Anti-Mullerian Hormone & Endometriosis – What’s The Connection?

Endometriosis has been associated with a marker called Antimullerian hormone (AMH), which is a pivotal marker of ovarian reserve, and is commonly measured in women with endometriosis specifically in relation to fertility. There is debate among the community that your AMH level is what it is and it cannot change. I would challenge this notion though as I have seen people with endometriosis have significant increases after proper excision surgery, which is a point of debate. Recently, I had another patient send me lab work that demonstrated what some may call a low AMH, has confirmed endometriosis, but likely a surgery that was incomplete and is continuing to suffer ongoing symptoms. Though I have seen this change in my patients, I recognize this is only a small fraction of the people suffering, so it was time to review what the research says. This article aims to provide a review of the various studies conducted on this critical subject, exploring how endometriosis and AMH interact, the effect of surgical intervention on AMH levels, and the subsequent impact on fertility.

Table of contents

The Antimullerian Hormone (AMH): A Brief Overview

AMH, a hormone playing diverse roles during embryonic development and puberty, is produced by ovarian follicles smaller than 8 mm, hence linking ovarian reserve to AMH levels in the blood. The normal range for AMH hovers between 1 and 4 ng/mL. However, women’s AMH levels greatly vary based on factors like age, ethnic background, lifestyle, and genetics. Additionally, someone at the low end of range may still suffer problems despite them being “in range.”

AMH Testing in Reproductive Health

AMH testing is a crucial tool for evaluating female fertility. It can assist in:

- Assisting with understanding the prognosis of a woman’s response to assisted reproduction techniques (ART) such as in vitro fertilization (IVF)

- Confirming other markers of menopause

- Providing a more comprehensive evaluation when certain conditions are confirmed or suspected such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), premature ovarian failure, and endometriosis

Endometriosis and AMH Levels

Endometriosis is a common culprit behind infertility, affecting nearly half of the women suffering from this ailment. This infertility arises from various factors, including inflammation in the reproductive tract, scar tissue-induced decreased blood supply to the ovaries, and pelvic anatomical distortions. Research reveals a significant correlation between endometriosis and lower than average AMH levels.

Some argue that surgical intervention of endometriosis often leads to a reduction in AMH levels, though many of us in the community may argue that this is a more nuanced topic and this highly depends on the skill of the surgeon, something that is often overlooked in endometriosis research. Various studies have attempted to decipher the impact of endometriosis surgery on AMH levels and fertility outcomes. A retrospective study conducted in 2016 found that preoperative AMH levels did not influence pregnancy rates after surgery. This is consistent with the literature we have on surgical impact, and thus the need for better research in the future. In my experience, this is the opposite of what I have seen, as many of us have seen when people get to the right surgeon.

Laparoscopic Cystectomy on AMH Levels

Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy, a common surgical procedure to treat endometriomas, has been associated with decreased ovarian reserve. A study in 2019 demonstrated significantly lower AMH levels in women who underwent laparoscopic endometrioma cystectomy, especially in cases with bilateral cysts larger than 7 cm and stage 4 endometriosis.

Considerations: I want to highlight that we do not know the skill of the surgeon, but we do know that the skill of the surgeon matters. That being said, large endometriomas can often overtake ovarian tissue which is what happened to Christina. Hear her story here. This is why it is extremely important to find a knowledgeable surgeon that you feel comfortable with. If you need help finding a surgeon, you can start here.

Laparoscopic Endometriosis Surgery on AMH Levels

A literature review and meta-analysis of 19 studies conducted between 2010 and 2019 on the impact of laparoscopic endometriosis surgery on AMH levels post-surgery revealed a decline in AMH levels, extending beyond six months post-surgery. This decline was more pronounced in cases where surgery was performed on both sides of the body, compared to a single side.

Again, I would argue that we consider the quality of the research and the skill of the surgeon. Remember, ablation is different from excision and this may be another factor that is skewing results. I repeat this because, like many of us in the community, this is not our experience, thus I often read research with these things in mind. If many others in the community are also seeing this, there must be more to consider than what is presented. The bottom line is that we need better research.

AMH Levels Post-Surgery for Endometrioma

Several studies have observed that laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy results in a significant and progressive decrease in AMH levels post-surgery. However, other studies have noted that this decrease may only be temporary, with levels potentially returning to normal within a year. Another factor to consider is when the AMH was measured post-surgery and what other factors may have impacted the levels!

Certain studies have observed a temporary decrease in AMH levels following endometrioma ablation. However, this decrease did not persist beyond six months in most cases, suggesting a potential recovery of ovarian reserves.

Several studies have compared the decrease in AMH levels following ovarian cystectomy and endometrioma vaporization. The general consensus suggests a higher postoperative decline in AMH levels following cystectomy compared to vaporization, particularly in bilateral endometrioma cases.

This caught my attention and highlights my thoughts on how the surgery (excision) is being performed as to not compromise ovarian tissue. Using ablation, which is what the CO2 laser is referring to, may not compromise the ovarian tissue, but it also may not treat the disease. Paul Tyan, MD discusses this complex topic in our interview which you can find here.

The combined technique, involving partial cystectomy and ablation, has been shown to have less detrimental effects on the ovary, resulting in a lesser decline in AMH levels post-surgery.

The role of endometriosis surgery in improving pregnancy rates remains a topic of debate. Some studies suggest that surgery might improve the success rates of fertility treatment, while others highlight the risk of ovarian damage due to surgical intervention.

In conclusion, the Antimullerian hormone is a vital marker for assessing the impact of endometriosis and its surgical intervention on ovarian reserve and fertility. Understanding the complex relationship between AMH levels, endometriosis, and surgical intervention along with identifying gaps in the research can help medical professionals devise more effective treatment strategies, improve the quality of research studies which ultimately improves patient outcomes.

IRelated Reading:

- Does Endometriosis Cause Infertility? Covering the Basics

- Endometriosis and Pregnancy: Natural, Medical, & Surgical Options

References:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6603105/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7865255/

- https://drseckin.com/endometriosis-surgery-and-amh-levels/

Endometriosis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Distinguishing the Differences

Exploring the complex world of health and medical conditions can sometimes feel like navigating through a labyrinth. The similarities between certain conditions often blur the lines, making it challenging for individuals and even healthcare professionals to differentiate between them. This is notably true in the case of endometriosis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), two disorders that share several overlapping symptoms and characteristics. We’ve recently been discussing endometriosis and the bowel, this article aims to shed light on these conditions, highlighting the differences, similarities, and the challenges faced in their diagnosis.

Table of contents

Symptoms of Endometriosis

The signs and symptoms of endometriosis can vary greatly, making it a complex disease to diagnose. Some of the most common symptoms include dysmenorrhea (painful periods), dyspareunia (painful intercourse), chronic pelvic pain, and gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal pain. Because endometriosis symptoms often overlap with GI symptoms, getting a diagnosis in general can be tricky, but especially if it may be impacting the bowels which is estimated in about 5-12% of cases, whereas approximately 90% of those with endometriosis suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms. In many cases, these symptoms can be mistaken for other conditions, leading to delays in diagnosis.

