver has a better understanding of the disease and its treatment, you can both develop a plan on how to handle its impact on your lives. Endometriosis can be life altering for those of us with it and those around us. It is important to address the way endometriosis affects our daily lives and have a plan to care for ourselves and our caregivers. This could be parents, partners, children, and various other loved ones involved in our lives. Each might have a different role to play and its good to have a collective plan to lessen the detrimental effects of endometriosis.

For those of us with endometriosis, remember it’s okay to need help. It is easy to feel guilty about not being able to do things, but don’t feel guilty for the effects of a chronic illness. You are doing the best you can. Accept help when it’s offered. Be realistic about what you need to live your best life possible where you are at. Borrowing from the Marine Corps, we have to improvise and adapt if we are to overcome. You are worth the effort.

For the caregivers in our lives- thank you. You’ll never know how much it means to have someone love, understand, and support us on this difficult journey. There are many of us who don’t have that support in our lives and are most acutely aware of how much it would mean. We want you to take care of yourself too. The following is for anyone who is in a caregiver role (including those of us with endometriosis who are in a caregiver role as well):

Being a support person or a caregiver can be both difficult and rewarding. When you start to feel the weight of it, there is a nursing diagnosis for it called “caregiver role strain” (Wayne, 2017). “While caregiving can be rewarding and positive, many family caregivers experience significant physical, psychological, and financial stressors in association with their caregiving role” (Wayne, 2017). This strain can come from multiple factors, such as unrealistic expectations (you won’t be able to fix us), juggling multiple roles (such as income earner, caregiver to other family members), lack of a support system (especially with a disease that others may not understand or may even trivialize), financial pressures, demands of care, social isolation, and neglecting your own well-being (FreedomCare, 2020).

From Wayne (2017), here are some things that might help with reducing caregiver role strain:

- Set aside time for yourself. Take care of your own physical and emotional needs. You can’t pour from an empty cup- you need time to rebuild your physical and emotional energy.

- Utilize stress-reducing methods- “It is important that the caregiver has the opportunity to relax and reenergize emotionally throughout the day to assume care responsibilities.”

- Participate in a support group if there is one available close by or online.

- Discuss problems, concerns, and feelings with a support person or a counselor. Sometimes you need someone outside the family to talk to. Taking on the caregiver role can change dynamics of the relationship and it can take effort to keep the “normal” relationship stuff going.

- Accept help! Ask and allow other available family and friends to assist with caregiving. “Successful caregiving should not be the sole responsibility of one person.”

- Make life chores easy on the both of you. For example, having occasional (or regular if you are able!) housekeeping services or deciding to get takeout food rather than cook one night can help relieve the burden sometimes. It’s okay if it’s not perfect.

Resources:

- Find more at: https://icarebetter.com/learning-library/patient-stories/

- Wondering if you are suffering from caregiver role strain? You can use the Modified Caregiver Strain Index to assess and talk to your healthcare provider about ways to help cope: https://www.sralab.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/issue-14.pdf

- Endowhat: “Caregivers” https://www.endowhat.org/caregivers

References

Facchin, F., Buggio, L., Vercellini, P., Frassineti, A., Beltrami, S., & Saita, E. (2021). Quality of intimate relationships, dyadic coping, and psychological health in women with endometriosis: Results from an online survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 146, 110502. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110502

FreedomCare. (2020). What is caregiver strain and how to avoid it. Retrieved from https://www.freedomcareny.com/posts/caregiver-role-strain

Missmer, S. A., Tu, F. F., Agarwal, S. K., Chapron, C., Soliman, A. M., Chiuve, S., … & As-Sanie, S. (2021). Impact of endometriosis on life-course potential: a narrative review. International Journal of General Medicine, 14, 9. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S261139

Wayne, G. (2017). Caregiver role strain nursing care plan. Retrieved from https://nurseslabs.com/caregiver-role-strain/

Insomnia and poor sleep with endometriosis

Sleep quality in individuals with endometriosis is significantly worse than those without it (Nunes et al., 2015). It seems like a no-brainer that pain and other symptoms from endometriosis can affect sleep quality. In fact, pain from endometriosis is known to affect a person’s “work/school, daily activities, exercise, and sleep to a moderate-extreme degree” (DiVasta et al., 2018). And in a vicious cycle, pain affects sleep and poor sleep affects pain. We get how pain can affect sleep, but what are the mechanics behind poor sleep affecting pain?

Ishikura et al. (2020) explains:

“It is well known that any pain condition can affect sleep, leading to sleep disturbances and impairment in sleep quality. In turn, sleep disruption can activate inflammatory mechanisms by triggering changes in the effector systems that regulate the immune system, resulting in abnormal increases in inflammatory responses that can stimulate or increase pain. This can result in the creation of a vicious cycle, with pain causing sleep disturbance that increases inflammation, leading to increased pain. Moreover, experimental studies have shown that the association of sleep loss and inflammatory markers are stronger in females than males, suggesting that women with both insomnia and endometriosis complaints are more susceptible to symptoms of pain. Endometriosis induces several debilitating symptoms that affect women´s lives, including insomnia; however, there have been very few studies of this association…. Treating insomnia would reduce the negative outcomes related to the inflammatory- and pain-related aspects of endometriosis and would contribute to an improvement in mental health and daytime function.”

This poor sleep can increase fatigue, affect quality of life, increase stress, and be detrimental to mental health in those with endometriosis (Arion et al., 2020; Ramin-Wright et al., 2018). Hormonal fluctuations within the menstrual cycle can affect sleep quality as well (drop in progesterone before menses, rise in body temperature during the luteal phase). Some hormonal treatments can affect sleep (Brown et al., 2008).

What can we do to help our sleep? Step one is to have a plan to address the underlying factors affecting sleep such as removing endometriosis. In the meantime, practice pain reduction techniques (nutrition,complimentary therapies such as yoga, pelvic physical therapy, etc.), practice good sleep hygiene, and talk to your healthcare provider about ways to manage pain and insomnia. One study indicated that “melatonin improved sleep quality” and “reduced the risk of using an analgesic by 80%” in patients with endometriosis (Schwertner et al., 2013). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2020) reports that cognitive behavioral therapy is the most effective therapy for chronic insomnia. They also suggest:

Keep a consistent sleep schedule. Get up at the same time every day, even on weekends or during vacations.

Set a bedtime that is early enough for you to get at least 7-8 hours of sleep.

Don’t go to bed unless you are sleepy.

If you don’t fall asleep after 20 minutes, get out of bed. Go do a quiet activity without a lot of light exposure. It is especially important to not get on electronics.

Establish a relaxing bedtime routine.

Use your bed only for sleep and sex.

Make your bedroom quiet and relaxing. Keep the room at a comfortable, cool temperature.

Limit exposure to bright light in the evenings.

Turn off electronic devices at least 30 minutes before bedtime.

Don’t eat a large meal before bedtime. If you are hungry at night, eat a light, healthy snack.

Exercise regularly and maintain a healthy diet.

Avoid consuming caffeine in the afternoon or evening.

Avoid consuming alcohol before bedtime.

Reduce your fluid intake before bedtime.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2020)

References

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2020). Healthy sleep habits. Retrieved from https://sleepeducation.org/healthy-sleep/healthy-sleep-habits/

Arion, K., Orr, N. L., Noga, H., Allaire, C., Williams, C., Bedaiwy, M. A., & Yong, P. J. (2020). A quantitative analysis of sleep quality in women with endometriosis. Journal of Women’s Health, 29(9), 1209-1215. Retrieved from https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jwh.2019.8008

Brown, S. G., Morrison, L. A., Larkspur, L. M., Marsh, A. L., & Nicolaisen, N. (2008). Well-being, sleep, exercise patterns, and the menstrual cycle: a comparison of natural hormones, oral contraceptives and depo-provera. Women & health, 47(1), 105-121. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v47n01_06

DiVasta, A. D., Vitonis, A. F., Laufer, M. R., & Missmer, S. A. (2018). Spectrum of symptoms in women diagnosed with endometriosis during adolescence vs adulthood. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 218(3), 324-e1. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.007

Ishikura, I. A., Hachul, H., Pires, G. N., Tufik, S., & Andersen, M. L. (2020). The relationship between insomnia and endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 16(8), 1387-1388. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8464

Nunes, F. R., Ferreira, J. M., & Bahamondes, L. (2015). Pain threshold and sleep quality in women with endometriosis. European Journal of Pain, 19(1), 15-20. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.514

Ramin-Wright, A., Schwartz, A. S. K., Geraedts, K., Rauchfuss, M., Wölfler, M. M., Haeberlin, F., … & Leeners, B. (2018). Fatigue–a symptom in endometriosis. Human reproduction, 33(8), 1459-1465. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey115

Schwertner, A., Dos Santos, C. C. C., Costa, G. D., Deitos, A., de Souza, A., de Souza, I. C. C., … & Caumo, W. (2013). Efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of endometriosis: a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. PAIN®, 154(6), 874-881. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S030439591300081X

What’s all the buzz about the bowel?

The bloating, cramping, diarrhea, constipation, pain with bowel movements, nausea…could this be endometriosis?

Yes, it could.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) like symptoms are common with endometriosis- up to 85% of endometriosis patients have gastrointestinal/bowel symptoms (Aragon & Lessey, 2017; Ek et al., 2015). It can be difficult to distinguish if it is endometriosis causing the IBS-like symptoms or if IBS is occurring along with endometriosis. Ek (2019) noted that “several potential shared pathophysiological mechanisms exist between endometriosis and IBS, such as chronic low-grade inflammation, increased mast cell numbers, increased mast cell activation, visceral hypersensitivity, altered gut microbiota and increased intestinal permeability, which has been described in relation to both endometriosis and IBS.” IBS symptoms can be helped with a low FODMAPs diet, and studies have noted that those with both IBS type symptoms AND endometriosis found improvement with a low FODMAPs diet (Moore et al., 2017). (See more info on bowel/GI endometriosis)