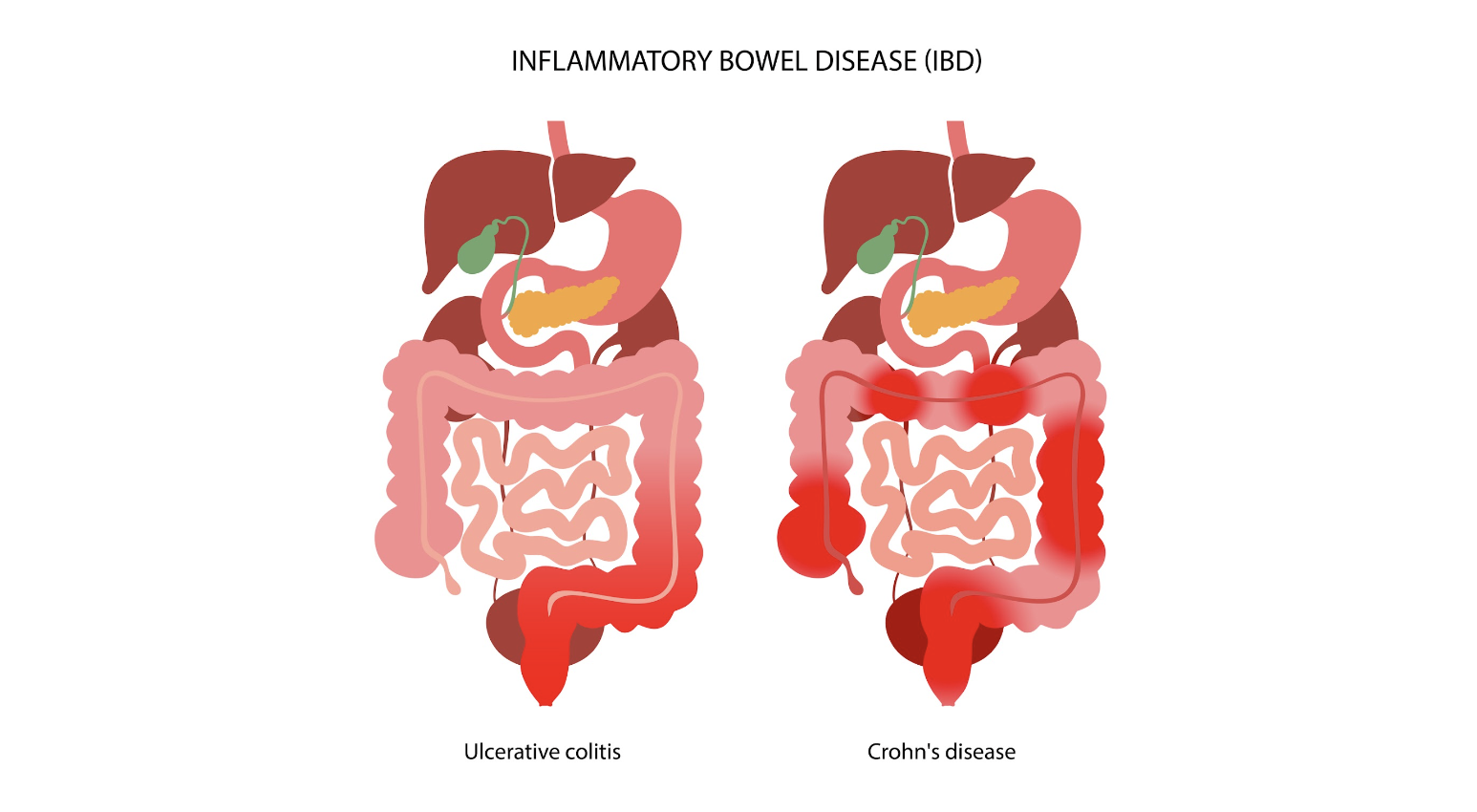

Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Overview

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an umbrella term that encompasses two chronic autoimmune disorders: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). These conditions are characterized by the chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, which can lead to a wide range of symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue.

The prevalence of IBD is highest in Europe, with reported cases reaching up to 505 per 100,000 for UC in Norway and 322 per 100,000 for CD in Italy. Like endometriosis, IBD can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life, necessitating long-term management strategies to control symptoms and prevent complications.

The Overlap: Endometriosis and IBD

Interestingly, endometriosis and IBD share several common traits, including immune dysregulation and overlapping clinical manifestations like abdominal pain and bowel-related symptoms. This overlap often poses a significant diagnostic challenge, as endometriosis can mimic IBD or vice versa, leading to delays or indeterminate diagnosis.

In fact, endometriosis has often been termed as having “IBD-like” features due to the similarities in symptoms and underlying pathophysiology. This has led to substantial interest in the potential link between these conditions, with several studies investigating the co-occurrence of endometriosis and IBD.

Investigating the Link: Endometriosis and IBD

To understand the potential link between endometriosis and IBD, numerous studies have been conducted, ranging from case reports and clinical series to epidemiological research. These studies have reported varying results, further highlighting the complexity of these conditions and the challenges associated with their diagnosis and management.

Case Reports and Clinical Series

Many case reports have been published that highlight the diagnostic challenges associated with endometriosis and IBD. For instance, several cases have been reported where an initial diagnosis of CD was later revised to intestinal endometriosis upon histopathological examination. Similarly, other case reports have documented instances where an initial diagnosis of UC was later confirmed to be appendiceal endometriosis.

Conversely, there have also been cases where an initial diagnosis of endometriosis was later revised to be CD upon histopathological examination. Additionally, several case reports have documented instances where both CD and endometriosis were diagnosed in the same patient.

Epidemiological Studies

In addition to case reports and clinical series, several epidemiological studies have investigated the co-occurrence of endometriosis and IBD. One such study, a nationwide Danish cohort study, reported a 50% increase in the risk of IBD in women with endometriosis compared to the general population. This increased risk persisted even more than 20 years after a diagnosis of endometriosis, suggesting a genuine association between the two conditions..

Another study, a retrospective cross-sectional study conducted in Israel, found that 2.5% of patients with endometriosis also had a diagnosis of IBD, compared to 1% in the general population. A recent Italian case-control study found that among 148 women with endometriosis, five had IBD, although this did not reach statistical significance.

The Challenge of Temporality

One of the critical aspects of evaluating the association between endometriosis and IBD is the issue of temporality, or the order in which the conditions are diagnosed. Many studies do not provide information on the temporal sequence of endometriosis and IBD, which poses a significant challenge in determining a cause-effect relationship between the two conditions.

Furthermore, the diagnosis of endometriosis often faces delays, with an average delay of seven years estimated between the onset of symptoms and definitive diagnosis. This delay further complicates the evaluation of the temporal relationship between endometriosis and IBD.

Distinguishing Between Endometriosis and IBD

Given the overlapping symptoms and shared characteristics of endometriosis and IBD, distinguishing between these conditions can be challenging. Both conditions can result in similar symptoms, such as abdominal pain and bowel-related symptoms, which can lead to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

In cases where endometriosis and IBD coexist, the symptoms can be atypical and cyclic, and fibrosis caused by chronic inflammation can lead to obstruction of the intestinal lumen. Therefore, it’s essential for healthcare professionals to consider both conditions when evaluating patients with such symptoms.

In cases of intestinal endometriosis, endoscopic biopsies may reveal IBD-like lesions. However, these lesions may represent an epiphenomenon of endometriosis rather than a true IBD. Hence, patients with concurrent IBD and endometriosis should be adequately followed up for the reassessment of IBD diagnosis over time.

The Role of Treatment in the Risk of IBD

The treatment of endometriosis could potentially influence the risk of developing IBD. For instance, oral contraceptives are a common treatment for endometriosis, and a meta-analysis of 14 studies suggested an increased risk of IBD among users of oral contraceptives. Additionally, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), often used for pain relief in endometriosis, have been reported to increase the risk of IBD.

The Need for Further Research

Though existing research has shed some light on the association between endometriosis and IBD, there is still much to uncover. Further research is needed to better understand the temporal relationship between endometriosis and IBD in cases of co-occurrence and identify predictors that could be useful for evaluation and management of these patients.

Understanding these conditions and their potential links can not only improve diagnostic accuracy but also inform treatment strategies and improve the quality of life for those affected.

Distinguishing between endometriosis and inflammatory bowel disease can be a challenging task due to the overlapping symptoms and shared characteristics of these conditions. However, understanding the nuances of these conditions and the potential links between them can lead to improved diagnostic accuracy and more effective treatment strategies. As research progresses in this area, we hope to gain a better understanding of these complex conditions and continue to improve the lives of those affected.

Related Reading:

- Finding an Endometriosis Specialist: Your Guide to Effective Treatment

- Unraveling the Connection Between Endometriosis and Autoimmune Diseases

References:

- Parazzini F, Luchini L, Vezzoli F, Mezzanotte C, Vercellini P. Gruppo italiano perlo studio dell’endometriosi. Prevalence and anatomical distribution of endometriosisin women with selected gynaecological conditions: results from amulticentric Italian study. Hum Reprod 1994;9:1158–62.

- Bulun SE. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2009;360:268–79.

- Weed JC, Ray JE. Endometriosis of the bowel. Obstet Gynecol 1987;69:727–30.

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54.

- Nielsen NM, Jorgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Rostgaard K, Frisch M. The co-occurrence of endometriosis with multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren syndrome. Hum Reprod 2011;26:1555–9.

Rediscovering Life After Endometriosis Surgery: Tips and Strategies for a Full Recovery

Endometriosis surgery, typically excision of endo implants and related fibrosis, using minimally invasive laparoscopy or robotic surgery, significantly impacts women’s health and recovery journey. Here’s an enhanced guide to life post-surgery, incorporating tips to improve physical and mental healing towards lasting thrivorship.

Table of contents

Understanding Endometriosis and Its Surgical Treatment

Endometriosis involves the growth of tissue similar to the uterine lining outside the uterus, creating pain and sub-fertility. Thankfully, minimally invasive surgery requires only small incisions through which a camera and instruments can be placed. This is the gold standard for diagnosing and treating endometriosis and has revolutionized the healing process and length of time to full recovery. (Ferrero et al., 2018).

The Recovery Period

Recovery from laparoscopic or robotic minimally invasive surgery varies based on the extent of endometriosis and overall health. Typically, full recovery involves several weeks to a few months. Patients might experience tiredness initially and are advised to consume soft foods, stay hydrated, and take fiber supplements to avoid constipation, especially when using narcotic pain relief. It’s crucial to initially avoid strenuous activities but engage in light walks to promote healing. This reduces the risk of venous clots in the legs but avoids complications like hernias through the incisions.

How long you should take off work depends on the extent of the surgery, physical job demands, and any known medical co-existing conditions that might slow the healing process, such as diabetes. Discuss this with your surgeon before the procedure to set realistic expectations.

Enhanced Recovery Tips

- Balanced Nutrition: Within limits of allergies and food intolerance which may be specific to you, the following is a generic prudent healing plan:

- Protein: Lean meats, fish, eggs, tofu, and legumes help repair tissues.

- Fruits and Vegetables: Rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants to reduce inflammation.

- Whole Grains: Brown rice, quinoa, and whole wheat bread for energy and fiber.

- Healthy Fats: Avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil for inflammation control.

- Hydration: Plenty of water, green and herbal teas.

- Bromelain Supplements: Bromelain, an enzyme found in pineapples, can reduce inflammation and promote healing by minimizing post-surgical scarring (Walker et al., 2018).

- Arnica: Homeopathic arnica can help reduce bruising and swelling, and may reduce pain as well.

- Vitamin C and Zinc: Essential for tissue repair and immune function.

- Probiotics: Support gut health, which can be disrupted by surgery, antibiotics used around the time of surgery, and pain medications.

- Red Light Therapy: Otherwise known as photobiomodulation, this modality can exert and anti-inflammatory effect, reducing prolonged inflammation and thereby can promote healing. Keep in mind, acute inflammation is part of normal healthy healing, so it may be prudent to avoid this for at least a month postop. (Hamblin MR)

Physical Health Post-Surgery

Post-surgery, physical health generally improves, with reduced bodily pain and better physical functioning. However, side effects like hot flashes can occur, particularly if the ovaries are removed or compromised and/or hormonal treatments are part of the post-surgery plan. Regular follow-ups are essential to monitor recovery and address any complications promptly. This is a highly individualized situation, so work with an expert before and after surgery.

Pain Management

- Heat Therapy: Use heating pads to alleviate abdominal pain. Be careful not to burn skin by not using something like a towel between the heat source and the skin.

- TENS Units: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation can help manage pain by sending small electrical pulses to the affected areas.

- Acupuncture: Can relieve pain and promote healing.

Mental Health Post-Surgery

Mental health is a crucial aspect of recovery. Enduring a chronic condition like endometriosis can lead to anxiety and depression. Therefore, incorporating mental health support into post-surgery care can be vital. Many women report improved emotional well-being post-surgery, but not all. So ongoing support may be necessary to manage any lingering psychological effects (Stratton et al., 2020).

Mental Health Tips

- Therapy and Counseling: Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can be effective.

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Practices like yoga and meditation can help manage stress and improve mental clarity.

- Support Groups: Joining endometriosis support groups can provide emotional support and practical advice.

Fertility and Family Planning

Fertility and family planning are significant concerns for many women with endometriosis. Studies show that surgery could double the spontaneous pregnancy rate in people with mild endometriosis. Those with moderate to severe endometriosis also have improved spontaneous birth rates after the laparoscopic removal of endometrial-like lesions.

However, even after successful surgery, some women may struggle with fertility issues. It is essential to have a candid discussion about fertility and family planning with your healthcare provider before surgery.

Financial Considerations

Endometriosis surgery can be financially burdensome. Many specialists are out-of-network, leading to high out-of-pocket costs in many, but not all, cases. It’s best to discuss potential expenses with your insurance provider and surgeon’s office beforehand. Additionally, explore options like payment plans or grants for financial support.

Managing Recurrence

Despite effective surgery, endometriosis can recur. Studies indicate a 51% recurrence rate within ten years. However, it can be in the 5-10% range if complete excision of visible implants is possible. This may require additional interventions that are often hormonally based but can also be integrative and holistic to some degree. Risk factors for recurrence include age, ovarian endometriosis, incomplete removal of lesions, and the initial surgeon’s expertise. Regular monitoring and follow-up surgeries may be required to manage recurrences effectively. It is very prudent to find the most experienced and highly trained surgeon possible. Here is a review of what you should be looking for in selecting a surgeon.

Prevention Strategies

- Hormonal Treatments: Birth control pills, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, and other hormonal therapies can help prevent recurrence but may also carry significant and prolonged side effects. In general, the least potentially harmful option should be considered first and this should be highly individualized with your endo expert and/or reproductive endocrinologist.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Maintaining a healthy diet, avoiding toxins and regular exercise can support overall health and reduce the risk of recurrence by modulating and more efficiently eliminate excess estrogen in your system.

- Anti-inflammatory Diet: Incorporate foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants to reduce inflammation. It is best to craft a personalized plan with a nutrition expert.

Holistic Approaches

- Herbal Supplements: Consider supplements like turmeric, which has anti-inflammatory properties.

- Aromatherapy: Essential oils like lavender and peppermint can aid in relaxation and pain relief.

Conclusion

Quality of life after endometriosis surgery involves a multifaceted approach to physical and mental health, fertility, and financial planning. By understanding the recovery process and incorporating comprehensive care strategies, women can optimally navigate their post-surgery journey. Work with an endometriosis expert.

References

- Ferrero S, Evangelisti G, Barra F. Current and Emerging Treatment Options for Endometriosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(11):1109-1125. doi:10.1080/14656566.2018.1507067. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30096049/

- Vercellini P, Buggio L, Frattaruolo MP, Borghi A, Dridi D, Somigliana E. Medical treatment of endometriosis-related pain. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:68-91. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.06.001. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30126775/

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1244-1256. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1810764. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32212520/

Updated Post: July 09, 2024

Colon Chronicles: Delving into Bowel Endometriosis

In our recent blog, we highlighted the significance of addressing bowel endometriosis, a condition prone to misdiagnosis. Whether individuals have struggled with lifelong bowel issues or are suddenly facing disruptions, determining what’s considered normal can be perplexing. The “normal” range spans anywhere from three times a day to as infrequent as three times per week. In many sources, the focus is typically limited to frequency and to some degree consistency; however, there’s an overall scarcity of information on what defines normalcy.

Table of contents

ICYMI: Understanding Bowel Endometriosis

This ambiguity is particularly challenging for those with endometriosis, where gastrointestinal symptoms vary widely, making it tough to discern what’s amiss. About 90% of endometriosis cases involve some form of gastrointestinal symptoms, often leading to an IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) diagnosis, which essentially offers a label for persistent symptoms without an identifiable cause. The usual next step in diagnostics is often a colonoscopy, a key tool for identifying or ruling out certain diseases. This article explores the nuances of bowel endometriosis, with a primary focus on the role and precision of colonoscopy in diagnosing this condition.