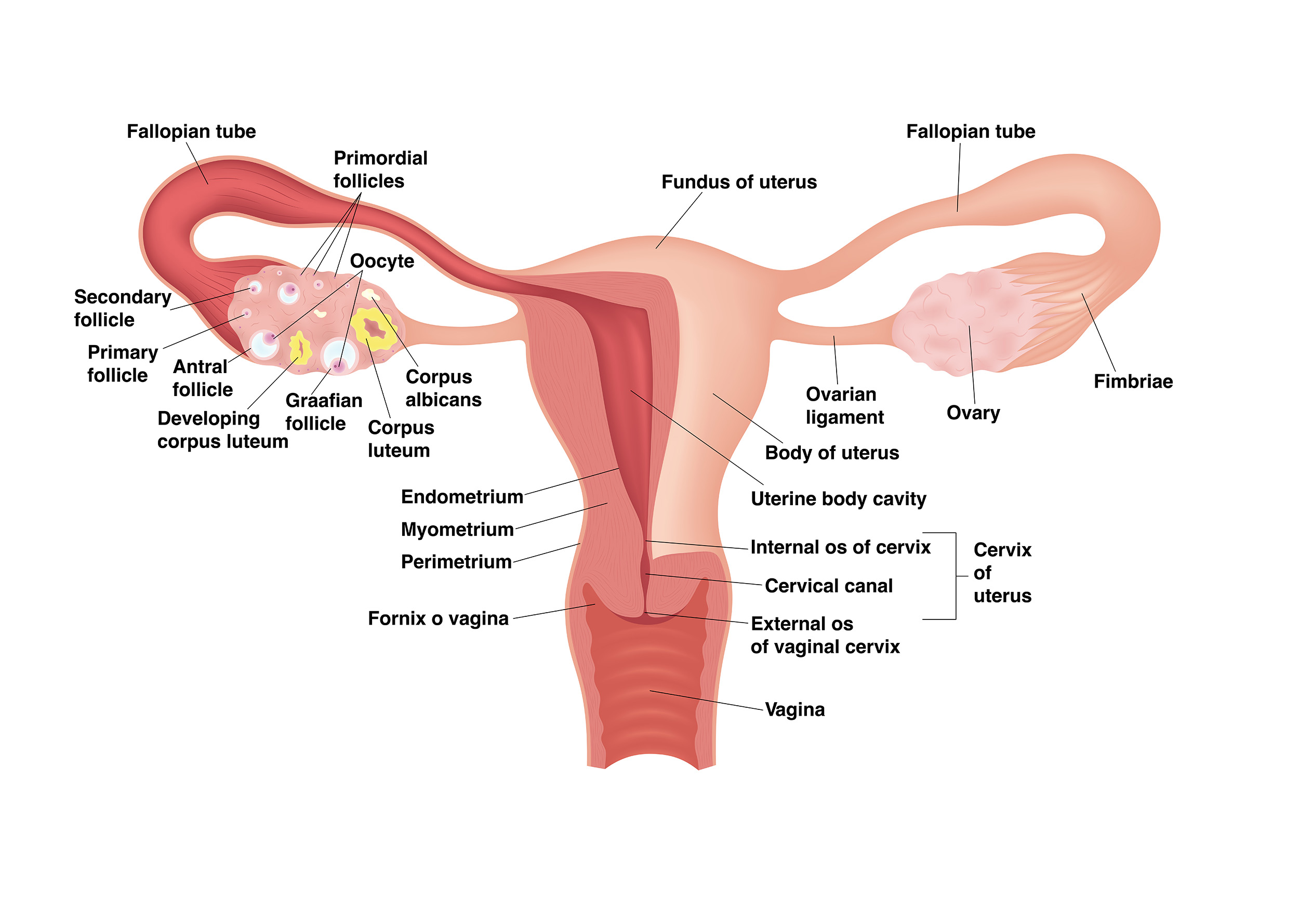

Endometriosis does not have to be on the bowel to cause bowel symptoms. Most of the time, symptoms may be due to irritation from lesions near the bowel (such as posterior cul de sac, Pouch of Douglas, uterosacral ligaments, etc.) or from adhesions pulling on the bowel (Aragon & Lessey, 2017; Ek et al., 2015). The incidence of endometriosis on the bowel itself ranges from 5% to 12% of those with endometriosis (Habib et al., 2020).

When endometriosis does involve the bowel, it most often found on the sigmoid colon, “followed by the rectum, ileum, appendix, and caecum” (Charatsi et al., 2018). “Extremely rare locations that have been reported include the gallbladder, the Meckel diverticulum, stomach, and endometriotic cysts of the pancreas and liver” (Charatsi et al., 2018). It can be difficult to determine bowel involvement from symptoms alone. Symptoms can range from none to crampy abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, pain with bowel movements, nausea, vomiting, and rarely rectal bleeding (Charatsi et al., 2018). Symptoms may be acyclical (all month long) and then aggravated during your period (Charatsi et al., 2018).

If your surgeon is suspicious of bowel involvement, they may do imaging prior to surgery to help guide care. Transvaginal ultrasounds and magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs) can be useful in detecting bowel involvement (but don’t necessarily rule it out) (Guerriero et al., 2018). According to one center that specializes in endometriosis surgery, “lesions on the colon, especially the distal sigmoid and rectum, I find ultrasound to be the most reliable” with the limitation that “it will only image the distal 20 cm of the colon, and lesions above that will be missed” (Pacific Endometriosis and Pelvic Surgery, n.d.). “For higher lesions on the sigmoid, the right colon, and small bowel then MRI is more accurate” (Pacific Endometriosis and Pelvic Surgery, n.d.).

Will surgery fix those IBS-like symptoms? It can be difficult to find studies that prove that. Mostly because “surgical techniques are not standardized” (Wolthuis et al., 2014). However, one center that specializes in endometriosis surgery found (with questionnaires of their patients) that their patients saw an “80% reduction in most bowel symptoms” (Center for Endometriosis Care, 2020). This rate may not be found with general gynecology surgery. If you think you might have bowel involvement, it is important to find the right care. The success of surgery depends on the skills and experience of the surgeon and a multidisciplinary team. It is recommended that “surgery should be performed by experienced surgeons, in centres with access to multidisciplinary care” (Habib et al., 2020, para. 1). While hormonal medications have been shown to help relieve symptoms, it may not stop the progression of the disease which can lead, in severe cases, to bowel obstruction; therefore, it is recommended that close follow-up be utilized if you do not choose surgical treatment (Habib et al., 2020; Ferrero et al., 2011).

- Interested in more info on bowel endo care from the experts? See the Endo Summit’s videos found on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QJRkk4-6cSk and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BXUllhdW2h0

- For more on surgical technique for bowel endometriosis look here.

- You can search for surgeons with skill on bowel endometriosis here.

- Problems with pelvic floor dysfunction and other issues can also contribute to some symptoms- see Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

References

Aragon, M., & Lessey, B. A. (2017). Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Endometriosis: Twins in Disguise. GHS Proc, 43-50. Retrieved from https://hsc.ghs.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/GHS-Proc-Ibs-And-Endometriosis.pdf

Center for Endometriosis Care. (2020). Bowel endometriosis. Retrieved from https://centerforendo.com/endometriosis-and-bowel-symptoms

Charatsi, D., Koukoura, O., Ntavela, I. G., Chintziou, F., Gkorila, G., Tsagkoulis, M., … & Daponte, A. (2018). Gastrointestinal and urinary tract endometriosis: a review on the commonest locations of extrapelvic endometriosis. Advances in medicine, 2018. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3461209

Ek, M. (2019). Gastrointestinal symptoms in women with endometriosis. Aspects of comorbidity, autoimmunity and inflammatory mechanisms (Doctoral dissertation, Lund University).

Ek, M., Roth, B., Ekström, P., Valentin, L., Bengtsson, M., & Ohlsson, B. (2015). Gastrointestinal symptoms among endometriosis patients—A case-cohort study. BMC women’s health, 15(1), 59. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0213-2

Ferrero, S., Camerini, G., Maggiore, U. L. R., Venturini, P. L., Biscaldi, E., & Remorgida, V. (2011). Bowel endometriosis: Recent insights and unsolved problems. World journal of gastrointestinal surgery, 3(3), 31. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3069336/

Guerriero, S., Saba, L., Pascual, M. A., Ajossa, S., Rodriguez, I., Mais, V., & Alcazar, J. L. (2018). Transvaginal ultrasound vs magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing deep infiltrating endometriosis: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 51(5), 586-595. Retrieved from https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/uog.18961

Habib, N., Centini, G., Lazzeri, L., Amoruso, N., El Khoury, L., Zupi, E., & Afors, K. (2020). Bowel Endometriosis: Current Perspectives on Diagnosis and Treatment. International Journal of Women’s Health, 12, 35. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6996110/

Moore, J. S., Gibson, P. R., Perry, R. E., & Burgell, R. E. (2017). Endometriosis in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: specific symptomatic and demographic profile, and response to the low FODMAP diet. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 57(2), 201-205. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12594

Pacific Endometriosis and Pelvic Surgery. (n.d.) Bowel disease. Retrieved from https://pacificendometriosis.com/bowel-disease/?fbclid=IwAR1EVUZJHHVk7wvdGwTwJ6Mo8QICiY8ktRtCXIotvhQzKqvTqa0LSjEZs-k

Wolthuis, A. M., Meuleman, C., Tomassetti, C., D’Hooghe, T., van Overstraeten, A. D. B., & D’Hoore, A. (2014). Bowel endometriosis: colorectal surgeon’s perspective in a multidisciplinary surgical team. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG, 20(42), 15616. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15616

Mast cells and endometriosis

Endometriosis is an inflammatory disorder, and this inflammation can lead to increased pain, fatigue, and general feelings of unwellness. Mast cells are immune system cells that can stimulate inflammation (Graziottin, Skaper, & Fusco, 2014). Mast cells hold proinflammatory substances (such as histamine, cytokines, prostaglandins, and more), and, when activated, release these proinflammatory substances (Weller, n.d.). When responding to a threat to the body and for healing, this is a good thing. But when mast cells are activated in endometriosis, not so much.