Bowel endometriosis is considered to be deep infiltrating endometriosis and can lead to a variety of symptoms which we discussed in the previous blog, but is often concerning if not diagnosed timely and may risk more complex surgeries including resection if the disease is not properly addressed.

Related Reading: How to Get an Endometriosis Diagnosis

The Role of Colonoscopy – Is it helpful?

A colonoscopy is a diagnostic procedure commonly used to examine the inner lining of the large intestine (colon and rectum). It involves the use of a long, flexible tube called a colonoscope, which has a small camera attached to its end. This tool allows physicians to visualize the interior of the colon to identify any abnormal conditions or changes.

In the context of bowel endometriosis, a colonoscopy can potentially detect signs of endometrial tissue growth within the bowel. However, its effectiveness and accuracy in diagnosing this condition have been subjects of ongoing research and debate. Aside from its ability to detect endometriosis, there is also consideration of the provider performing the procedure and their level of knowledge of endometriosis.

The use of colonoscopy in diagnosing bowel endometriosis has been a topic of considerable discussion among medical professionals. Given the invasive nature of the procedure and the often non-specific symptoms of bowel endometriosis, the role and necessity of colonoscopy in its diagnostic process have been questioned.

However, several case studies and research findings suggest that colonoscopy can indeed play a crucial role in identifying bowel endometriosis. In particular, it has been found to be effective in detecting endometriosis growth in the bowel, with certain colonoscopic findings such as eccentric wall thickening, polypoid lesions, and surface nodularities often being associated with endometriosis.

Evaluating the Accuracy of Colonoscopy for Diagnosing Bowel Endometriosis

While the potential of colonoscopy in detecting bowel endometriosis has been recognized, its accuracy in doing so has been the subject of extensive research. A number of studies have sought to evaluate the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of colonoscopy in diagnosing this condition.

One such study was conducted by Milone M et al., who performed a prospective observational study that included women diagnosed with deep pelvic endometriosis. The study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of colonoscopy in predicting intestinal involvement in deep pelvic endometriosis.

The results of the study suggested that colonoscopy did have the potential to detect bowel endometriosis, with a number of cases accurately diagnosed through the procedure. However, the overall sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of colonoscopy were found to be variable, indicating room for improvement in its diagnostic accuracy.

In another study conducted by Marco Milone and his team, the researchers also found that while colonoscopy could indeed identify bowel endometriosis, its accuracy was not optimal. The study elucidated that the presence of colonoscopic findings of intestinal endometriosis in deep pelvic endometriosis was quite low, indicating that routine colonoscopy may not be justified for all women with deep pelvic endometriosis.

A Case Study: Bowel Endometriosis and Colonoscopy

To illustrate the potential role of colonoscopy in diagnosing bowel endometriosis, let’s consider a case study involving a 45-year-old woman who presented with abdominal pain in her left lower quadrant. This woman underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a submucosal tumor-like lesion in her sigmoid colon.

Upon further examination using magnifying endoscopy, the lesion was found to contain sparsely distributed round pits – a finding that was suggestive of endometrial glands and stroma (the histological definition of endometriosis). This discovery led to a biopsy of the lesion, the results of which confirmed the presence of intestinal endometriosis.

This case study serves to highlight how colonoscopy, when combined with other diagnostic methods like magnifying endoscopy and biopsy, can aid in the detection and diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

The Future of Bowel Endometriosis Diagnosis

While the role and accuracy of colonoscopy in diagnosing bowel endometriosis have been explored, research in this area is ongoing. The development and refinement of diagnostic methods are crucial for improving the detection and treatment of bowel endometriosis.

In parallel with the innovations in medical technology, new diagnostic methods such as magnifying chromoendoscopy, target biopsy, and virtual colonoscopy are being explored and studied for their potential to improve the accuracy of bowel endometriosis diagnosis. These advancements, coupled with a deeper understanding of the condition, may pave the way for more accurate and less invasive diagnostic options in the future.

Bowel endometriosis is a complex condition that can significantly impact the quality of life of those affected. While colonoscopy can play a role in its diagnosis, its effectiveness and accuracy are subject to continuous research and improvement. Exploring new diagnostic methods and refining existing ones are crucial steps toward enhancing the detection and treatment of this condition. As we continue to learn more about bowel endometriosis and its nuances, we can hope for more efficient and accurate diagnostic tools in the future.

Related Reading:

- Endo-Fighting Microbiome Optimization: Research-based Tips

- Endometriosis and the Microbiome: Insights and Emerging Research

References:

- Walter SA, Kjellström L, Nyhlin H, Talley NJ, Agréus L. Assessment of normal bowel habits in the general adult population: the Popcol study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(5):556-566. doi:10.3109/00365520903551332

- Habib, N., Centini, G., Lazzeri, L., Amoruso, N., El Khoury, L., Zupi, E., & Afors, K. (2020). Bowel Endometriosis: Current Perspectives on Diagnosis and Treatment. Int J Womens Health, 12, 35-47. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S190326

- Milone, M., Mollo, A., Musella, M., Maietta, P., Sosa Fernandez, L. M., Shatalova, O., Conforti, A., Barone, G., De Placido, G., & Milone, F. (2015). Role of colonoscopy in the diagnostic work-up of bowel endometriosis. World J Gastroenterol, 21(16), 4997-5001. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4997

- Tomiguchi, J., Miyamoto, H., Ozono, K., Gushima, R., Shono, T., Naoe, H., Tanaka, M., Baba, H., Katabuchi, H., & Sasaki, Y. (2017). Preoperative Diagnosis of Intestinal Endometriosis by Magnifying Colonoscopy and Target Biopsy. Case Rep Gastroenterol, 11(2), 494-499. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475751

Understanding Bowel Endometriosis

Bowel Endometriosis is a debilitating chronic health condition that affects a significant number of women worldwide. This disease is characterized by the growth of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, specifically on or inside the bowel walls. The condition often presents with varying gastrointestinal symptoms like painful bowel movements, constipation, and diarrhea, making it difficult to diagnose.

Table of contents

What is Bowel Endometriosis?

Bowel Endometriosis is a specific form of endometriosis that involves the intestines. In this condition, cells similar to those that line the uterus start growing on the bowel or even penetrate into the bowel wall. This growth can lead to painful and uncomfortable symptoms, particularly during a woman’s menstrual cycle.

Prevalence and Affected Areas

Bowel Endometriosis is a subset of a larger condition, endometriosis, affecting 1 in 5 endo patients. The most common sites for bowel involvement are the rectum, appendix, sigmoid, cecum, and distal ileum. It’s also worth noting that bowel endometriosis frequently co-exists with endometriosis in other areas, making it a multifaceted disease that requires comprehensive treatment.

Symptoms of Bowel Endometriosis

Understanding the symptoms of bowel endometriosis can help in early diagnosis and treatment. It’s essential to note that these symptoms often overlap with other gastrointestinal conditions, making it a challenging disorder to diagnose.

Common Symptoms of Endometriosis

- Painful bowel movements: This is one of the most common symptoms of bowel endometriosis. The pain is often described as sharp or cramping and may worsen during menstruation.

- Constipation and Diarrhea: Changes in bowel habits are another common symptom. Some women may experience constipation, while others may have diarrhea. These symptoms may also worsen during menstruation.

- Rectal Bleeding: While not as common, some women may experience rectal bleeding, particularly during their menstrual period. A healthcare professional should always evaluate this symptom as it can also be a sign of other serious conditions.

- Abdominal Pain: Abdominal pain, often worsening during the menstrual cycle, is another common symptom. The pain can range from mild to severe and may be constant or intermittent.

- Dyspareunia: Dyspareunia, or painful sex, is another symptom that may indicate the presence of bowel endometriosis. This pain often stems from endometriosis lesions in the posterior pelvic compartment peritoneum, an area around the rectum that includes the surface peritoneum, commonly called the pouch of Douglas.

Diagnosing Bowel Endometriosis

Diagnosing bowel endometriosis can be challenging due to the overlap of symptoms with other gastrointestinal disorders. However, several diagnostic tools can aid in the identification of this condition.