Activated mast cells (the ones that have released all those proinflammatory substances) have been found in higher quantities in endometriosis lesions versus normal tissue (Hart, 2015; Indraccolo & Barbieri, 2010; Sugamata et al., 2005). Estrogen seems to stimulate mast cells to support the inflammatory process (Zhu et al., 2018). In fact, estrogen receptors are found on mast cells and the high local levels of estrogen from endometriotic lesions may activate the mast cells and lead to pain (Hart, 2015; Zhu et al., 2018). While many therapies for endometriosis involve lowering estrogen production by the feedback loop between the brain and the ovaries, it should be remembered that endometriosis lesions demonstrate production of estrogen themselves (and also show resistance to progesterone) (Delvoux et al., 2009). In fact, the level of estrogen in endometriosis lesions were related to pain symptoms in patients with endometriosis while blood levels of estrogen were not (Zhu et al., 2018).

In addition, nerve fibers in endometriosis lesions have been shown to “release neural peptides such as nerve growth factor and substance P” that in turn activate mast cells to release those proinflammatory substances “which contributes to the development of pain and hyperalgesia in patients with endometriosis” (Zhu & Zhang, 2013). Those granules released by mast cells can contribute to new blood vessel growth, more inflammation, and nerve growth, which can lead to pain (Graziottin, 2009). This persistent inflammation from endometriosis lesions “intensifies neurogenic inflammation and tissue damage” leading to “progressive functional and anatomic damage associated with prominent tissue scarring, exemplified by the natural history of endometriosis” and “up-regulation of nerve pain” (Graziottin, 2009).

So, mast cells are recruited to endometriosis lesions, respond to the higher local estrogen and other inflammatory conditions, release their proinflammatory substances which can lead to pain and scarring. This effect of mast cells is associated in other pain syndromes as well, such as interstitial cystitis, IBS, vulvodynia, complex regional pain syndrome, migraines, and fibromyalgia (Aich et al., 2015).

References

Aich, A., Afrin, L. B., & Gupta, K. (2015). Mast cell-mediated mechanisms of nociception. International journal of molecular sciences, 16(12), 29069-29092. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms161226151

Delvoux, B., Groothuis, P., D’Hooghe, T., Kyama, C., Dunselman, G., & Romano, A. (2009). Increased production of 17β-estradiol in endometriosis lesions is the result of impaired metabolism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 94(3), 876-883. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/94/3/876/2596530

Graziottin, A., Skaper, S. D., & Fusco, M. (2014). Mast cells in chronic inflammation, pelvic pain and depression in women. Gynecological Endocrinology, 30(7), 472-477. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/09513590.2014.911280

Graziottin, A. (2009). Mast cells and their role in sexual pain disorders. Female Sexual Pain Disorders, 176. Retrieved from https://www.fondazionegraziottin.org/ew/ew_articolo/1820%20-%20mast%20cells%20and%20SPD.pdf

Hart, D. A. (2015). Curbing inflammation in multiple sclerosis and endometriosis: should mast cells be targeted?. International journal of inflammation, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/iji/2015/452095/

Indraccolo, U., & Barbieri, F. (2010). Effect of palmitoylethanolamide–polydatin combination on chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: Preliminary observations. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 150(1), 76-79. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301211510000424

Sugamata, M., Ihara, T., & Uchiide, I. (2005). Increase of activated mast cells in human endometriosis. American journal of reproductive immunology, 53(3), 120-125. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00254.x

Weller, C. (n.d.). Mast cells. Retrieved from https://www.immunology.org/public-information/bitesized-immunology/cells/mast-cells

Zhu, T. H., Ding, S. J., Li, T. T., Zhu, L. B., Huang, X. F., & Zhang, X. M. (2018). Estrogen is an important mediator of mast cell activation in ovarian endometriomas. Reproduction, 155(1), 73-83. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0457

Zhu, L., & Zhang, X. (2013). Research advances on the role of mast cells in pelvic pain of endometriosis. Journal of Zhejiang University (Medical Science), 42(4), 461. DOI: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2013.04.015

Your Story Isn’t Over; Mental Health Awareness

May is mental health awareness month and a good time to shine a light on the affects that endometriosis has on our mental health. A significant number of people worldwide suffer from a mental health disorder. While mental health covers a wide spectrum of disorders, two of the most pervasive are anxiety and depression (NAMI, 2021). Both of these not only affect a large portion of the population in general, but also can be found in higher rates in those with chronic illnesses- especially those involving chronic pain (Li et al., 2018).

Endometriosis has been associated “a wide spectrum of different types of pain, ranging from severe dysmenorrhea to chronic pelvic and other comorbid pain conditions” and those with endometriosis have an “elevated likelihood of developing depression and anxiety disorders” (Li et al., 2018). Endometriosis greatly affects quality of life, relationships, stress, professional life, and many other factors that can play into depression and anxiety (Donatti et al., 2017; Lagana et al., 2017). While these factors can play into depression and anxiety, research has suggested that endometriosis leads to specific changes in the brain that are associated with pain, anxiety, and depression (Lima Filho et al., 2019). For example, in a study done on mice, researchers found that “endometriosis led to changes in expression of several genes in the brain regions associated with pain, anxiety, and depression” (Li et al., 2018). In addition, some studies have shown a shared genetic predisposition between depression and endometriosis (Adewuyi et al., 2021).

Our mental health is important. As chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis can affect our mental health, it is important to address the underlying cause (Van den Broeck et al., 2013). But we also need to seek care for our mental health in other ways as well. We can’t do it all alone and seeking help from a professional for our mental health is every bit as important as seeking help for a broken bone. Just as we do physical therapy to help our musculoskeletal system, counseling and cognitive behavioral therapy is like physical therapy for our mental well-being. Endometriosis impacts our relationships, our ability to work, our sense of self, and pretty much every aspect of our lives. Seeking help to cope is not a sign of weakness, but of strength. One of my favorite symbols for mental health is from The Semicolon Project. The semicolon is a sign that the sentence, the story, isn’t over yet. Know that you are not alone, and your story isn’t over yet.

National Suicide Prevention Hotline: 1-800-273-8255

References

Adewuyi, E. O., Mehta, D., Sapkota, Y., Auta, A., Yoshihara, K., Nyegaard, M., … & Nyholt, D. R. (2021). Genetic analysis of endometriosis and depression identifies shared loci and implicates causal links with gastric mucosa abnormality. Human Genetics, 140(3), 529-552. doi: 10.1007/s00439-020-02223-6

Donatti, L., Ramos, D. G., Andres, M. D. P., Passman, L. J., & Podgaec, S. (2017). Patients with endometriosis using positive coping strategies have less depression, stress and pelvic pain. Einstein (São Paulo), 15(1), 65-70. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5433310/

Laganà, A. S., La Rosa, V. L., Rapisarda, A. M. C., Valenti, G., Sapia, F., Chiofalo, B., … & Vitale, S. G. (2017). Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. International journal of women’s health, 9, 323. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5440042/

Li, T., Mamillapalli, R., Ding, S., Chang, H., Liu, Z. W., Gao, X. B., & Taylor, H. S. (2018). Endometriosis alters brain electrophysiology, gene expression and increases pain sensitization, anxiety, and depression in female mice. Biology of reproduction, 99(2), 349-359. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioy035

Lima Filho, P. W. L., Chaves Filho, A. J. M., Vieira, C. F. X., de Queiroz Oliveira, T., Soares, M. V. R., Jucá, P. M., … & das Chagas Medeiros, F. (2019). Peritoneal endometriosis induces time-related depressive-and anxiety-like alterations in female rats: involvement of hippocampal pro-oxidative and BDNF alterations. Metabolic brain disease, 34(3), 909-925. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-019-00397-1

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (2021). Mental health by the numbers. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/mhstats

Van den Broeck, U., Meuleman, C., Tomassetti, C., D’Hoore, A., Wolthuis, A., Van Cleynenbreugel, B., … & D’Hooghe, T. (2013). Effect of laparoscopic surgery for moderate and severe endometriosis on depression, relationship satisfaction and sexual functioning: comparison of patients with and without bowel resection. Human Reproduction, 28(9), 2389-2397. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det260

Endometriosis and Pregnancy

Endometriosis is often associated with infertility. Infertility does not mean you cannot get pregnant, but rather there is a delay in achieving pregnancy. It is technically defined as not achieving a “clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse” (World Health Organization, n.d.). An estimated 30–50% of women with endometriosis are reported to have difficulty with infertility (Macer & Taylor, 2012). In addition, endometriosis does not have to be an “advanced stage” for it to affect fertility (Bloski & Pierson, 2008).

“Current evidence indicates that suppressive medical treatment of endometriosis does not benefit fertility and should not be used for this indication alone. Surgery is probably efficacious for all stages of the disease.”

(Ozkan, Murk, & Arici, 2008)

With infertility being related to endometriosis, it is unbelievable that pregnancy might still be recommended as a treatment for endometriosis. While some may have a temporary relief of symptoms, others can experience an increase. In fact, some “imaging and histopathology studies of endometriotic lesions during pregnancy show that they may grow rapidly during pregnancy” (Leeners & Farquhar, 2019). Pregnancy will not treat or cure endometriosis. Research has stated that “women aiming for pregnancy on the background of endometriosis should not be told that pregnancy may be a strategy for managing symptoms and reducing progression of the disease” (Leeners et al., 2018). This is echoed again by Leeners and Farquhar (2019) who point out that “the decision to have children should not be influenced by any perceived benefit of improving endometriosis but should be made solely on the wish for parenthood.”

While the overall risk is still low, endometriosis has been associated with some difficulties during pregnancy. Zullo et al. (2017) looked at 24 studies involving almost 2 million women with endometriosis to consider the possible effects of endometriosis during pregnancy . They found that “women with endometriosis have a statistically significantly higher risk of preterm birth, miscarriage, placenta previa, small for gestational age infants, and cesarean delivery” compared to healthy controls (Zullo et al., 2017). Zullo et al. (2017) did not find any significant association with gestational hypertension and preeclampsia with endometriosis; however, adenomyosis has been found to have some correlation with pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia (Porpora et al., 2020). Adenomyosis has been found to result in a higher likelihood of preterm birth, small for gestational age, and pre-eclampsia (Razavi et al., 2019). Adenomyosis and endometriosis frequently coexist, so it can be hard to determine how much is one or the other causing these effects (Choi et al., 2017).

On a positive note, Porpora et al. (2020) noted that “no difference in fetal outcome was found” and concluded that “endometriosis does not seem to influence fetal well-being”. This was also found by Uccella et al. (2019), stating that “neonatal outcomes are unaffected by the presence of the disease”. Again, a normal pregnancy is still highly possible. For more information on this topic, see Pregnancy and Endometriosis.

References

Bloski, T., & Pierson, R. (2008). Endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain: unraveling the mystery behind this complex condition. Nursing for women’s health, 12(5), 382-395. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-486X.2008.00362.x

Choi, E. J., Cho, S. B., Lee, S. R., Lim, Y. M., Jeong, K., Moon, H. S., & Chung, H. (2017). Comorbidity of gynecological and non-gynecological diseases with adenomyosis and endometriosis. Obstetrics & gynecology science, 60(6), 579. Retrieved from https://synapse.koreamed.org/upload/SynapseData/PDFData/3021ogs/ogs-60-579.pdf

Leeners, B., Damaso, F., Ochsenbein-Kölble, N., & Farquhar, C. (2018). The effect of pregnancy on endometriosis—facts or fiction?. Human reproduction update, 24(3), 290-299. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmy004

Leeners, B., & Farquhar, C. M. (2019). Benefits of pregnancy on endometriosis: can we dispel the myths?. Fertility and sterility, 112(2), 226-227. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.06.002

Macer, M. L., & Taylor, H. S. (2012). Endometriosis and infertility: a review of the pathogenesis and treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics, 39(4), 535-549. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3538128/pdf/nihms422379.pdf