Physical Examination and Patient History

A detailed patient history and a thorough physical examination are crucial first steps in diagnosing bowel endometriosis. The doctor will ask about the symptoms, their severity, and if they worsen during menstruation. A pelvic exam may also be performed to check for any abnormalities.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests, such as transvaginal sonography (TVS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are commonly used to identify and characterize endometriosis lesions.

TVS is a first-line imaging technique providing detailed dynamic images of the pelvis with minimal patient discomfort. It helps identify all of the bowel’s layers and any potential endometriosis nodules.

MRI, on the other hand, is typically used as a second-line diagnostic tool. It excels in evaluating the extent of the disease and identifying any specific organ involvement and depth of infiltration.

Endoscopy and Biopsy

An endoscopy may also be performed to examine the bowel for any abnormalities. A biopsy can be taken during this procedure to check for the presence of endometriosis cells. However, this method has its limitations as it only provides a superficial sample, and endometriosis usually involves deeper layers of the bowel wall.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis. This surgical procedure allows for visual inspection of the peritoneal cavity and can provide a definitive diagnosis. The surgeon can also assess the extent of the disease and its impact on other organs.

Misdiagnosis of Bowel Endometriosis

Bowel endometriosis is often misdiagnosed due to its similar symptoms to other gastrointestinal disorders. This condition is frequently mistaken for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease, and even colon cancer.

It’s crucial for healthcare providers to consider a possible diagnosis of bowel endometriosis in women presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms, especially if these symptoms worsen around the menstrual cycle.

Treatment of Bowel Endometriosis

Treating bowel endometriosis is typically multidisciplinary, involving a team of specialists. It generally involves a combination of medical and surgical therapies.

Medical Therapy

Medical treatments aim to control the symptoms of bowel endometriosis and may include pain relievers, hormonal therapies like oral contraceptives or progestins, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs. These treatments work by reducing inflammation and suppressing the growth of endometrial tissue.

Surgical Therapy

In more severe cases, or when medical therapy is ineffective, surgery may be necessary. The type of surgery will depend on the extent and location of the endometriosis. In some cases, a conservative approach may be used, where the surgeon attempts to remove the endometriosis while preserving as much of the bowel as possible. In other cases, a segment of the bowel may need to be removed.

Laparoscopic Surgery

Laparoscopic surgery is often the preferred method for treating bowel endometriosis. This minimally invasive procedure allows for precise removal of the endometriosis with less damage to surrounding tissue and quicker recovery times. However, it requires a skilled surgeon and may only be an option in some cases.

Read More: Why It’s Important Your OB-GYN Specializes in Endometriosis?

Bowel Endometriosis and Fertility

Research indicates that bowel endometriosis may have an impact on a woman’s fertility. This could be due to the inflammation and scarring caused by the disease, which can interfere with the normal function of the reproductive organs.

In cases where infertility is an issue, assisted reproductive technologies may be considered. However, surgery to remove the endometriosis is often recommended first to increase the chances of a successful pregnancy.

Read More: Does Endometriosis Cause Infertility?

Conclusion

Bowel endometriosis is a complex condition that can significantly impact a woman’s quality of life and fertility. Early diagnosis and effective treatment are crucial to managing this condition and minimizing its effects. Suppose you’re experiencing symptoms of bowel endometriosis. In that case, it’s important to consult with a healthcare provider who is knowledgeable about this condition and can guide you through the diagnosis and treatment process.

References:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6996110/

https://drseckin.com/bowel-endometriosis/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6397811/

Through the Looking Glass: Reflecting on 2023

Embarking on the journey of self-reflection is not just a personal endeavor; for us at iCareBetter, it’s a collective celebration of progress, community, and collaboration. As we bid farewell to 2023, a year marked by challenges and triumphs, it’s time to take a look into the past year and reflect on all that has been accomplished. Join us as we navigate through the areas of growth, community involvement, projects, and meaningful collaborations that shaped our year. In this special blog post, we’re excited to share the insights gained from our podcast endeavors and offer a sneak peek into the thrilling developments that await us in 2024. Let’s rewind, recap, and anticipate the exciting narrative that continues to unfold in the ever-evolving story of iCareBetter.

About iCareBetter

iCareBetter is an innovative platform dedicated to helping patients with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain find compassionate and skilled experts. All experts on iCareBetter have shown knowledge and expertise in the treatment of endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain.

Vision

Our vision is to reduce the symptom-to-effective treatment of endometriosis to less than a year. Studies show that patients with endometriosis spend an average of 7.5 years to have an official diagnosis. Moreover, even after the diagnosis, patients will have to spend several years with multiple failed treatment attempts. After the long delays in diagnosis and treatment, they might be lucky enough to receive effective treatment from an expert.

Mission

Our mission is to improve access to high-quality specialized care for those with endometriosis. iCareBetter wants to combat the issue of patients living in confusion, pain, and isolation. To that end, we hope to connect as many patients to the right experts as early as possible. And we hope that this will ensure timely diagnosis and effective treatment.

To read more about why iCareBetter was built and the inspiration behind it, check out our blog here and listen to episode 1 of the podcast here, where Saeid and Jandra give you a behind the scenes look into what inspired them.

What happened in 2023?

In 2023, iCareBetter grew in many ways, including new avenues to provide education along with collaboration from the community. Here are some of the highlights!

- We started a podcast! iCareBetter: Endometriosis Unplugged is hosted by Jandra Mueller, DPT, MS a pelvic floor physical therapist and endometriosis patient. The podcast is available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Youtube.

- We had 19 weekly episodes in season one

- Listeners joined from all over the world, reaching 22 countries

- We brought on a team to help with new content on social media creating a more visually appealing platform, community engagement, and followers.

- We now have 211 providers on our website available and ready to help those suffering from endometriosis and we are continuing to grow!

- Our blog content is now consistent with twice weekly posts bringing you updates on all things endometriosis.

What To Expect in 2024

While 2023 was a big year for iCareBetter, we hope to continue the growth and expand our providers across the globe. Our hope is to increase our collaboration with medical specialists, researchers, and advocates. There are some exciting things to come in 2024 including a new season of iCareBetter: Endometriosis Unplugged as well as some other projects that will be announced in 2024.

We hope you have found our resources helpful either for yourself or a loved one, and hope you continue to share the love and spread the word about Endometriosis. All of us here at iCareBetter wish you a safe and happy new year.

Cheers to 2024!

Do you or a loved one have Endometriosis? Here are some blogs that may help you get started on your journey.

- Endometriosis Signs and Symptoms: Everything You Need to Know

- Endometriosis Facts & Myths: Dispelling the Misconceptions

Women’s Health Research and the White House Initiative

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays! It’s time for some good news when it comes to researching ‘women’s diseases.’

Women’s health has long been an area that has been overlooked and understudied in medical research. Despite making up more than half of the population, women have historically been underrepresented in clinical trials and medical studies, leading to significant gaps in knowledge and understanding of women’s health issues. However, recent developments, such as the establishment of the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, are changing the landscape and paving the way for a new era of research and innovation in women’s health.

Table of contents

The Historical Underrepresentation of Women in Research

For decades, women’s health needs were considered a low priority in the scientific and medical fields. During the 1970s, when the women’s health movement emerged as part of the larger women’s movement, it became apparent that women were significantly underrepresented in medical and scientific research. At that time, there were few women working in medicine and science, and the lack of representation had serious implications for the understanding and treatment of women’s health conditions.

One significant example of the cautious approach towards including women in research was the Food and Drug Administration’s policy in 1977, which recommended excluding women of childbearing potential from early-stage drug trials. This policy was a response to the tragic consequences of the drug thalidomide, which caused severe birth defects in thousands of babies born to women who had taken the drug during pregnancy. While the intention was to protect women from potential harm, it resulted in a lack of data on how drugs specifically affected women.

The Shift Towards Inclusion and Advocacy

As awareness grew about the exclusion of women from research studies, advocacy groups and activists began to protest for change. They argued that individual women should be allowed to make informed decisions about participating in research and that excluding women limited their access to potentially life-saving treatments. The Public Health Service Task Force on Women’s Health Issues, in their 1985 report, called for long-term research on how behavior, biology, and social factors affect women’s health, further highlighting the need for inclusion.