Ozkan, S., Murk, W., & Arici, A. (2008). Endometriosis and infertility: epidemiology and evidence‐based treatments. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1127(1), 92-100. DOI: 10.1196/annals.1434.007

Porpora, M. G., Tomao, F., Ticino, A., Piacenti, I., Scaramuzzino, S., Simonetti, S., … & Benedetti Panici, P. (2020). Endometriosis and pregnancy: a single institution experience. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(2), 401. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/2/401

Razavi, M., Maleki‐Hajiagha, A., Sepidarkish, M., Rouholamin, S., Almasi‐Hashiani, A., & Rezaeinejad, M. (2019). Systematic review and meta‐analysis of adverse pregnancy outcomes after uterine adenomyosis. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 145(2), 149-157. Retrieved from https://www.endometriozisdernegi.org/konu/dosyalar/pdf/makale_ozetleri/Mayis2019/makale17.pdf

Uccella, S., Manzoni, P., Cromi, A., Marconi, N., Gisone, B., Miraglia, A., … & Ghezzi, F. (2019). Pregnancy after endometriosis: maternal and neonatal outcomes according to the location of the disease. American journal of perinatology, 36(S 02), S91-S98. DOI: 10.1055/s-0039-1692130

World Health Organization. (n.d.).Infertility definitions and terminology. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research/areas-of-work/fertility-care/infertility-definitions-and-terminology

Zullo, F., Spagnolo, E., Saccone, G., Acunzo, M., Xodo, S., Ceccaroni, M., & Berghella, V. (2017). Endometriosis and obstetrics complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertility and sterility, 108(4), 667-672. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.019

How to Study a Research Study

We post a lot of links and references to research studies, but it can be difficult to interpret them. Even harder is determining how relevant those studies are. Here are a few things to consider as you look at research on endometriosis.

When you look at research studies, you first want to assess how strong of evidence it is presenting. One quick way to tell is by the type of study. The University of Alabama at Birmingham (2021) has a good list of the types of studies, going from strongest evidence to weakest. In short:

“The most scientific, rigorous study designs are randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis. These types of studies are thought to provide stronger levels of evidence because they reduce, but do not eliminate, potential biases and confounders.”

(University of Alabama at Birmingham, 2021)

Bias is any errors in design that might throw off the conclusions. Bias, whether intentional or unintentional, can occur in “data collection, data analysis, interpretation and publication which can cause false conclusions” (Simundic, 2013). Find out more about that here. Confounding factors are any variables not factored into the study that can muddle with the interpretation of the results- “they can suggest there is correlation when in fact there isn’t” (Statistics How To, n.d.). This is important when looking at the conclusions drawn. For instance, in last week’s newsletter about endometriomas, we noted that recurrence rates are hard to tell from studies because their definition of “recurrence” varies widely from study to study (was it pathology from surgery or recurrence of symptoms that might actually be from a related condition?). You also want to look how large the study was, did it include several different variables, was it limited to a specific group, how was the study funded and what ethical considerations are given, etc. One tool for helping to analyze such factors can be found here.

Most studies have a short summary at the beginning that can be helpful. For instance, let’s look at this study from Shigesi et al. (2019) found here. The title itself tells us it is a systematic review and meta-analysis: “The association between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. So, we’re starting off good.

The study then starts with the summary called an abstract- which tells us the background of the problem they want to study, how they performed the study, the outcomes they found, and a discussion on what those outcomes mean. In the background, they state that “an association between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases has been proposed”, so that is what they are studying. Then they detail how they are going to study it- what databases they are using to look for information, what they are going to include or exclude from their study, and the statistical analysis they will utilize. They next present the outcomes: “the studies quantified an association between endometriosis and several autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), autoimmune thyroid disorder, coeliac disease (CLD), multiple sclerosis (MS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and Addison’s disease”. But wait! There is a caveat they note- “the quality of the evidence was generally poor due to the high risk of bias in the majority of the chosen study designs and statistical analyses” and that “only 5 of the 26 studies could provide high-quality evidence”. Then they present their conclusions of how this information might be useful- “the observed associations between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases suggest that clinicians need to be aware of the potential coexistence of endometriosis and autoimmune diseases when either is diagnosed”. They end by giving suggestions for future research that might strengthen the body of evidence for this. In short, after looking deeper into the association, the evidence available is overall poor so more research is warranted.

This is by no means a comprehensive review of looking at research study but rather a brief intro. There are many available resources on the internet for looking more in depth about how to assess research and draw conclusions from it.

References

Shigesi, N., Kvaskoff, M., Kirtley, S., Feng, Q., Fang, H., Knight, J. C., … & Becker, C. M. (2019). The association between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human reproduction update, 25(4), 486-503. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/humupd/article/25/4/486/5518352?login=true

Simundic, A. M. (2013). Bias in research. Biochemia medica, 23(1), 12-15. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900086/

Statistics How To. (n.d.). Confounding Variable: Simple Definition and Example. Retrieved from https://www.statisticshowto.com/experimental-design/confounding-variable/

University of Alabama at Birmingham. (2021). Study Types- Definitions. Retrieved from https://guides.library.uab.edu/ebd/evidencestrength

The Aggravating Endometrioma

What are endometriomas anyway? Endometriosis is classified into three main types: superficial peritoneal endometriosis, deep infiltrating endometriosis, and endometriomas (see more about that here). Endometriomas are ovarian cysts lined by endometriotic tissue and can be filled with blood (why they are at times called “chocolate cysts”). Like the other types of endometriosis, no one knows for sure how they form. It has been theorized that endometriosis tissue on the surface of the ovary invades and forms a cyst like formation or they start as a functional ovarian cyst with gradual infiltration of endometriotic tissue. Endometriomas have been found in up to 44% of those with endometriosis and are associated with deep infiltrating endometriosis (Cranney, Condous, & Reid, 2017).

Endometriomas can be suspected with ultrasound or MRI, but as with other types of endometriosis, surgery is gold standard for diagnosis (Gałczyński et al., 2019). Endometrioma treatment can often be focused on the effect on fertility, so it is important to consider your goals when looking at treatment options. While medications are used to manage endometriomas, “endometriomas do not respond to medical therapy alone, thus usually surgical treatment is necessary” (Gałczyński et al., 2019). Many may be hesitant to perform surgery for fear of loss of healthy ovarian function and may put off surgery until the endometrioma reaches a certain size. However, Gałczyński et al. (2019) reports that treating “early-stage endometrioma provides less damage to the ovary by a less invasive surgical procedure which decreases the risk of iatrogenic premature ovarian failure” and that “long-term ovarian endometriosis leads to persistent inflammation” that can lead to loss of ovarian function. Skill of the surgeon is important in this aspect.

Gałczyński et al. (2019) reports that “the level of expertise in endometriotic surgery is inversely correlated with inadvertent removal of healthy ovarian tissue along with the endometrioma capsule”. There are multiple surgical techniques that can be used to treat endometriomas and there is no consensus on the best method, although ovarian cystectomy (removal of the ovarian cyst) is the preferred method based on studies (Pais et al., 2021). One recently published study cites “excisional surgery allows for pain resolution, a high rate of spontaneous pregnancies and a lower recurrence rate of ovarian cysts when compared to drainage and ablation techniques” (Angioni et al., 2021).

The aggravating thing about endometriomas is the likelihood of recurrence. It can hard to tell true recurrence rates from studies because “recurrence is variously defined in the literature as the relapse of pain, clinical or instrumental detection of an endometriotic lesion, repeat rise in CA 125 levels, or evidence of recurrence found during repeat surgery,” which results in the wide range of reported recurrence in studies (Ceccaroni et al., 2019). In addition, the method of surgical treatment has a bearing on recurrence rate (excision versus draining etc.). One study reported recurrence rates to be “24.2% for patients aged 20–30 years, 17.7% for 31–40 years, and 7.9% for 41–45 years” (Li et al., 2019). Other studies have echoed that younger age was linked to increased recurrence (Gałczyński et al., 2019). While younger age seems to have a direct correlation with recurrence, other factors not as much. For instance, Gałczyński et al. (2019) reports that the “diameter of the tumor, stage of endometriosis, coexistence of deep-infiltrating endometriosis, or uni- or bi-lateral involvement of ovaries were all not associated with the risk of recurrence” and that the “median time to recurrence was 53 months”.

There is also controversy about the use of hormonal suppression to prevent recurrence. Some studies and a meta-analysis report that there is not enough evidence for the use of medications to help prevent recurrence, while others indicate that it may delay but will not prevent recurrence (Gałczyński et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Wattanayingcharoenchai et al., 2021). Confusing? Others agree that it is- with one commentary stating that “so what are we to believe and what should we advise women affected by endometriosis to do?” (Saridogan, 2020). In the end, we each have to do our research, look at our individual goals, and decide what is best for our unique situation.

Endometriosis after a hysterectomy or menopause

References

Angioni, S., Scicchitano, F., Sigilli, M., Succu, A. G., Saponara, S., & D’Alterio, M. N. (2021). Impact of Endometrioma Surgery on Ovarian Reserve. In Endometriosis Pathogenesis, Clinical Impact and Management (pp. 73-81). Springer, Cham. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-57866-4_8

Ceccaroni, M., Bounous, V. E., Clarizia, R., Mautone, D., & Mabrouk, M. (2019). Recurrent endometriosis: a battle against an unknown enemy. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 24(6), 464-474. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13625187.2019.1662391

Cranney, R., Condous, G., & Reid, S. (2017). An update on the diagnosis, surgical management, and fertility outcomes for women with endometrioma. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 96(6), 633-643. Retrieved from https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/aogs.13114

Gałczyński, K., Jóźwik, M., Lewkowicz, D., Semczuk-Sikora, A., & Semczuk, A. (2019). Ovarian endometrioma–a possible finding in adolescent girls and young women: a mini-review. Journal of ovarian research, 12(1), 1-8. Retrieved from https://ovarianresearch.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13048-019-0582-5

Li, X. Y., Chao, X. P., Leng, J. H., Zhang, W., Zhang, J. J., Dai, Y., … & Wu, Y. S. (2019). Risk factors for postoperative recurrence of ovarian endometriosis: long-term follow-up of 358 women. Journal of ovarian research, 12(1), 1-10. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13048-019-0552-y

Pais, A. S., Flagothier, C., Tebache, L., Almeida Santos, T., & Nisolle, M. (2021). Impact of Surgical Management of Endometrioma on AMH Levels and Pregnancy Rates: A Review of Recent Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(3), 414. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/10/3/414

Saridogan, E. (2020). Postoperative medical therapies for the prevention of endometrioma recurrence–do we now have the final answer?(Mini-commentary on BJOG-19-1705. R2). Authorea Preprints. Retrieved from https://d197for5662m48.cloudfront.net/documents/publicationstatus/41937/preprint_pdf/d4903f81caf3e8838e672d7631e6b8bd.pdf

Wattanayingcharoenchai, R., Rattanasiri, S., Charakorn, C., Attia, J., & Thakkinstian, A. (2021). Postoperative hormonal treatment for prevention of endometrioma recurrence after ovarian cystectomy: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 128(1), 25-35. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32558987/

Keep Endometriosis Awareness Going

As we come to the end of endometriosis awareness month, those of us with endometriosis knows it doesn’t end in March. Raising awareness and fighting against misinformation is a constant effort. Please feel free to share links from the webpage. The more we share, the more awareness and up-to-date information is out there for others. It can be discouraging to see so much of the same old misinformation perpetuated that can cause others to suffer as we have. Let’s spread hope!

We have collected all the infographs shared on Nancy’s Nook Facebook page and have sprinkled them throughout the website so that you can share the infograph and the link to more information. All the infographs are also collected here.

Endometriosis Quick Facts to Share is also another good resource to share. One of my favorites to reference to is the Myths and Misinformation page. Keep the awareness going, because endometriosis doesn’t stop in March.

The Personal Burden of Endometriosis

Last week we looked at the direct financial burden of endometriosis, including the loss of education, loss of productivity at work and home, and loss of income. Today we look at the personal burden of endometriosis- the altered relationships with family and friends, the pain and suffering, the ill effects on mental health, and the loss of who we feel we are as a person because of it.

Pain and fatigue can limit our ability to function and the quality of our life experience (Missmer et al., 2021). Our ability to maintain relationships can be difficult, especially when others do not understand the impact that endometriosis has on us. Much research has shown the effect on intimate partner relationships due to the interference with sexual health (Missmer et al., 2021). Not as many studies have been done on the effects of parenting with endometriosis; however, in our Facebook group Nancy’s Nook, many of you have shared the significant effect endometriosis has had on the ability to function as a parent. These limitations imposed from our illness can affect our mental health as well.