In response to these concerns, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established a policy in 1986 that encouraged the inclusion of women in studies. This policy, published in the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts in 1987, urged researchers to include women and minorities in their studies and provided guidelines for doing so. The policy was further reinforced in 1989 when NIH announced that research solicitations should prioritize the inclusion of women and minorities.

The Founding of the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research

In 1990, the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues requested an investigation into NIH’s implementation of guidelines for the inclusion of women in research studies. The subsequent report by the General Accounting Office (now known as the Government Accountability Office) highlighted inconsistencies in applying the inclusion policy and the need for improved communication. As a result, the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) was established in 1991 to monitor and promote the inclusion of women in research.

Under the leadership of Dr. Bernadine Healy, the first female NIH Director, the Women’s Health Initiative was launched in 1991. This initiative consisted of clinical trials and an observational study involving over 150,000 postmenopausal women. The trials aimed to investigate the effects of hormone therapy but was stopped due to incorrect interpretation of the data resulting in the majority of women stopping their hormone therapy overnight, literally. We are still dealing with the consequences of this today.

Legislation and Policies to Ensure Inclusion

While the inclusion of women in research was initially an NIH policy, it became federal law in 1993 through the NIH Revitalization Act. This act included provisions requiring the inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research funded by NIH. The law mandated that NIH ensure the inclusion of women and minorities and that trials be designed to analyze whether variables affect women and minorities differently. It also emphasized that cost should not be a reason for exclusion and called for outreach efforts to recruit diverse populations for clinical studies.

Since the establishment of the ORWH, the office has monitored adherence to inclusion policies and guidelines. Researchers receiving NIH funding are required to report on the sex, race, and ethnicity of participants enrolled in clinical trials. These reports contribute to the ongoing efforts to promote inclusivity and address health disparities among different populations.

Improving Women’s Health Through Research

The White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, announced by President Biden and led by First Lady Jill Biden, signifies a renewed commitment to advancing women’s health research. The initiative aims to galvanize the federal government, private sector, and philanthropic communities to close research gaps, address health disparities, and pioneer the next generation of discoveries in women’s health.

Under this initiative, concrete recommendations will be delivered to the Biden-Harris Administration within 45 days, outlining actions to improve research on women’s health and maximize investments in this field. Priority areas of focus will be identified to ensure transformative outcomes, ranging from heart attacks in women to menopause and beyond. The initiative also seeks to engage stakeholders from the scientific, private sector, and philanthropic communities to drive innovation and foster collaborative partnerships.

By prioritizing research on women’s health, we can gain a deeper understanding of conditions and diseases that predominantly affect women, such as endometriosis, cardiovascular disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. This knowledge will enable healthcare providers to better prevent, diagnose, and treat these conditions, ultimately improving the lives of millions of women.

The establishment of the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research and the ongoing efforts to promote inclusion in medical research mark significant milestones in addressing the historical underrepresentation of women in studies. Through policies and legislation, initiatives like the Women’s Health Initiative, and the monitoring of adherence to inclusion guidelines, progress is being made to close research gaps and improve women’s health outcomes.

Research plays a crucial role in understanding the unique aspects of women’s health and developing effective treatments and interventions. By prioritizing and investing in research on women’s health, we can empower women, healthcare providers, and researchers to make informed decisions and advancements that will positively impact the health and well-being of women across the nation. The White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research is a vital step towards achieving this goal and creating a future where women’s health is fully understood, supported, and prioritized.

What you can do!

The Initiative is accepting written comments and input, we urge everyone to get involved.

You can send in either a word document or PDF file to WomensHealthResearch@who.eop.gov

Related reading:

- Endometriosis Signs and Symptoms: Everything You Need to Know

- Endometriosis Facts & Myths: Dispelling the Misconceptions

- Why was iCareBetter built?

References:

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/11/13/fact-sheet-president-joe-biden-to-announce-first-ever-white-house-initiative-on-womens-health-research-an-effort-led-by-first-lady-jill-biden-and-the-white-house-gender-policy-council/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/gpc/briefing-room/2023/11/17/launch-of-white-house-initiative-on-womens-health-research/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/11/13/remarks-by-president-biden-and-first-lady-jill-biden-establishing-the-first-ever-white-house-initiative-on-womens-health-research/

- https://orwh.od.nih.gov/toolkit/recruitment/history#:~:text=Inclusion%20Becomes%20Law&text=In%201993%2C%20Congress%20wrote%20the,as%20Subjects%20in%20Clinical%20Research.

Endometriosis: Is it a Disability?

Endometriosis, a debilitating condition affecting millions of women globally, often prompts questions about its influence on daily life and work ability. This article provides an in-depth analysis of endometriosis, how it affects women’s work ability, and the possibility of qualifying for disability benefits.

Endometriosis is a medical condition that primarily affects women during their reproductive years, and is very prevalent, with over 80 million women diagnosed worldwide, typically between the ages of 20 and 40. Treatments such as surgery and medical management as well as physical therapy can alleviate some symptoms, but there is currently no definitive cure for the disease.

Table of contents

Endometriosis and Disability: An Intricate Relationship

The symptoms of endometriosis vary greatly among individuals. The most common symptom is pelvic pain, particularly during menstruation, sexual intercourse, bowel movements, or urination. Other symptoms include abdominal bloating, nausea, as well as infertility, among other symptoms.

Endometriosis can significantly disrupt daily functioning due to associated symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and psychological distress especially during one’s menses (period) but is not always confined to that time of the month. Consequently, the disease might qualify as a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in certain cases. However, it is important to know that the Social Security Administration (SSA) does not automatically classify endometriosis as a disability in endometriosis disability act.

Endometriosis and Social Security Disability Benefits

Qualifying for Social Security disability benefits due to endometriosis is not straightforward. The SSA considers two primary factors when determining if an individual qualifies for SSDI (Social Security disability insurance) or SSI (Supplemental Security Income) disability benefits:

1. Does the individual’s condition meet (or equal) the requirements of a listed impairment?

2. If not, do the symptoms of endometriosis significantly interfere with the individual’s ability to function, to the point where they cannot perform any type of job safely?

Since endometriosis is not listed as a qualifying condition, sufferers cannot automatically meet the first criterion. However, they might still qualify for Social Security disability if their symptoms significantly impede their ability to work, what the SSA calls “substantial gainful activity,” or SGA.

How to Qualify for Social Security Disability for Endometriosis

To qualify for Social Security disability due to endometriosis, it must be demonstrated that the symptoms of the disease prevent the afflicted individual from performing their job. The SSA will then assess if there is any type of job that the individual can safely perform. This evaluation considers medical records, age, work experience and job skills, education, and residual functional capacity (the minimum work that can be expected from an individual).

Applying for Social Security Disability for Endometriosis

Applications for Social Security disability benefits can be made online, through a phone call to the Social Security’s national office, or in person at a local Social Security field office. Winning a disability claim for endometriosis can be challenging, but applicants can seek assistance from an experienced disability attorney or non-attorney representative.

Endometriosis and Employment: A Complex Scenario

While endometriosis can significantly impact an individual’s ability to work, it does not automatically lead to unemployment or early retirement. In fact, many women suffering from endometriosis are able to maintain their employment status, albeit with certain adjustments to accommodate their symptoms.

Work Ability and Endometriosis

A woman’s ability to work can be severely compromised by endometriosis, with the disease often linked to poor work ability at age 46. This decreased work ability can lead to increased absence from work due to health issues. However, despite the increased absenteeism, women with endometriosis often maintain an employment rate comparable to women without the disease. It makes you question why?

Over the past few years, emphasis has been put on staying home if you are sick, as a safety measure for spreading disease, though many with endometriosis may not be able to afford days off of work either because financially they are unable, or there is worry about saying PTO for an unexpected turn of event such as a necessary surgery, or increased symptoms causing debilitating pain. So we suffer through expecting there to be worse days. Women in general, tend to minimize their own symptoms or question if they are “really that bad” as a result of societal influences.

Endometriosis Disability Act and Retirement

The emergence of disability retirement due to endometriosis is not common. Despite the debilitating symptoms of the disease, the risk of early retirement is not significantly higher for women with endometriosis compared to those without the condition. This finding is encouraging and demonstrates the resilience and determination of women battling this condition. Or, is it that those with endometriosis stay working longer because of the financial need and medical bills?

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a complex and debilitating condition that can significantly impact a woman’s ability to work. However, it does not inevitably lead to unemployment or early retirement per the literature, though that does not mean that those living with the condition are able to work feeling well or without worry about consequences of not working. With appropriate medical treatment and workplace accommodations, we hope that not only can those with endometriosis keep working, but with a higher quality of life while working.

References:

- The Americans with Disabilities Act www.ada.gov

- Rossi, H., Uimari, O., Arffman, R., Vaaramo, E., Kujanpää, L., Ala‐Mursula, L., Piltonen, T.T., 2021. The association of endometriosis with work ability and work life participation in late forties and lifelong disability retirement up till age 52: A Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 100, 1822–1829.

“You Don’t Have Endometriosis” My Story

Many people have been asking about the return of our podcast iCarebetter: Endometriosis Unplugged. We are on a hiatus but thought it may be nice to share some success stories as those were quite popular. As we get the podcast up and running again and more interviews underway, I thought it might be helpful to share my own story, and why I am such an excision surgery advocate, though I understand it does not address everything. When you are told “you don’t have endo” you have two choices – give up and look elsewhere or keep pushing.

Many of us keep pushing and get pushback about having central sensitization, needing mental health help, or it’s just not the right diet and supplements. Yes, all of those things may be true AND it also may be true that you didn’t have the correct surgery or surgeon.

Table of contents

Endometriosis Symptoms

I was twenty-eight years old when I suddenly started feeling a sharp pain in my lower abdomen, one that was all too familiar in my teen years. I was told by the emergency room doctor shortly after starting my period that the pain I was having was likely due to rupturing cysts, and told my mom I needed to see a gynecologist to talk about birth control options to prevent them from happening. I was thirteen years old at the time, in the emergency room after my mom and brother had to pull me out of the shower because I experienced sudden and severe abdominal pain causing me to not be able to stand up or walk.

This was 15 years later but all too familiar. I saw my doctor who recommended an ultrasound and was told once again “it was probably a ruptured cyst,” and that I may want to consider birth control pills in addition to my Mirena IUD as it “could be defective,” despite no periods or pregnancy scares over the last two and a half years since I had it replaced. At the same time, I became severely constipated and bloated with anything I ate, as well as feelings of sharp rectal pains and an odd sensation throughout my body, like a tingling or wave of lightheadedness during times I did have an urge to have a bowel movement. This also was very familiar to me but I hadn’t had it in years, it was less like a pain but a very intense uneasiness that made me stop in my tracks and literally pray to God for it to end, which it did, usually within a minute or two.

After the ultrasound, the addition of Lo Loestrin along with the Mirena IUD, next step was a colonoscopy with no answers except for some relief after three months of barely any movement, and a diagnosis of IBS (irritable bowel syndrome). At this point, I had seen my OBGYN, a GI specialist, a naturopath, and discussed with my PT colleagues, but still no answers.

I should mention, this all started after the most severe stress I had ever experienced at this point – a divorce. So it was no surprise that throughout all of these visits, it was definitely suggested that this could all be due to stress and anxiety. I knew there was more though, and I was seeking out the help I needed to learn to handle the stressors.

Trials and Tribulations

After about two years of trying various diets, food allergy & sensitivity testing, changes in birth control pills, a new GI doctor finally asked if I’d ever been tested for SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth). “SIBO? What’s that?” I responded. Sure enough SIBO was in fact part of the problem (both hydrogen and methane positive) and after two rounds of antibiotics, things started to feel somewhat normal, until the UTI-like symptoms began. However, it was not a UTI, I learned that I was experiencing side effects from the birth control pill I had started to control the pain from the cyst ruptures, also known as hormonally mediated vestibulodynia, which we recently wrote about in a previous blog which you can read here.

At this point, constipation was still a struggle, but nothing like it was before, the antibiotics helped, the diets helped, everything helped a bit, until it didn’t. The rectal symptoms were recurring, the constipation still a daily struggle and if I had a “bad” diet day, it took almost a week to get back on track. SIBO was recurring, the diets were stressful, the symptoms would fluctuate without a rhyme or reason and then the severe abdominal pain came once again along with a fever and nausea. It was time to go back to the ER.

The ER Visit

This felt all too familiar, I waited several hours and even overheard the team in triage say “bladder symptoms, probably UTI.” I was finally rolled in and waiting for a CT scan to check for appendicitis. The pain was severe and the only thing that made a dent, and in my fever, was the lovely little morphine button. As soon as it got close to the time to press the button again, fever would spike and pain would come back.

Good news and bad news. Good news no appendicitis, bad news is in the scan they saw a cyst on my liver and I need more imaging. More imaging was done and they couldn’t say what the cyst was, but this time they saw that I had some swelling in my lung and there was something called ‘atelectasis’ or a partial deflation of my lung. They finally sent me for a pelvic ultrasound and guess what the conclusion was “you probably ruptured a cyst, we see fluid behind your uterus. Have you seen your gynecologist?”

At this point the fever wasn’t breaking, I had no answers but 10 more problems on the list and they admitted me to hospital where I stayed for four days.

The Hospital Stay

I was checked by probably every type of specialist within those four days. Hospitalist, GI doc, urologist, immunologist, obgyn, and even infections disease. I had breakouts in hives and rashes because I am very sensitive to most antibiotics, I was in and out of imaging machines, my oxygen levels wouldn’t stay up – likely because of the partial lung collapse, and I had to practice breathing into that plastic thingy (an inspirometer), and on top of it, they diagnosed me with a heart murmur and was told I needed to follow up with a cardiologist for a further workup.

In the end, they released me because the fever finally broke and my pain subsided and told me “we have no idea, it was probably some virus, follow up with your OBGYN.”

The OBGYN (Urogynecologist)

It was after a patient of mine, who had endometriosis, asked me “Do you think you could have endo?” I really never thought about it, my younger sister had endo or was clinically diagnosed with it many many years prior, but I didn’t feel like she did, she had severe period pain, would miss work and school, heavy bleeding, all the endo symptoms and I had GI issues and intermittent severe abdominal pain from rupturing cysts.

At my appointment, I brought up this question – “how do they KNOW I ruptured a cyst, if it ruptured? She told me that because of the fluid and the symptoms, it was likely that, and that we should see the fluid go away shortly as the body reabsorbs it. I still had my IUD so I wasn’t sure when I was ovulating and she agreed to do weekly transvaginal ultrasounds to monitor. The fluid never went away.

I had a lovely doctor, and she really helped me get on the right path, though she was not an endometriosis specialist, she was able to take me to surgery. I knew what she could and couldn’t do, and she was very transparent with me about this. By this time, I had done more research and knew there was a very high likelihood I would have to have another surgery – an excision surgery. I was okay with that because I knew what I was going into and knew what the outcomes could be, and it was essentially free, because of that lovely ER visit hitting all of my deductibles and out of pocket maximums.

Surgery #1 (November 2017)

To keep it short, I was told I didn’t have endo. Despite this, she said that my left uterosacral ligament was ‘very strange’ and she took a biopsy and a sample of the pelvic fluid that never went away. When I got my pathology report back it read:

- Left Uterosacral Ligament: Fibrotic inflammatory tissue

- Pelvic Free Fluid: Cells consistent with endometriosis

I was still not given an endometriosis diagnosis after this, and I felt horrible. This was November 2017 and all the tools I had been able to use to manage to some degree, didn’t work. I was so fatigued, my GI symptoms were awful, SIBO came back yet again, and just felt unwell. Everything was difficult but at least I was on the right track.