In studies, people with endometriosis express “feelings of worthlessness, guilt, and frustration connected with disease-related limitations on participation in daily activities, social functioning, independence, and interpersonal relationships” as well as frustration “from a woman’s inability to manage or predict her pain and the feeling that endometriosis/endometriosis-associated pain controls her life” (Missmer et al., 2021). Add to this the burden of the “perception that others (even healthcare professionals) consider what they are experiencing to be ‘all in their heads’” (Missmer et al., 2021). The struggle is real. And it is no wonder that many feel a loss of who they are as a person because of it.

On a positive note, a systematic review and meta-analysis, as well as other studies, reveal that surgery for endometriosis does improve quality of life (Arcoverde et al., 2019; Parra et al., 2021). Another study reports that “laparoscopic surgery is associated with improved quality of life and emotional well-being compared to medical therapies” and cautions that “although the GnRH agonists are effective in reducing endometriosis symptoms, they are often associated with anxiety and depression during treatment” (Laganà et al., 2017). To help manage symptoms, one study that surveyed people with endometriosis found that “heat (70%), rest (68%), and meditation or breathing exercises (47%)” helped and to a lesser degree “yoga/Pilates, stretching, and exercise” (Armour et al., 2019). Changes in diet, individualized to your specific needs, can help with symptom management for some (Karlsson, Patel, & Premberg, 2020). Other things such as acupuncture have been helpful to some as well. Mental healthcare is important to our well-being and should not be neglected either.

The impact endometriosis has on our lives is significant. Know that you are not alone.

References

Arcoverde, F. V. L., de Paula Andres, M., Borrelli, G. M., de Almeida Barbosa, P., Abrão, M. S., & Kho, R. M. (2019). Surgery for endometriosis improves major domains of quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology, 26(2), 266-278. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2018.09.774

Armour, M., Sinclair, J., Chalmers, K. J., & Smith, C. A. (2019). Self-management strategies amongst Australian women with endometriosis: a national online survey. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 19(1), 1-8. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12906-019-2431-x

Karlsson, J. V., Patel, H., & Premberg, A. (2020). Experiences of health after dietary changes in endometriosis: a qualitative interview study. BMJ open, 10(2), e032321. Retrieved from https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/2/e032321.abstract

Laganà, A. S., La Rosa, V. L., Rapisarda, A. M. C., Valenti, G., Sapia, F., Chiofalo, B., … & Vitale, S. G. (2017). Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. International journal of women’s health, 9, 323. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5440042/

Missmer, S. A., Tu, F. F., Agarwal, S. K., Chapron, C., Soliman, A. M., Chiuve, S., … & As-Sanie, S. (2021). Impact of Endometriosis on Life-Course Potential: A Narrative Review. International Journal of General Medicine, 14, 9. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S261139

Parra, R. S., Feitosa, M. R., Camargo, H. P. D., Valério, F. P., Zanardi, J. V. C., Rocha, J. J. R. D., & Féres, O. (2021). The impact of laparoscopic surgery on the symptoms and wellbeing of patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis and bowel involvement. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 42(1), 75-80. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2020.1773785

The Costly Burden of Endometriosis

Endometriosis has a powerful cost in terms of quality of life. However, there are financial costs as well. Financial loss can come from direct healthcare costs as well as loss of productivity. The estimated annual cost between those two in 2009 was $69.4 billion (Della Corte et al., 2020).

Della Corte et al. (2020) notes that “in employed women with endometriosis, as a consequence of productivity loss of 6.3 h per week, the total loss per person is approximately $10,177.54 per year.” Chronic pain is a significant factor in the loss of productivity and Armour et al. (2019) concludes that “priority should be given to improving pain control in women with pelvic pain.” Similarly, Facchin et al. (2019) notes that those with greater severity of symptoms were less likely to be employed and state that “endometriosis symptoms may significantly affect women’s professional life, with important socioeconomic, legal, and political implications.” The loss of productivity doesn’t only affect the workplace. Soliman et al. (2017) found that there was loss of household productivity as well.

The loss of productivity can start with symptom onset, starting in adolescence. Missmer et al. (2021) state that “endometriosis (and its associated symptoms) has been shown to hamper educational attainment, hinder work productivity, alter career choices and success, impair social life and activities, affect family choices, induce strain in personal relationships, negatively influence mental and emotional health, and adversely affect [quality of life]. These multiple and pervasive effects are anticipated to materially alter the life-course trajectory of women with endometriosis.”

So how can we help this? Earlier diagnosis and successful treatment are key. Surrey et al. (2020) notes that “patients with endometriosis who had longer diagnostic delays had more pre-diagnosis endometriosis-related symptoms and higher pre-diagnosis healthcare utilization and costs compared with patients who were diagnosed earlier after symptom onset, providing evidence in support of earlier diagnosis.” On the same note, Missmer et al. (2021) state that “unfortunately, current practice models too often result in a prolonged delay between symptom onset, diagnosis, and treatment of endometriosis, thereby increasing the impact on the life course.” This is why we advocate and share evidence-based information- so that the next person doesn’t have their life so significantly altered by endometriosis.

References

Armour, M., Lawson, K., Wood, A., Smith, C. A., & Abbott, J. (2019). The cost of illness and economic burden of endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain in Australia: A national online survey. PloS one, 14(10), e0223316. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0223316

Della Corte, L., Di Filippo, C., Gabrielli, O., Reppuccia, S., La Rosa, V. L., Ragusa, R., … & Giampaolino, P. (2020). The burden of endometriosis on women’s lifespan: a narrative overview on quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4683. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/13/4683/htm

Facchin, F., Buggio, L., Ottolini, F., Barbara, G., Saita, E., & Vercellini, P. (2019). Preliminary insights on the relation between endometriosis, pelvic pain, and employment. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation, 84(2), 190-195. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1159/000494254

Missmer, S. A., Tu, F. F., Agarwal, S. K., Chapron, C., Soliman, A. M., Chiuve, S., … & As-Sanie, S. (2021). Impact of Endometriosis on Life-Course Potential: A Narrative Review. International Journal of General Medicine, 14, 9. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S261139

Soliman, A. M., Coyne, K. S., Gries, K. S., Castelli-Haley, J., Snabes, M. C., & Surrey, E. S. (2017). The effect of endometriosis symptoms on absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace and at home. Journal of managed care & specialty pharmacy, 23(7), 745-754. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.7.745

Surrey, E., Soliman, A. M., Trenz, H., Blauer-Peterson, C., & Sluis, A. (2020). Impact of endometriosis diagnostic delays on healthcare resource utilization and costs. Advances in therapy, 37(3), 1087-1099. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12325-019-01215-x