Surgery #2 (March 2018)

After having my surgical pictures reviewed by trusted colleagues, and the most painful, but helpful pelvic exam that literally reproduced my symptoms. My doctor told me “this is endometriosis, I can feel nodules.” She assured me that it presents in different ways, and really taught me the difference between the training of endometriosis specialists vs the standard gynecologist. She educated me about the different types of lesions and that not all of them come back as endometriosis because they lack “stroma and glands” but that fibrotic endo is likely what I had, and it can cause problems. This made a lot of sense and in March 2018, I had my second surgery, but this time it was the right one. My pathology report looked quite a bit different this round, and I felt entirely different.

- Uterus: globular and soft (possibly adenomyosis)

- Rectovaginal septum: Peritonealized fibrofatty with focal reactive mesothelial hyperplasia

- Right Uterosacral Ligament: Peritonealized fibromuscular and fatty tissue

- Left Uterosacral Ligament: Fibromuscular and fatty tissue with few CD10 positive cells compatible with endometriosis

- L peritoneum (pelvic sidewall): Fibrofatty tissue with endometriosis with single non-necrotizing granuloma

It was definitely validating seeing this report but it was even better when it just was gone, the inflammation, the pain, much of what I was experiencing was just gone. I now understood what many of my patients had told me. While this is not everyone’s experience, in my personal and professional experience, when you’ve addressed all the various factors, oftentimes the lesions are the last one and there is a vast difference in those who have a true excision surgery versus an incomplete excision surgery or non-excision surgery. Dr. Vasilev just wrote about how to find a specialist and some considerations.

If you suspect endo is your problem, and you’ve had a surgery though you suspect it may not have been a thorough one, I sincerely urge you to seek a second opinion. I see this all too often, and it saddens me. I understand, because I have been there. The instances I see this the most are the ones who have fibrotic endo and are either told “you don’t have endo” or it’s never even addressed during their surgery because it is not recognized as endo by many doctors.

The years following…

I did well for about three years, and after a very significant reaction I had, and months of inflammation following, I felt those endo symptoms creep back. The constipation that just felt like something was blocking my intestines from moving and the rectal symptoms, which is called dyschezia, and is one of the clinical manifestations of endometriosis. I had some symptoms that concerned me about thoracic endo, and the other new symptom was that I was getting fevers and flu-like symptoms about 1-2 days before my period that would dissipate on day 3 of my cycle. Because of COVID, and working in healthcare, I was testing frequently, but it was never covid and it would never be more than 48-36 hours.

I found a wonderful in-network doctor in San Diego, and in February 2022, I had my third surgery (second excision) and there was regrowth of only fibrotic tissue in the rectovaginal septum as well as adhesions attaching my sigmoid colon to the left pelvic side wall. Once again, my symptoms completely resolved following the surgery.

My story is not a unique one, but I felt it was important to share as I have had this same discussion with others in urging them for a second opinion and sure enough, they DID have endo, they just weren’t listened to, or hadn’t found the right doctor. I get discouraged when I hear people dismiss excision surgery because of the lack of good studies supporting it. The surgery is not the issue, the research is the issue. However, surgery won’t fix or cure all of the issues one may have and while the surgery (I feel) is crucial to most, if not all, people; you still need to be a detective and address ALL of the issues and root problems for the best outcome.

Check out our podcast iCarebetter: Endometriosis Unplugged, available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts for more personal stories and discussions with experts, and we will see you for more episodes in 2024!

Related reading:

- Endometriosis and Painful Intercourse: Is it Really Just Endometriosis?

- Finding an Excision Specialist: What you Need to Know

- All You Need to Know About Endometriosis Lesions

Understanding Neuroproliferative Vestibulodynia and the Connection with Endometriosis

Table of contents

A few weeks ago, we delved into the intricacies of vestibulodynia and its potential association with painful intercourse in individuals with endometriosis. We presented an overview of vestibulodynia subtypes in general and discussed one of the more common presentations we see in those with endometriosis – hormonally mediated vestibulodynia which in many is caused from the side effects of the birth control pill, which are offered as first line “treatments” for endometriosis. Today, we will focus on another subtype, neuroproliferative vestibulodynia (NPV), and the fascinating connections are are seeing in these two conditions, including the role of mast cells.

If you missed our previous discussion on painful sex and vestibulodynia, you can find the detailed information here.

Recent research endeavors have yielded valuable insights into the fundamental causes of these conditions, unveiling a shared mechanism involving neuroproliferation, characterized by an increase in nerve cells. Furthermore, an elevated presence of mast cells—integral components in immune function—has been observed both in endometriosis tissue and the vestibule of individuals diagnosed with neuroproliferative vestibulodynia (NPV).

Individuals diagnosed with NPV undergo a surgical procedure which is excised to remove the problematic tissue, sound familiar?

This surgical approach has demonstrated notable success in alleviating pain for individuals affected by NPV. Dr. Paul Yong, an OBGYN, endometriosis surgeon, and researcher based in Canada, addressed the parallels between these two conditions during his presentation titled ‘Neuroproliferative Dyspareunia’ at the ISSWSH’s annual conference in March 2022. Dr. Yong’s insights laid the foundation for subsequent research, with Dr. Irwin Goldstein initiated further exploration earlier this year. We were lucky enough to be able to speak directly with these two on our podcast iCarebetter: Endometriosis Unplugged, available on Spotify (linked here) and Apple Podcasts.

A Quick Overview

Vestibulodynia

Vestibulodynia is a condition characterized by pain in the vestibule, the area of tissue within the vulva that surrounds the opening of the vagina. This pain can be described as sharp, stinging, burning, or hypersensitive, and can occur spontaneously or be provoked by touch or pressure, and many people will report superficial dyspareunia (or pain upon insertion) which is not limited to penis in vagina sex. Vestibulodynia is a subcategory of a broader condition called vulvodynia, which refers to chronic pain in the vulva.

Endometriosis

On the other hand, endometriosis is a condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus, often causing pain and fertility issues. This condition can cause deep dyspareunia, or pain with deep vaginal penetration. Like vestibulodynia, the pain associated with endometriosis can be chronic and can significantly impact the quality of life.

The Concept of Neuroproliferative Dyspareunia

Both vestibulodynia and endometriosis can lead to pain during sexual intercourse and the term neuroproliferative dyspareunia, is in reference to the source of the pain. Both tissues have been shown to have neuroproliferation, or increased growth, of nerve endings in the areas affected by these conditions and we are now seeing an aberrant amount of mast cells as well also contributing to inflammation. This overgrowth of nerves, and presence of excessive mast cells, can lead to heightened sensitivity and pain during vaginal penetration, both superficially, as well as deep.

Neuroproliferation in Vestibulodynia

In the case of vestibulodynia, research has shown that there are too many nerve endings in the vestibule tissue. This overgrowth of nerves, or neuroproliferation, is still under investigation. However, it is believed that this could be due to a congenital birth defect, with the excess nerve endings developing very early. There are two types of neuroproliferative vestibulodynia: primary (congenital) and secondary (acquired). In primary vestibulodynia, individuals have experienced pain their entire lives though usually identified shortly after menses or with first attempts at penetration (sex, tampons, speculum exams) while in secondary or acquired vestibulodynia, pain develops later in life usually after an event such as an allergic reaction, chronic yeast infections or other infection, and there has typically been a period of normalcy prior to these event.

Neuroproliferation in Endometriosis

In endometriosis, nerve fibers have been found around endometriosis lesions in the pelvic peritoneum. These nerve fibers are more numerous in individuals with endometriosis compared to those without the condition. The increase in nerve fibers is believed to be driven by the immune response to infection or allergy, leading to nerve proliferation.

Symptoms of Neuroproliferative Vestibulodynia and Endometriosis

Vestibulodynia Symptoms

People with vestibulodynia typically experience pain at the entrance of the vagina, called the vestibule. This pain can be described in various ways, including as sharp, stinging, burning, or hypersensitive. This pain can also be classified by when it occurs, with provoked vestibulodynia referring to pain that occurs with touch or pressure, while unprovoked pain occurs spontaneously.

Endometriosis Symptoms

In endometriosis, the pain is typically experienced deeper within the pelvis, often during or after sexual intercourse. This deep dyspareunia can also be accompanied by other symptoms, such as painful periods (dysmenorrhea), painful bowel movements, and chronic pelvic pain to name a few.